At the Leh airbase in Jammu and Kashmir, located at a height of 11,000 feet, where even breathing requires a big effort, everybody seemed to be in a hurry. Wing Commander S. Ramesh, commanding officer of the Indian Air Force's elite Siachen Pioneers based in Leh, wanted his three Cheetal helicopters and the lone Russian-made Mi-17V5 chopper to take off at first light to the Siachen Glacier, the world's highest battlefield.

The helicopters are among the most essential things for survival in Siachen where India continues its 32-year-old Operation Meghdoot to ward off Pakistan's attempts to capture the heights. “There are three musts for surviving in the treacherous terrain and weather in Siachen,” said Squadron Leader V. Chauhan, a Cheetal pilot. “The first is a doctor, who takes care of the health of the men. Then come the porters, who supply rations and carry loads for the troops, and most importantly, the helicopter, which brings rations and evacuates the sick from the 78km-long glacier,” he said.

In winters, when people enjoy an extra hour of sleep, an air warrior has to wake up at least two hours before normal time. For the helicopter to take off at 6am, the pilot has to be up by 4:30am. And the technical crew needs to be ready by 3:30am.

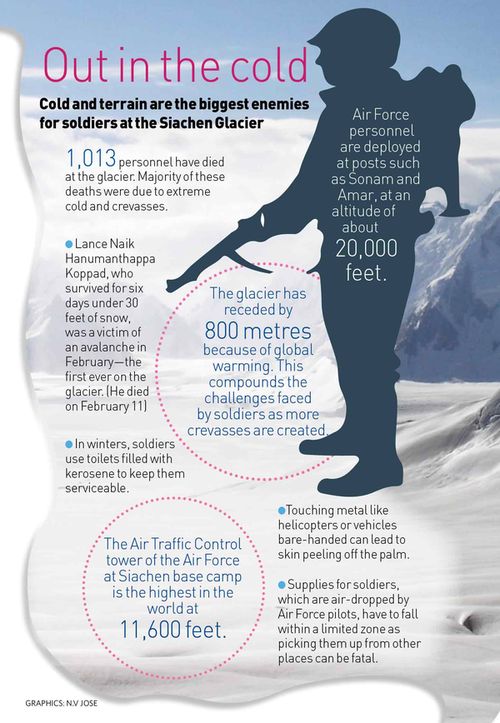

“This is a routine we have to follow throughout the year irrespective of whether the temperature is 3 degrees Celsius or -30 degrees Celsius. We have to reach the soldiers waiting for fresh supplies in the higher reaches. It is this spirit that keeps us awake,” said Ramesh. “Keeping the machines ready at all times is a difficult thing to achieve, especially in winters,” he said. “One has to be careful not to touch the machinery bare-handed since it would mean losing the skin on the palms as it may get stuck on the ice-cold metal objects,” said Warrant Officer R.K. Tripathi.

In the last 32 years, operations in Siachen have evolved in a big way. Electric power was once a luxury in the region, but now, diesel generators light up entire townships and let soldiers use basic comforts like immersion rods and electric room-heaters. “Such things were a luxury in the early days as kerosene-lit bukharis would provide us comfort from the deadly cold. A station commander at Thoise died after his hut caught fire probably from the bukhari,” said Group Captain Sandeep Mehta.

The helicopter fleet, too, is undergoing an upgrade. Cheetahs, the old warhorses, are being replaced by Cheetal helicopters. The new choppers, powered by a stronger engine, let pilots carry out more sorties even beyond the 18,380-foot-high Khardungla pass. “Earlier, the machines could not take off from the glacier, but with the new choppers, that is not an issue. The operations can be carried out during the entire day till lights permit,” said Ramesh.

The operations are dictated mostly by the weather and we got a first-hand experience of it while waiting for our flight from the Siachen base camp to the Benazir post at a height of around 17,000 feet. From a Russian-origin truck at the base camp, which is the world's highest air traffic control tower, Ramesh and his deputy, Wing Commander Anshul Saxena, kept checking the weather updates from posts which are at a height of around 19,000 feet. From 11am, cloud formations could be seen over the higher posts, making it difficult for the choppers to fly.

The cloud formations played hide-and-seek and it seemed the flight over the glacier would be difficult, but the pilots remained hopeful. Finally, by 4pm, when everyone other than the pilots was mentally prepared to go back to Leh, came the good news that the choppers could fly up to forward posts at 16,000 feet.

Our Mi-17V5 flown by Squadron Leader Mayank Paliwal had four drums of 1,000kg kerosene, tied to a parachute, which were to be delivered at camp 5. The rear of the chopper was kept open so that the passengers could take in oxygen at regular intervals. At the posts, one could see men in their tents built of parachute clothing, imported from Russia, waiting with oxygen bottles close by. The air at such high altitudes contains only 50 per cent oxygen and without bottled oxygen, one could suffer from acute mountain sickness as was experienced by a flight mate.

As we flew from the base camp watching the Nubra river turning into a thick layer of ice, we took several turns before the pilot saw a wall of clouds over the glacier area. We then took a U-turn and dropped the load at a post.

As we returned to the helipad at the base camp, men from the Army's 18th Grenadiers checked whether a load could be dropped at the desired camps. “We will do that tomorrow as the weather is bad,” replied Paliwal. “We have to remain positive and even if we get a small window, we fly. But even in that josh (enthusiasm), flight safety is the most important thing for us,” he said.

With weather conditions deteriorating at Khardungla, it was difficult to return to Leh. We were forced to take a right turn from the Y junction where the Nubra, flowing down from the Siachen Glacier, meets the Shyok and land at Thoise, the northernmost airbase of the country, making it clear that weather remains the most important factor for any operation in Siachen.

In terms of facilities and equipment, a lot has changed, but even today, the basic requirements to fight the freezing winters remain the same. For instance, answering the call of nature in a commode filled with kerosene oil and flushing it down again with kerosene is perfectly normal for someone in Siachen. “Here, it is routine. If you don't use kerosene in toilets in the winter, forget about using the toilet for the entire season. Or else, you will have to spend your entire day heating the sewage pipe by burning it and dousing the fire in order to defreeze it,” said Group Captain Sandeep Mehta, who served in the Siachen Glacier in the late 1980s.

Keeping yourself warm is another big challenge. In winters, when the temperatures dip below minus 15 degrees Celsius even during the day, pilots who land at the glacier with their cockpit doors open wear shoes which are two sizes bigger. “The first layer includes glycerine over which newspapers are rolled in, followed by thick woollen socks. Then we put on giant shoes to keep our feet warm,” said Chauhan.

The Defence Research and Development Organisation has been working towards keeping the soldiers warm with battery-heated gloves and socks for longer hours—the batteries drain out in 30 to 40 minutes in severe winter. It has forced the soldiers to rely on the time-tested multilayered clothing formula.

New challenges also keep coming up. “Early this year, we experienced an ice avalanche for the first time in which Lance Naik Hanumanthappa Koppad sacrificed his life along with nine other soldiers,” said Lieutenant Colonel S. Sengupta, commandant and chief instructor of the Siachen Battle School. He said it was an avalanche of hard ice, unlike the snow avalanches of the past. Sengupta said climate change, which had resulted in rising temperatures, was leading to the creation of a lot of crevasses, one of the biggest enemies of the soldiers serving in Siachen. Most of the 1,013 soldiers who died here have been victims of adverse weather rather than enemy attacks.

Reminding us of the vagaries of weather, there was an unexpected bout of rainfall at the base camp, a rare event at such heights. “Vegetation at heights above 12,000 feet was unknown so far, but now we see greenery even at 15,000 feet and in summers, these heights don't even look like the glacier that we have known,” said Saxena.

Sengupta said the soldiers now carried avalanche buoyancy bags which would help them float over snow during avalanches. The defence ministry has also imported, in large numbers, Xaver barrier-piercing radars that can find human beings trapped as deep as 20 metres. It was such technology that helped the rescuers reach Hanumanthappa and his comrades within three days of the avalanche. Ramesh and his men were the first ones to respond to the avalanche as they flew 26 sorties on the first day and nearly 130 in next four days, ignoring unfavourable weather.

For soldiers deployed on higher altitudes like the Siachen Glacier, global warming is likely to throw up more challenges. However, looking at Sengupta's men jogging and climbing the icy cliffs and Ramesh's boys in their machines, it seems there is no mountain too high and no valley too deep for them. More than any sophisticated equipment, the spirt of these men is what matters as they strive hard to keep the tricolour flying atop the world's largest glacier outside the poles.