On March 5, Raymond Tomlinson died, and the tech world went into mourning. Ray, 74, was a cult figure in the geek community: In 1971, he designed a program that allowed ARPANET users to send messages between connected computers. Just as ARPANET laid the foundation of the internet, Tomlinson’s program became a precursor to email.

“Ray was the man who brought us email in the early days of networked computers,” said a spokesperson for Raytheon, an American defence contracting firm that employed Tomlinson. On March 6, Gmail’s official handle tweeted: “Thank you, Ray Tomlinson, for inventing email and putting the @ sign on the map.”

On March 7, another tweet created ripples across the internet. It was from V.A. Shiva Ayyadurai, a 53-year-old American entrepreneur whose parents had migrated to the US in the seventies. “I am the low-caste, dark-skinned Indian who did invent email—not Raytheon, who profits from war, death and lies,” read the tweet.

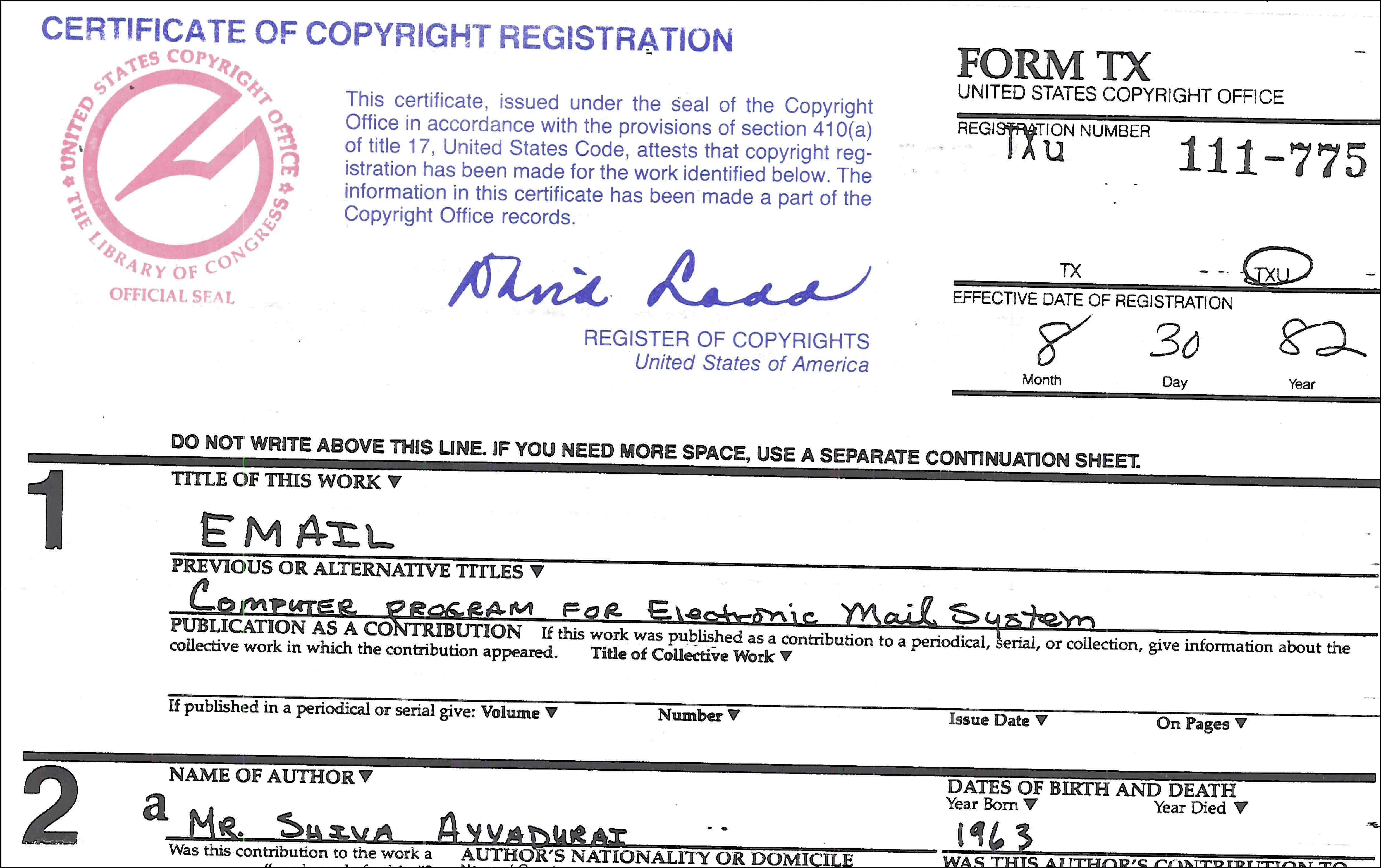

It was followed by an open letter, as incendiary as a Molotov cocktail. Ayyadurai wrote he was not being given recognition for his achievement because of his race and the colour of his skin. “The truth is, I invented email in 1978 when I was employed as a 14-year-old research fellow at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey,” he wrote. “I had been assigned to create a software that duplicated the features of the Interoffice Mail System, which was simply a manila envelope that physically circulated around a workplace…. I named my software EMAIL (a term never used before in the English language), and I received the first US copyright for that software, officially recognising me as ‘the Inventor of Email’, at a time when copyright was the only way to recognise software inventions….”

The letter made waves in the cyberspace. There was an outpouring of support for Ayyadurai on Twitter, mainly from Indians and Indian expatriates across the world. As he began retweeting the supportive tweets, the online chatter about who really invented email gathered momentum. Those who were intrigued, asked Google: “Who invented email?”

The reply was puzzling: at the top of the results page, in a boxed snippet, Google showed the picture of a man and his name in large font—V.A. Shiva Ayyadurai.

Inventor or imposter?

“If I were a white guy, and I had a copyrighted email, and I called it ‘email’, and had all the documentation, as I do, I would be on every stamp in the world,” Ayyadurai tells me over the phone. He is at his office in Cambridge, Massachusetts, thousands of kilometres and dozens of time zones away. But the way he speaks, his voice patient, professorial and passionate, we could as well have been in a classroom together—the teacher trying to explain a complex concept to a struggling student.

Ayyadurai is a Fulbright scholar who holds three degrees and a PhD from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He is the brains behind several firms, including EchoMail Inc., a $200-million company that counts senators and big corporations as its clients. He is, even by the lofty standards set by the Indian diaspora in the US, spectacularly successful—one who can do well without the blemish of controversies.

He has been called an attention-seeker, but he comes across as someone who would not shy away from a fight. Even during his student days at MIT, he was not afraid to mix academics with activism. “When we came to America, I first came to Paterson, New Jersey, one of the poorest neighbourhoods in the US,” he says. “I have had a unique journey. And, because of that journey, I felt compelled to burn the South African flag on the steps of MIT when I was 17 years old, because I did not like MIT having investments in [apartheid-era] South Africa.”

But, for all his pride in his integrity, Ayyadurai’s reputation lies in tatters. He first attracted the attention of geeks in February 2012, when The Washington Post published a story about the Smithsonian, the world’s largest museum, acquiring “tapes, documentation, copyrights and over 50,000 lines of code” from Ayyadurai. The report said he was the inventor of email and that the Smithsonian was honouring him.

The reaction to the story was savage. Thomas Haigh, a well-known computer historian, published a note saying mail features had become common on timesharing computers in the sixties and that the Post had been duped by Ayyadurai. The note was widely circulated in the tech world. Comments against the story began piling up on the Post website, asking the paper to either take down the report or make corrections. Geeks called Ayyadurai a fraud, imposter, liar and loon, and said he had bought up hundreds of vanity domains—such as InventorofEmail.com, EmailInventor.com and DrEmail.com—to optimise online visibility in such a way that his name always showed up as the inventor of email in search results.

“A controversy was fabricated, and it was fabricated because the facts were so overwhelming that I invented email,” says Ayyadurai. “Raytheon had created a false history that Ray Tomlinson was the inventor of email.”

Proud programmer: A young Ayyadurai showing the design of his EMAIL program to his teachers at Livingston High School in New Jersey, where he studied.

Proud programmer: A young Ayyadurai showing the design of his EMAIL program to his teachers at Livingston High School in New Jersey, where he studied.

Why did Raytheon do that? “Because they had created their entire brand as the ‘inventors of email’, which allowed them to win cybersecurity contracts,” he says. “In 2014 alone, they won over $230 million in contracts. Raytheon’s brand is based on Tomlinson being the inventor of email. This [branding] is no different from, for example, Nike saying it is the inventor of the athletic shoe and using Michael Jordan as its mascot. When my materials went into the Smithsonian, I was essentially exposing Raytheon’s false branding.”

Tech historians say otherwise. They say Tomlinson was the first to devise a method, whereby he used the @ sign to enable users to send electronic messages between terminals connected to different servers. Richard R. John of Columbia University puts it bluntly: “If a bus had hit Shiva two years before he won the Westinghouse Prize [as a teenager], the history of email would not have changed a bit.”

Ayyadurai, however, argues that his critics are deliberately blurring the difference between electronic messaging and actual email. “Electronic messaging is not email. It refers to any technology that can send messages electronically,” he says. “Telegram is electronic messaging, because you use electricity to transmit a message.… These people are very clever and big liars. They equate electronic messaging to email and say I am not the inventor of electronic messaging. But I never claimed to be the inventor of electronic messaging. I am the inventor of email, which is not the same thing as sending simple text messages between computers.”

Ayyadurai says his software had all components that are now familiar in email, such as the inbox, outbox, folders and archive. He named it EMAIL (all in upper case, because of the naming conventions of the programming language). To date, it is the only copyrighted computer program for an electronic mail system.

But the nerds, according to him, just won’t give him the credit.

The India connection

The email issue is not Ayyadurai’s first brush with controversy. In 2009, he was recruited by the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) in India to head a company called CSIR Tech, which was meant to help scientists launch businesses. “My job was to be the CEO of the new organisation,” he says. “In over 70 years, CSIR hadn’t really produced anything. It was meant to be a hub for Indian innovation… but it had become, very frankly, a useless organisation nowhere near its original mandate.”

To bring a turnaround in its fortunes, Ayyadurai drew up a business plan, whereby he would help identify marketable innovations, launch businesses and help find customers. The scientists would become stakeholders in the companies.

The plan, according to him, was foolproof. But Samir K. Brahmachari, then CSIR director-general, thought otherwise. “He didn’t want to give me the resources he had promised me,” says Ayyadurai. “In fact, Brahmachari did not want me to do anything. They [the CSIR leadership] thought that I was going to be happy having a nice bungalow in Delhi, that I would be like window dressing.”

The fallout was bitter. Ayyadurai was shown the door and his plan was shelved. Not one to go gently without a fight, he accused CSIR top brass of fostering “a medieval, feudal environment” and a “culture of sycophancy”.

The certificate of copyright for EMAIL.

The certificate of copyright for EMAIL.

The acrimonious exit was not what Ayyadurai had expected. He had jumped at the opportunity to return to India, the homeland of his parents. Ayyadurai’s parents were Nadars, a caste listed as ‘other backward class’. “My mother, Meenakshi, who hailed from Tirunelveli, was a mathematician. My father, Vellayappa Ayyadurai, was an engineer. He was born in Burma and was raised by his grandfather, who went to the country when he was 13, as an indentured servant,” says Ayyadurai. “My parents are very unique people. They came from extremely humble backgrounds, were hardworking and were incredibly fortunate to have been educated when the caste system was predominant.”

The CSIR row ended Ayyadurai’s great Indian dream. He returned to the US and embarked on a fight he was determined not to lose—the fight for recognition as the inventor of email.

Though geeks have largely been successful in discrediting him, he has received support from big names such as Noam Chomsky, professor emeritus of linguistics and philosophy at MIT. According to Chomsky, “Email, upper case, lower case, any case, is the electronic version of the interoffice, inter-organisational mail system, the email we all experience today. And email was invented in 1978 by a 14-year-old working in New Jersey. The facts are indisputable.”

Also pushing Ayyadurai’s cause is the Rutgers School of Biomedical and Health Sciences, which took over the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, for which his EMAIL program was designed. In short, the fight for the fatherhood of email is not over yet.

“It has taken 80 years for people to recognise that J.C. Bose built radio before [Guglielmo] Marconi. The facts are black and white,” says Ayyadurai. “Why is it taking 30 years to recognise V.A. Shiva Ayyadurai as the inventor of email, when the facts are also black and white?”