There is a comical moment over dinner in Siddhartha Mukherjee’s handsome penthouse apartment in Manhattan, not long after he has served up a stunning starter of wasabi-tinged mushroom soup, and just before he has followed it up with a delicious main of slow-cooked salmon, when he refers to the writer Atul Gawande as “one of those overachieving types”.

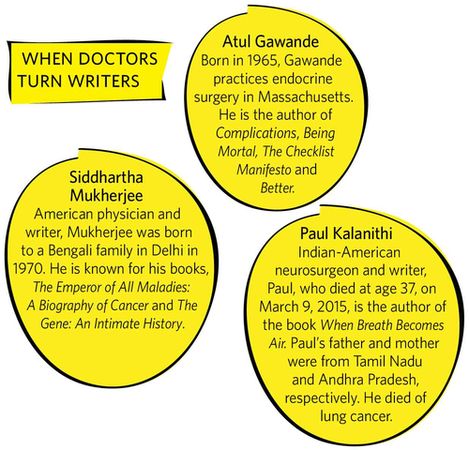

Which is undeniably true. Gawande is an internationally successful surgeon, writer and public health researcher who is not only saving lives via his work on reducing deaths in surgery, but also churns out bestselling books, not least Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End, which must count as some of the finest science writing around. But Mukherjee, who, like Gawande, is a graduate of Stanford University, Harvard Medical School and a one-time Rhodes scholar at Oxford University, is right up there with him.

When the 45-year-old Indian-born physician is not running a laboratory that has identified genes that regulate stem cells, he is working one day a week as an oncologist, helping patients with cancer. When he is not publishing technical articles in Nature, The New England Journal of Medicine and Cell, he is delivering soaring prose on science to The New Yorker. And like Gawande, Mukherjee has written an internationally acclaimed book—The Emperor of All Maladies: a Biography of Cancer, which won a Pulitzer prize and was named one of the 100 most influential non-fiction books by Time magazine.

Indeed, along with the late neurosurgeon Paul Kalanithi, whose bestselling memoir When Breath Becomes Air was published last year, Mukherjee is among a new breed of American physicians, many of whom just happen to be of Indian origin, redefining popular science writing. “Overachieving is the wrong word for Atul,” concedes Mukherjee when challenged on the remark after dinner, speaking slowly in perfectly formed sentences, as he always does, in a gentle accent.

We are sitting in his roof garden at dusk, sirens blaring out on the streets of Chelsea below. “Really the word for him is ‘excellence’. He’s a systems thinker: his brain is very different to mine. When I’m confronted with a problem, I’m usually not saying, ‘How can I rearrange this system to solve the problem?’ I’m saying, ‘What is the question?’”

The question I have, as it happens, travelled across the Atlantic to hear him tackle, is the one that he poses in his dazzling new book, The Gene: An Intimate History—what becomes of being human when we learn to “read” and “write” our own genetic information? As with The Emperor of All Maladies, Mukherjee’s latest book is a history, but whereas the former travelled from Ancient Egypt, where cancer was first identified by the Egyptian physician Imhotep, to modern America,where it kills 6,00,000 people a year, The Gene tracks centuries of research and experimentation into heredity from Aristotle and Pythagoras to Mendel and Darwin.

Like Emperor, it is framed as a kind of biography, but while that first book was “an attempt to enter the mind of [an] immortal illness, to understand its personality, to demystify its behaviour” in the way, said The New York Times, “a passionate young priest might attempt a biography of Satan”, the character at the heart of Gene is more elliptical.

And both books are highly personal.

Emperor began as a response to Mukherjee’s distressing experience of training in cancer medicine, written as a way to avoid “drowning”, as he put it; Gene being inspired by his own family’s harrowing experience of severe mental illness—with one late uncle, Rajesh, suffering from schizophrenia, another late uncle, Jagu, experiencing bipolar disorder, and Moni, a cousin, being confined to “an institution for the mentally ill” in India with a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

When [Mukherjee] met Sarah [his wife], he told her about “the splintered minds of my cousin and two uncles. It was only fair to a future partner that I should come with a letter of warning."

When [Mukherjee] met Sarah [his wife], he told her about “the splintered minds of my cousin and two uncles. It was only fair to a future partner that I should come with a letter of warning."

“Madness, it turns out, has been among the Mukherjees for at least two generations,” he writes at the start of the book, before citing studies exploring the possibility of genetic explanations for severe mental illness. “If Moni’s illness was genetic, then why had his father and sister been spared? What ‘triggers’ had unveiled these predispositions? How much of Jagu’s or Moni’s illnesses arose from ‘nature’ (i.e. genes that were predisposed to mental illness) versus ‘nurture’ (environmental triggers such as upheaval and discord)? Might my father carry the susceptibility?”

As it happens, these are difficult questions that I have also grappled with in print: my father and sister also suffer from schizophrenia, and I wrote The Boy with the Topknot about the experience of only discovering the fact in my mid-twenties. I, though, come from a working-class Punjabi family with no great tradition of education, so I am frankly astonished that someone as middle class, educated and scientific as Mukherjee could have been as oblivious.

“One of my [late] uncles lived with us [in India] and I think the word ‘schizophrenia’ was used in my family when I was growing up,” he recalls, playing with a red thread around his wrist. “But, you know, Indians have a capacity to raise denial to a museum art. And as you know, it’s a culture driven by shame.” So when did he really work things out? “It was years later, in medical school, that I realised that Rajesh’s [his father’s brother, who died prematurely in Kolkata at the age of 22] mental breakdown was the result of a near-textbook case of manic depression—bipolar disease.” He was, around that time, considering becoming a psychiatrist. “I thought about it seriously. But I found it personally difficult, much more difficult than treating cancer. The whole thing really came back to me when I went to visit my cousin Moni in Kolkata in 2012, that’s when the whole thing hit me the most acutely.”

The book describes the visit: Mukherjee’s ageing father accompanying him from Delhi to the asylum in Kolkata as “a guide and companion”; Moni “kept densely medicated awash in a sea of assorted antipsychotics and sedatives”; his father reluctant to accept Moni’s diagnosis. “Over the years, he has waged a lonely counter campaign against the psychiatrists charged with his nephew’s care, hoping to convince them that their diagnosis was a colossal error, or that Moni’s broken psyche would somehow magically mend itself.

“My father has visited the institution twice—once without warning, hoping to see a transformed Moni, living a secretly normal life behind the barred gates. But my father knew—and I knew—that there was more than just avuncular love at stake for him in these visits. At least part of his reluctance to accept Moni’s diagnosis lies in my father’s grim recognition that some kernel of the illness may be buried, like toxic waste, in himself.”

Which perhaps explains why those of us with mental illness in our families are sometimes so slow in facing up to the truth: we don’t want to face up to the possibility that we might be afflicted, too. The book explains that the genetic picture is murky on this front—“even though many variants of schizophrenia have been linked to mutations in single genes, hundreds of genes are involved—some known and some yet unknown”.

But it is a possibility Mukherjee found himself confronting as a teenager when, “during a six-month flirtation with teenage angst”, he ceased speaking to his parents, refused to turn in homework and was “dragged” by his father to see the doctor who had diagnosed one of his uncles. He also admits that when he met Sarah, now his wife, for the fourth or fifth time, he told her about “the splintered minds of my cousin and two uncles. It was only fair to a future partner that I should come with a letter of warning.”

Does he still worry? “Actually, I worry more for my children [two daughters, aged six and ten] than for myself. I think that’s natural.” Has he been depressed as an adult? “I’ve had difficult periods. I remember at a certain time in my life that I went through treatment for depression. For me, I have to say, it’s not the depressive component that worries me; it’s the manic component.” Has he been diagnosed with manic depression? “Far from it. I don’t want to trivialise people who suffer from real manic depression. I went through tough times, then I recovered and it was fine.” It’s probably foolish to attempt to diagnose a world-famous doctor, but I suggest he might suffer from something that I dub “superkid syndrome”: children who, in the words of the psychiatrist E. Fuller Torrey, “try to compensate for their ill family member by being as perfect as possible”.

“No,” comes the response after a pause. “You know, there are two lenses to this: [one being that] children compensate. The more complicated lens—and we know very little about it, so I don’t want to overstress it—is that at least for children with bipolar illness, their siblings seem to have a greater tendency to cluster around creative professions.”

I begin to understand why Mukherjee might be seduced by this theory. He may be a scientist, but artistic endeavour is the thing that shapes and defines his life.

When I ask about the family reaction to the revelations in his book, he says it has been “extremely emotional… it was as if all their grief and fear had been lanced”, but indicates that, for him, the story was the only thing that mattered. “The book went in its own direction… If you reveal things about your family, it’s not always pleasant. If you reveal things about yourself, it’s not always pleasant. And so, approval is not something I always sought: it was not my goal.”

Mukherjee is also an accomplished musician, having been trained as a singer of classical Indian music, taking lessons every day after school throughout his childhood. And he is a talented gardener, with his response to the question, “So you’re obviously into gardening?” epitomising his almost ludicrous intelligence and creativity. “You know what, I would say that, for me, both cooking and gardening are about tending.”

He puts a shawl around his shoulders to protect him from the cool evening breeze. “What’s interesting is that the word ‘tending’ shares something with ‘tenderness’. It also shares something with ‘tension’. I find that very, very important, that distinction between tenderness and tension, that the things you pull are also things that you can break, and therefore need attention.”

Then there is his relationship to Sarah Sze, an American sculptor of English, Scottish and Chinese heritage who as a MacArthur Fellow received a so-called $500,000 Genius Grant for her work in 2003. Their life together is the subject of a breathless article in Vogue magazine in the week of our meeting, in which she is described in the headline as “An Artist Redefining Sculpture”, him as “A Pioneering Scientist and Author” and the pair as “The Most Brilliant Couple in Town”.

Among other things, the article tells us how Mukherjee knew Sze’s work before he knew her; how they met when he invited himself to dinner with her friends after an opening; how they married at City Hall in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 2004; how they discuss each other’s work (she reads his manuscripts, and he sees everything she is up to in the studio); how their friends include everyone from Salman Rushdie to Zadie Smith; and how, while they both travel the globe separately for their work, the whole family visits India every year.

It all sounds too good to believe, laughable even, especially the bit where Sze is quoted remarking, “We knew we were going to spend our lives together and have children, the marriage part was just a detail.” But I can report that the set-up is very real and perhaps even more envy inducing in the flesh. When they are not putting on lavish dinner parties for dazzling guests, they are playing charades with their beautiful multiracial daughters while their fluffy papillon dog pads around amazing artworks from around the world. They are also sweetly attentive of one another: Mukherjee cooking and asking after his wife and Sze bringing him up green tea in return as we conclude our conversation.

For the first time in his career, though, Mukherjee’s dedication to creativity has got him in trouble. The New Yorker recently published an article by him on epigenetics, which echoes some of the content of the new book, and while many readers responded positively, it has been sharply criticised by bloggers. He winces over his tea. “You know, in retrospect, I do think that we should have covered all the long history of gene regulation in that piece. There just wasn’t space. And that’s a trade-off that one makes.”

Is it the first time he has had negative feedback? “If you do public work, you get negative reviews. I read them, I take them seriously, you know. My first reaction to them is defensive, inevitably, but then my general reaction is I come back, about a week or two later, and I read them again, and I try, I really try, to make sense of them.” In the days after our meeting he publishes a point-by-point rebuttal of the criticisms online. “Look, a natural distortion occurs when you choose one story over a hundred stories. You just have to accept that idea and live with it.”

In the spotlight: Mukherjee (centre) with filmmakers Ken Burns (to his left) and Barak Goodman, who made a documentary based on 'The Emperor of All Maladies'.

In the spotlight: Mukherjee (centre) with filmmakers Ken Burns (to his left) and Barak Goodman, who made a documentary based on 'The Emperor of All Maladies'.

I’m not, frankly, qualified to adjudicate, but for what it is worth, epigenetics is a notoriously controversial area of research and Mukherjee has admitted erring by omitting certain areas of science. When I get in touch, even one of his critics, John Greally, who studies epigenetics at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City, admits that Mukherjee’s book is more accurate and thorough than The New Yorker article.

Indeed, there is nothing about Gene that is less than nuanced. Mukherjee pays tribute to the discoveries that have helped identify clear genetic factors behind diseases such as Huntington’s and cystic fibrosis and raises the dazzling implications for future genetic discoveries: a world in which, “when a child is conceived, every parent is given the choice of testing the foetus using comprehensive genome sequencing in utero”; where “a child with a predilection toward a genetic form of obesity, for instance, might be monitored for changes in body mass, treated with an alternative diet, or metabolically ‘reprogrammed’ ”; where “cancers are comprehensively analysed by documenting the mutations responsible for driving malignant growth”.

He admits in the acknowledgements for Gene that when he completed the final draft of Emperor he was spent, experiencing both “physical exhaustion” and “exhaustion of imagination”. But another book came along, and now he is thinking of yet another, this time on “what immortality means”. Could it be a response to Gawande’s Being Mortal?

“When I read that book—which I loved and admired—I thought to myself, ‘Well, what does it mean, being immortal? What would that look like?’ Maybe it would be a smaller book, I don’t know.” A Short Book about Immortality is not a bad title, actually. “Yes, A Short Book about Immortality. A Brief History of Time! I don’t seem to be able to do short books very well, but maybe I’ll try.” Somehow, I suspect, it will turn out to be a triumph.