For 24-year-old IT professional Indhuja Pillai or IP, as she likes to be called, life took a dramatic turn after college. This Bengaluru resident, who considers herself a loner, cut her hair short, got a tattoo and started making solo trips on her Bullet. Soon, parents started pestering her to get married, and posted her details on a matrimonial site, mentioning the usual traits people look for in a potential partner. “People look at me and get the impression of a 'boyish' girl,” says Pillai. “I can't cook either. Hence with all this, I don't fit the bill.”

But as a “big fan of love and marriage”, Pillai posted a matrimonial CV of herself on her website to fight back the family pressure. Her CV reads: 'Not a womanly woman. Definitely not marriage material'. Looking for: 'A non-family guy, who doesn't like kids and can hold a conversation for at least 30 minutes'. “I know I don't want what is considered a mainstream marriage, which is basically settling for what you get,” she says. The CV went viral, and Pillai got written about in the press, both national and international, while messages from 'suitable' men poured in. “I responded to everyone who got in touch. People found it funny and sarcastic,” she says, glad that her unusual idea at least managed to take the pressure off at home.

Nearly 15,000km away, for Deepica Mutyala, 26, a popular beauty video blogger in New York, it was a childhood game with friends that came as a blow to her self-esteem. Though she would want to dress up as Posh Spice [of the former famous girl band Spice Girls], she would end up as Scary Spice because of her skin colour. “I would want my younger self to know I don't need to change anything about myself to fit in because it is cooler to stand out,” she says. “Kids need to know that the unique aspects of ourselves are what make us who we are. We should encourage people to embrace those rather than moulding them to fit into societal norms. Who decides what normal is?”

She took her idea further by launching 'Be Your Own Princess' videos, where she dresses up as her favourite Disney characters, including Prince Charming. “It is funny hearing, 'You look like Mindy Kaling!' or 'I see so much of Priyanka Chopra in you!' Both comments are flattering, but also racist,” says Mutyala. “No one would tell Britney Spears that she looks like Madonna because they are both blonde Caucasian women in entertainment!” The reason for doing this is to help change the way south Asian women are perceived as well as to make a career out of her passion rather than her father's doctor dreams for her.

Indhuja Pillai

Indhuja Pillai

Pillai and Mutyala, both ordinary young individuals, seem extraordinary for choosing to break stereotypes in their personal spaces. And, there are many more. “We see it every day, in our lives, lives of our coworkers, read of it in the newspapers...,” says writer Annie Zaidi. “More girls are literate and looking to build careers. More careers are opening up to the possibility of having women around. More women are writing, making films and travelling. More men, more parents and colleagues are adjusting to this change quite happily.”

In popular culture, actor Priyanka Chopra has been lauded for her role in the American TV series Quantico, one that is said to have changed how Indians have been long seen—'meek' with 'funny accents'. As an American FBI agent, Chopra is shown to be unapologetic, both about her shortcomings or for having sex with a stranger. It is a role that the 33-year-old actor hopes would broaden the prism for how Indians are perceived. In an industry known for back-biting, an editorial also observed how Chopra receiving effusive encouragement across social media from her women peers for the international foray reflected a positive change in mindsets. Back home, actor Vidya Balan has stood out for experimenting with woman-centric films like The Dirty Picture, Kahaani and Ishqiya that have been game changers at the box office, as has done Kangana Ranaut, who has been celebrated for essaying strong-layered female characters in films such as Queen and Tanu Weds Manu.

When it comes to busting myths, social institutions such as marriage and relationships have been the more obvious ones. Last year, a popular matchmaking app launched a 'Breaking Stereotypes' campaign that went viral on social media. It showed young Indians holding placards with messages such as, 'I'm from Delhi and I'm not a rapist', 'I wear red lipstick and I'm not easy', 'I'm a Jat and I read Karl Marx', 'I'm a man and I love to cook'. “We were wondering what makes people reject a potential profile, and it came down to preconceived notions such as north Indians thinking south Indians are conservative or Bombay men hate Delhi men,” says Shirin Rai Gupta, 23, who led the campaign. “Instead of matching people on age, height and income, we devised personality quizzes to ensure people were open-minded and didn't judge each other on stereotypes. We worked with discriminations in everyday life.”

Keeping in with what the young want, some months ago, marriage portal Shaadi.com came out with a new commercial, 'My Conditions Apply', aimed at the career-driven Indian woman, where relationship, not tradition, is the focus. At the same time, another portal, Bharat Matrimony, came out with a social campaign, 'Let's Break Stereotypes' that posed meaningful questions to young people on marriage, such as partners retaining maiden names and men helping out with household chores. In advertising, Myntra has launched a campaign to let women buy clothes according to their body types; Dabur Vatika, a shampoo brand, celebrates women who have lost hair to cancer and remain beautiful; Titan Raga, featuring actor Katrina Kaif, urges women to marry for the right reasons; while others such as Fastrack even looked at sexuality and coming out of the closet for lesbians.

A smattering of TV serials, too, have been incorporating socially progressive tracks since 2013. Bhaage Re Mann on Zindagi channel looks at the story of a free-spirited 39-year-old woman, and Aadhe Adhoore deals with infidelity and relationship issues. Where earlier serials like Tara, Hasratein, Saans and Shanti left in their depiction of women, a clutch of these new ones claim to take them further. “Indian television is now trying to break stereotypes of how women are projected,” says Priyanka Datta, cluster head, Zindagi and Zee Anmol. “Most serials get stuck in seeing them as somebody’s wife, sister, mother and never as an individual. While this appeals to a mass audience, there is a need to go beyond—depict them as they are: intelligent, evolved, aware of who they are and what they want.”

In recent mainstream films, Angry Young Goddesses (AYG) was hailed as India's first female buddy film, while Tamasha could be seen as trying to evolve the man-woman equation. “I felt a gap between cinema and contemporary society,” says AYG filmmaker Pan Nalin. “Young Indian women aren't just talking about nails and weight loss.... There are strands woven around friendships that help them tide over relationship, career issues that are central to their lives. The characters had to be women you would see at railway stations, at work or in cafes.” But, more needs to change in mainstream cinema. “Most actresses are seen as fair, sexy and who can dance. Of late, there have been several mixed race actresses who can't speak Hindi and wear bikinis,” says Nalin. “Will, say, a half-British actor who can't speak Hindi get a good role here? The disparity points to the hypocritical nature of our industry.”

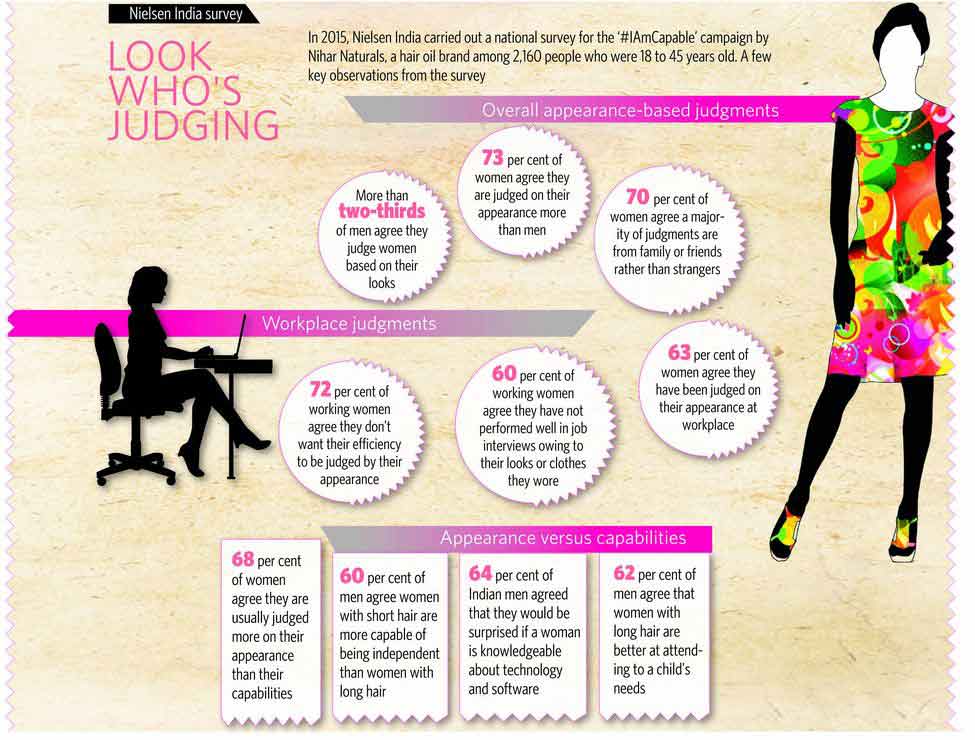

Graphics: N.V. Jose

Graphics: N.V. Jose

It is not always easy to push the envelope. Last year, the 'Kiss of Love' campaign, launched by a group of young people in Kochi as a protest against moral policing, managed to garner support from across the country. But it drew the ire of right-wing fundamentalist groups, leading to several clashes between the protesters and police. Those working on the ground, however, say it is important to keep pushing back. “Everyday notions shape us. How we look at people tells us about ourselves,” says activist Kavita Krishnan. “People from the northeast have long been wrongly termed as 'chinkies', [seen as] those away from mainland India, caught in insurgencies and who eat weird stuff. Over time, people tend to only see through these lens and not the person. Why can't people from Manipur and Nagaland be seen without these stereotypes, in terms of what they want as a group? Or, why should feminists be seen as feminazis?” The manufacturing of prejudices, she says, has happened at systemic levels, and all that must be questioned.

Delhi-based NGO Step recently held an interactive exhibition—'I'm Not A Stereotype'—where groups of students from Delhi, Kashmir and Manipur put together a photography book, capturing everyday discriminations and their thoughts on them. “The idea was to explore dialogue in a democracy and target the urban middle class generally seen as apathetic,” says its founder Shreya Jani, 35. “We want them to engage more critically. For example, most just refer to their domestic help as bhaiya and didi. Why should the person who cleans your toilet not be allowed to use it? In the quest to become something, young people today are losing their right to be lost and confused, where confusion is valuable because it means you are having a dialogue with your surroundings.”

The larger issue of breaking stereotypes is then to explore how building bridges across religious, cultural and geographical divides helps foster peace and understanding in a democracy. Breaking stereotypes is then an equity concept. "We are also looking at redefining masculinity, where it is not about aggression and patriarchy but making men more nurturing, caring beings," says Kamla Bhasin, whose One Billion Rising campaign was recently part of Gender Mela, a college fest in Delhi.

Sonali Khan, country director at Breakthrough, an NGO that works with gender issues, says while there is an effort to claim space and rights, there is a push back from the other side. “Society allows certain concessions within stereotypes,” she says. “So while women can work, they can't loiter in public spaces like men. The 'happy to bleed' campaign recently was a good one in addressing age-old myths around menstrual taboos, but will it change things for women in the real world?” Breakthrough has come out with two recent social media campaigns addressing stereotypes: 'Mission Hazaar' that deals with the issue of skewed sex ratio and 'Share Your Story', where a mother shares her daily tale of dealing with harassment on the street with her son instead of it being only a father to son equation. In the case of some TV commercials and films, says Khan, communication is playing a critical role in creating a different gender dialogue.

Crowning glory: Deepica Mutyala dressed up as Prince Charming for her 'Be Your Own Princess' video.

Crowning glory: Deepica Mutyala dressed up as Prince Charming for her 'Be Your Own Princess' video.

Writer Mrinal Pande disagrees slightly. “As a concession to gender equality, lately one sees men shop online like mad for a baby shower for a female colleague. What is the final message? Buy, buy, buy,” she says. “Three men sitting with bowls of newly re-released noodle brand; does it establish men in a new role? Driven as the ads are with a commercial agenda, can they ever be a vehicle to change gender perceptions?” Others like Anshul Tewari, founder of the youth-centric portal Youth Ki Awaaz (YKA), prefer to be cautious. “Mainstream media is still not talking about stereotypes. While brands such as Havells, Myntra [a recent ad shows a pregnant woman walking away from her job] have created progressive ads, filmmakers such as Karan Johar and actors like Salman Khan are stuck in old moulds. It is heartening that more conversations around intricate issues are happening now. Earlier, no one even thought about a pregnant woman and her issues at the workplace.” YKA is hosting a conversations-based seminar on sociopolitical and art issues for young people, where everyday heroes will talk about how they raised the bar by challenging the status quo.

As humans, we seem to be programmed to a default setting, says Rajani Thindiath, editor, Tinkle Comics. “We tend to pigeon-hole others into comfortable categories for our judgement and convenience. It is a struggle to let people just be.” In all communication, we use the male pronoun, with the result that when we think of a ‘doer’ it is always a male. “How often do you visualise a woman when someone mentions a reporter, a police officer, an engineer? Most of this learning is imbibed from childhood. So if we are to make any difference, then we have to address the child,” she says. On their part, comics are now using both female and male pronouns and gender neutral terms as well—chairperson and human power instead of chairman and manpower, for instance—even if it means stepping beyond the boundaries of defined grammar. While there are iconic male characters like Suppandi, Shikari Shambu and Tantri the Mantri, there is also the Ina Mina Mynah Mo series about four sisters with parents who encourage their individuality, or characters like Aisha from SuperWeirdos, Maya from PsyMage and Mapui aka Wingstar.

All societies grapple with their own stereotyping issues. For instance, Isis Wenger, a 22-year-old American, faced backlash for being 'too pretty' to be a real engineer. She retorted with a campaign 'I look like an engineer' that went viral and got support from Melinda Gates and Chelsea Clinton. What is happening in India has also found resonance in other parts of the world. Berlin-based feminist and online activist Jasna Strick, 26, who was in India for a conference on women's writing last year and is best known for her campaign 'Outcry', says the gruesome gang-rape in Delhi influenced her work, too. “We felt solidarity with the feminists in India and when it came to launching 'Outcry', the outpouring of stories by women led it to becoming a big campaign. It was heartening to see a hashtag influence classical media.”

But, we still have a long way to go. “The visible and voluble young featured in the media and ads come from a small privileged English centric and urban group,” says Pande. “They have not been exposed much to the rural or urban under-classes. They are well meaning, but lack the immediacy that Indian languages and folk idioms alone can give a campaign.” She says in contrast to Anna Hazare's simple message or the poems of S. Kovan in Tamil Nadu, much of the activism in media and ad world comes across as derivative and imitative of trends in the western pop culture. “Calls for flash mobs for events like Slut Walks and gender issue related Dubsmashes and comic standups like ABC lampoons mostly fail to ignite the imagination or present fresh ideas for breaking stereotypes,” she says. “They are becoming the new stereotypes.”

Rizio Yohannan Raj, writer-educationist, suggests the road ahead for stereotypes to be naturally broken is to evolve engaging methodologies to “connect the many splendoured histories and geographies of our country and generate exciting conversations among them”. We need a third wave of feminism to bring some sense into an increasingly chaotic gender scene, adds Pande, where men feel insecure and unsure about masculinity, and girls, too, are often insecure, uneasy and dissatisfied with life within and outside homes, and where marital violence, expensive weddings and dowry practices under another name continue. “What we need are not publicised events but small and intense group discourses in all Indian languages,” she says. “We need to discuss real issues of daily lives of men and women simultaneously.”