One of the greatest heavyweights or the greatest of all time: by common consent, this was the only area of debate so far as the boxing career of Muhammad Ali was concerned. Otherwise, he was universally acknowledged as the most charismatic and politically significant individual ever to have entered the ring. No one else, not even Joe Louis, who ruled the division between 1937 and 1949, winning the respect and affection of Americans.

Beginning in 1960, when he won an Olympic gold medal in Rome, Ali was rarely out of the news for the next 20 years, during which he dominated heavyweight boxing’s golden age, notably with the “Rumble in the Jungle” in 1974 and the “Thrilla in Manila” the following year. For some years he was the most famous man in the world, a judgment he did not dispute. As he put it with his trademark cod candour: “It’s hard to be humble when you’re as great as I am.”

He was born Cassius Clay, the descendant of slaves, but he outfought not only his opponents, but the boxing establishment and the US military, both of which tried hard to ensure that he joined the army and took his fight to Vietnam, which he was not prepared to do. He had no quarrel with Vietnam, he said. “No Viet Cong ever called me n**r.” Instead, having been stripped of the title he had won, aged 22, by demolishing the fearsome Sonny Liston, he deployed his matchless wit and flamboyant sense of theatre to bring his race and his Muslim religion centre-stage in an era when prejudice was the default position of white America.

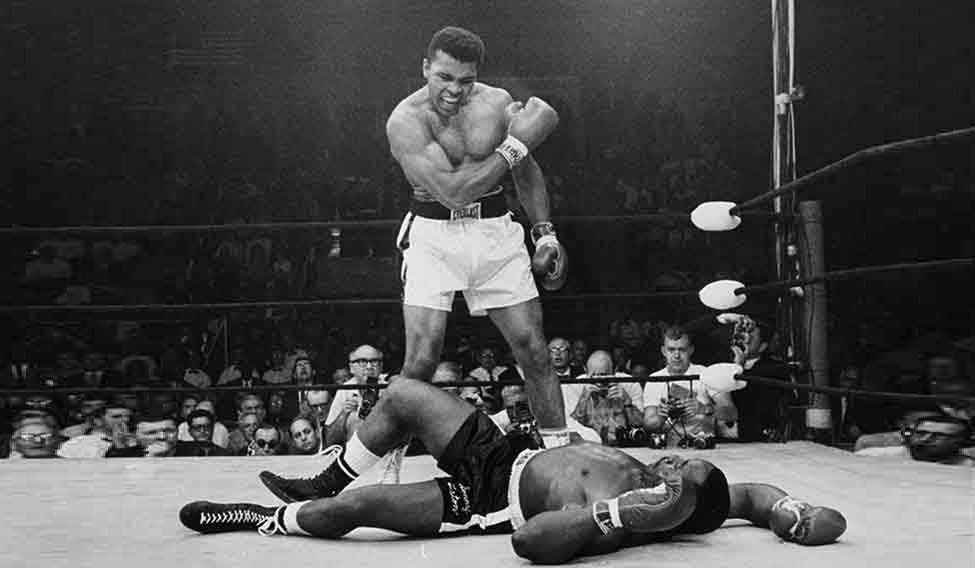

His rematch with Liston was the most anticipated fight in boxing history. There was no way “the big ugly bear” was ever going to beat him, Ali told a press corps, many of them hoping to see exactly that. “If Liston even dreamt he could beat me,” he taunted the former champion, “he’d wake up and apologise.”

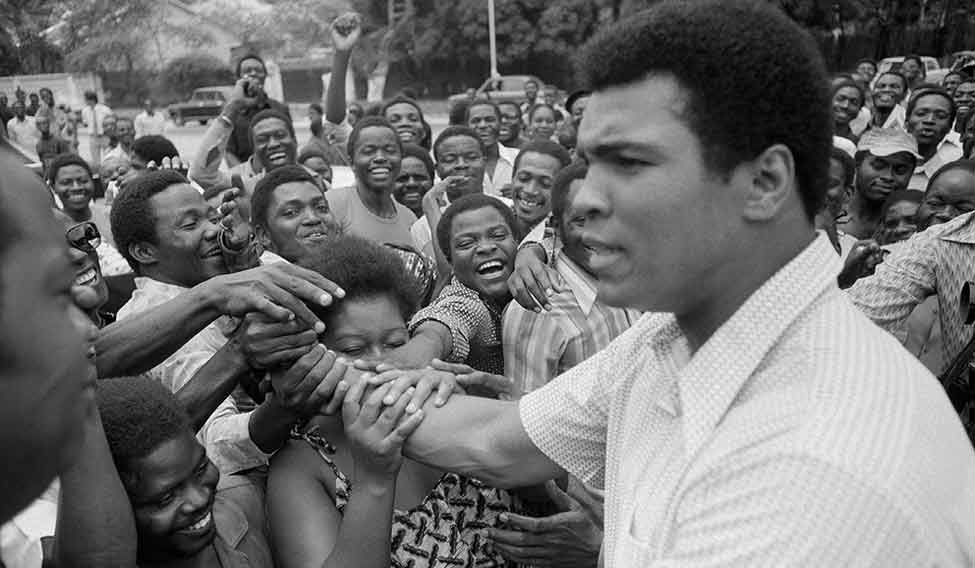

Mr Charmer: Ali being greeted in Kinshasa, Congo. Ali went there to fight fellow American boxer George Foreman | AP

Mr Charmer: Ali being greeted in Kinshasa, Congo. Ali went there to fight fellow American boxer George Foreman | AP

His fight against conscription went on for four years, ending in the Supreme Court in 1971, where, by a vote of 8-0 (the sole black justice having abstained), his status as a conscientious objector was finally endorsed and his rights restored. Ali then launched into a sequence of fights that took him to the pinnacle of boxing. By the time he retired, in 1981, suffering from the onset of Parkinson’s disease, he had become a powerful symbol of dignity in adversity.

Inevitably, the life and the legend were two different things. Ali’s image as a husband and father was tarnished by marital breakups and frequent reports of womanising, and there were ugly disputes towards the end of his life over who would inherit his fortune worth, at its peak, between $50 million and $80 million—less than half of that accumulated by Britain’s Lennox Lewis decades later. Whatever the truth about his human failings, it is the mark he left in the development of black consciousness that is likely to prove indelible.

In a 1974 interview, Ali denied that he supported confrontation between the races. At the same time, he couldn’t forget the centuries of “lynching and killing and raping” of his people, when they were the “lowest of the low and the least respected”. Was he supposed to look at the minority of white people who were trying to do right and not see the millions who were out to kill him? “I’m not that big a fool.” Boxing, he said, was not something he particularly valued. It was a stepping stone to introduce him to the audience. “My main fight is for freedom and equality.”

Muhammad Ali, baptised Cassius Marcellus Clay, was born in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1942, the third of four brothers. He also had a sister. His father, Cassius Sr, was a billboard painter; his mother, Sallie, with origins in Madagascar, worked in domestic service. Young Cassius had a secure upbringing, but in spite of his sharp natural intelligence, took little interest in school.

He became interested in boxing, it was said, after a bigger boy stole his bicycle when he was 12, which made him want to “whup” the thief. As an amateur, coached by a former police officer, he was awarded six Kentucky Golden Gloves and went on to win gold in the light-heavyweight division at the Rome Olympics. He recalled in his autobiography that he threw his medal into the Ohio River after he was refused service in a whites-only diner. “A few minutes earlier,” he wrote, “I had fought a man almost to death because he had wanted to take it from me... now I had thrown it in the river. And I felt no pain and regret. Only relief, and a new strength.” In fact he lost it, and was given a replacement after he lit the flame to open the Atlanta Games in 1996. Clay, as he still was, made his professional debut in 1960. His opponent, Tunney Hunsaker, a West Virginia police chief, said after the fight: “[He] was fast as lightning... I tried every trick I knew to throw him of balance, but he was just too good.”

Over the next three years, as the “Louisville Lip”, the nom de guerre given to him by often prejudiced sportswriters, he won all of his 19 fights, most by a knockout. Yet while dedicated to his trade, he never lost his awareness of a wider world. He had grown to manhood at the time of the civil rights marches that would convulse his country, and—while he could have had no idea of it at the time—became an inspiration to no less a figure than Martin Luther King. It was his decision, early in his career, to join the Nation of Islam (known as the Black Muslims), led by the controversial Elijah Muhammad, that brought him into conflict with boxing’s administrators and power-brokers, all of them white. He was warned that his licence could be revoked. State boards refused to allow him to use his Islamic name and continued to bill him as Cassius Clay. It was only when, against all the odds, he “whupped” Liston, who was tall and strong as an ox, that the critics began to realise the truth that underpinned Ali’s outrageous claims.

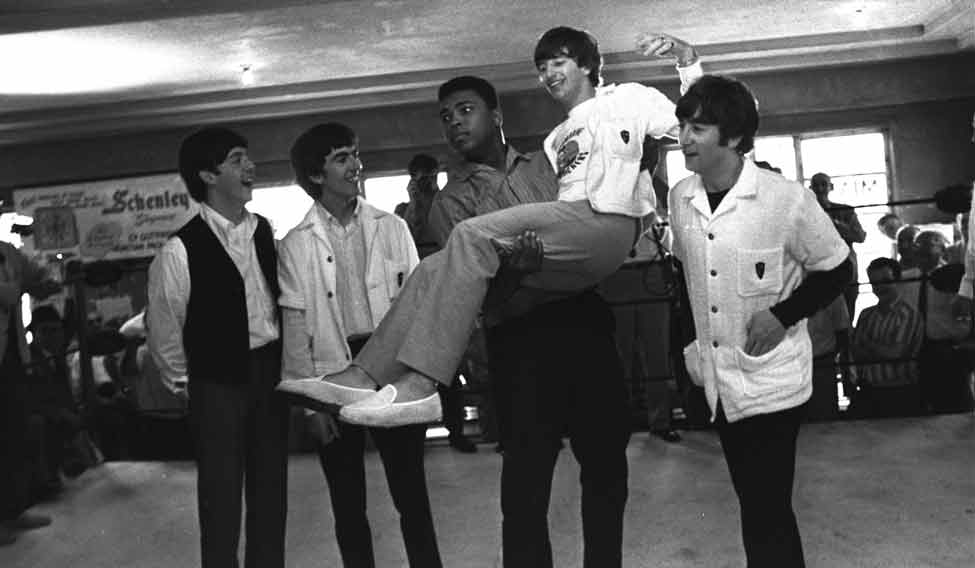

Fun time: Ali lifts Ringo Starr, musician and drummer for the Beatles | AP

Fun time: Ali lifts Ringo Starr, musician and drummer for the Beatles | AP

Never once did he make it easy for them. Sportswriters hoping to gain his respect were required to accept him not just as the greatest boxer of the age, but as a complete and integrated package that included a world-view and an uncompromising embrace of the demand for civil rights. His devotion to his adopted religion was fierce and unbreakable. In addition, he exploited his fame and position as no other fighter before him. Handsome—entirely unmarked by his trade — and supremely gifted, he was bumptious, conceited and openly contemptuous of the men in suits who got rich from boxing without ever getting hurt.

It was also on the eve of the first Liston fight that Ali revealed his talent for verse:

“Now Clay swings with a right, what a beautiful swing,

And raises the Bear straight out of the ring;

Liston is rising and the ref wears a frown,

For he can’t start counting ’til Liston comes down.

Now Liston disappears from view, the crowd is getting frantic,

But our radar stations have picked him up somewhere over the Atlantic.”

Who would have thought when they came to the fight

That they’d witness the launching of a human satellite?

Yes the crowd did not dream when they laid down their money

That they would see a total eclipse of the Sonny.

This was irresistible. Afterwards, when he declared, unequivocally, “I am the greatest!”, no one demurred.

So long as he was winning, and winning in style, there was nothing they could do. He disposed of a string of contenders, including the former champion Floyd Patterson, Liston a second time and, most notably, Ernie Terrell, whom he tormented over 15 brutal rounds. Terrell made the mistake of calling him by his “slave name”. For this, he had to be “tortured”. A clean knock- out was too good for him. “What’s my name, Uncle Tom?” Ali shouted over and over again, as he went about his work. “What’s my name?”

Just prior to the Terrell demolition Ali had rammed this particular point home. “Cassius Clay,” he told journalists, “is a slave name. I didn’t choose it and I don’t want it. I am Muhammad Ali, a free name. It means Beloved of God, and I insist people use it when people speak to me and of me.” Terrell should have listened. Ali’s next opponent, Zora Folley, went out of his way to accord the champion his Islamic nomenclature. As a result, he was seen off quickly. He would show the same respect to Britain’s Henry Cooper, beating him in six rounds in front of 40,000 people at Highbury in north London in 1966.

An unforeseen comeuppance was on its way. When Ali refused the draft in 1967 on the grounds of his faith, those he had derided were delighted by his discomfiture. The army made it difficult for him to find places to box and then his licence was removed along with his title. He made speeches in defence of the Nation of Islam, proclaiming that Black is Best and that African-Americans (as they would soon be termed) were still being repressed and held back by their former masters.

“My enemy is the white people, not the Viet Cong,” he said. “You’re my opposer when I want freedom. You’re my opposer when I want justice. You’re my opposer when I want equality... you want me to go somewhere and fight when you won’t even stand up for my religious beliefs at home.” The Supreme Court’s ruling was a triumphant vindication of his stand. There was no time, however, in which to rejoice. As his long-time trainer Angelo Dundee said, Ali had lost four of the best years of his boxing life and was determined to get right back in the money.

The years of plenty followed. At his imperious peak, Ali brought skills to his art that were unique. He danced around his opponents, displaying footwork that Fred Astaire would have appreciated, so that they were left flailing in his wake. When they attempted a killer punch, his head would, in anticipation, dart backwards so that the incoming fist struck only empty air. If they chose to grapple, he would stand against the ropes, absorbing everything they could throw at him, mocking their efforts, before stepping out of the way and raining punches of his own.

Before each of his fights, he goaded those about to face him. He was convinced that if he could wound their pride in advance, they would try too hard, too early. Ridicule was as much his weapon as his fists and his prodigious reach. Even when fellow-fighters stood their ground, his “rope-a-dope” defence, his middle-of-the-ring “Ali-shue”, and, above all, his claim to “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee”, ensured that all but the best were dispatched before Ali broke sweat.

One scare tactic that especially enraged opponents was his habit of announcing in advance the round in which the contest would end—usually in a knockout. “Liston must go in eight,” was an early boast. “It ain’t no jive, Henry Cooper will go in five!” was another. He wasn’t always right about the round or the manner of the victory, but the psychological edge his forecasts provided were unquestionably unsettling for those on the receiving end. “I’m not the greatest; I’m the double greatest,” was how Ali put it. “Not only do I knock ’em out, I pick the round.”

None of this was to say that he was unbeatable. In 1963, in a celebrated encounter at Wembley stadium, Cooper set the home crowd alight when he unleashed ’Enry’s ’Ammer, his legendary left hook, which struck home from an unexpected upwards angle. Ali was literally saved by the bell, then further assisted when his “cutsman”, backed by the ever-cynical Dundee, alleged that one of his gloves had split and had to be replaced — a ploy that bought an additional two minutes of recovery time. Revealingly, although the Wembley crowd was overwhelmingly behind Cooper, and disapproving of Ali’s delaying tactic, they quickly forgave the charismatic American, whose wit, pride, good humour and unstoppable optimism made him a firm favourite in the UK throughout his career.

Ali’s first and most famous defeat, in Madison Square Garden on March 8, 1971, came at the hands, or fists, of his fellow all-time great, “Smokin” Joe Frazier, who, enraged by Ali’s exhaustive pre-match taunts, “stole” his title in the “Fight of the Century” by the simple expedient of punching hard and punching often and ignoring what he regarded as the flummery of his opponent’s technique.

Even then Ali had the last laugh. Having outpointed Frazier in a lame return match, a non-title fight that refused to live up to its billing, Ali restored full bragging rights in the Philippines four years later. Having stretched himself in training, he made good on his boast that the contest would be “a killa and a thrilla and a chilla, when I get that gorilla in Manila”. Yet victory did not come without cost. The fight, he told journalists in a rare moment of self-awareness, “was the closest thing to dying that I know”. Frazier, he later conceded, was “the greatest fighter of all times... next to me”.

In between his two bouts with Frazier, Ali had overcome the new champion, George Foreman, an intimidating figure who would himself win the title three times. The “Rumble in the Jungle”, in Kinshasa, co-promoted by the Zairean dictator Mobutu Sese Seko, was a grimly gladiatorial encounter, but it was Ali whose technique and stamina eventually won the day. By stopping Foreman in the eighth round he secured the title for the second time, displaying not only his mastery of the ring but his ability to take the sort of punishment that had left Foreman’s previous victims sprawling on the canvas.

While progressive, if combative, on the issue of race, Ali was no feminist. Rather, he was a man of his time. He could never marry a white woman, he said. “I don’t want to lose my beautiful identity. I don’t want no half-white, half-brown children. No woman on the whole Earth can please me and cook for me and socialise and talk to me like an American black woman.”

His women may all (or mostly) have been black. In no other respect, however, did Ali impose limits on the range of his sexual activity. “I used to chase women all the time,” he told one of his biographers. “And I won’t say it was right. But look at the temptations I had. I was young, handsome, heavyweight champion of the world. Women were always offering themselves to me.”

Ever the Muslim, Ali confessed that his behaviour had “offended God”. Ever the man, he couldn’t help himself. “A man who views the world the same at 50 as he did at 20,” he said, “has wasted 30 years of his life.”

Ali’s use of language, even when obviously prepared, was frequently sublime: “I’ve wrestled with alligators,” he told an unsuspecting world in 1974. “I’ve tussled with a whale. I done handcuffed lightning and thrown thunder in jail. You know I’m bad. Just last week, I murdered a rock, injured a stone, hospitalised a brick. I’m so mean, I make medicine sick.” His audience roared.

Yet he could also be cruel. “Frazier is too ugly to be champ,” he said before their second bout. “Frazier is too dumb to be champ. The only people rooting for Joe Frazier are white people in suits, Alabama sheriffs and members of the Ku Klux Klan. I’m fighting for the little man in the ghetto.”

This did not go down well with Frazier, a proud man whom Ali would go on to admire and whose funeral he attended in tears. “What the f* does he know about the ghetto?” Frazier asked.

Eastward journey: Ali with former prime minister Indira Gandhi | PTI

Eastward journey: Ali with former prime minister Indira Gandhi | PTI

It was in the nature of things that Ali’s late career was marked by decline and a sense of departed glory. In 1978, Leon Spinks, an indifferent heavyweight, beat him on an off-night in Las Vegas, leaving Ali’s famously “pretty” face puffy and bruised and, more importantly, his ego in tatters. Spinks won the crown, but it was the boxing world’s sense of shock that made the headlines. “I let him rob my house while I was out to lunch,” was Ali’s own verdict. The sport was in mourning and, however unfairly, Spinks was portrayed as a journeyman who had got above himself. Even when Ali recovered, got himself in shape and won the return bout (securing the title for the third and last time), the sense of anti-climax was pervasive, prompting “The Greatest” to announce that he was retiring to spend more time with his religion and family.

It did not last. Allegedly because he needed the money, but just as likely because his self-esteem required constant administrations of acclaim, he decided he still had some fight left in him. It was his next contest, against Larry Holmes, that revealed he could no longer defend himself against top-class opponents. Holmes, the new champion, had not sought the fight. He did not want to be the one who destroyed a legend. Yet Ali, aged 38 and weakened by a thyroid condition, was determined. Inevitably, he lost. It was a depressing spectacle. The actor Sylvester Stallone, who starred in the Rocky movies, said it was like watching an autopsy on a man who was still alive.

Even then, Ali refused to give up. He fought one last fight, against Trevor Berbick, losing in ten rounds when he was judged unable to continue. After that, his physical deterioration was rapid and unstoppable. As the Parkinson’s from which he had suffered ever since the Holmes fight gradually robbed him of the power of speech, taking from him the articulacy that he prized, all that remained to him was immortality, which he wore like an ill- fitting suit.

Late in his career, he reflected on it. Characteristically, he did not underplay his achievement. “When will they ever have another fighter who writes poems, predicts rounds, beats everybody, makes people laugh, makes people cry, and is as tall and extra pretty as me? In the history of the world and from the beginning of time, there’s never been another fighter like me. Eat your words! Eat your words! I am ‘the Greatest’.”

Ali married four times and had seven daughters and two sons. His first wife was Sonji Roi, a cocktail waitress, who refused to adapt to her husband’s new religion. She was his toughest fight, he said, and they divorced after less than two years. Belinda Boyd was next in line. She converted happily to Islam, taking the name Khalilah, and even followed her husband into Sufism in later life. The couple had four children, Maryum—who grew up to be a rapper—twins Jamillah and Rasheda, and Muhammad Ali Jr.

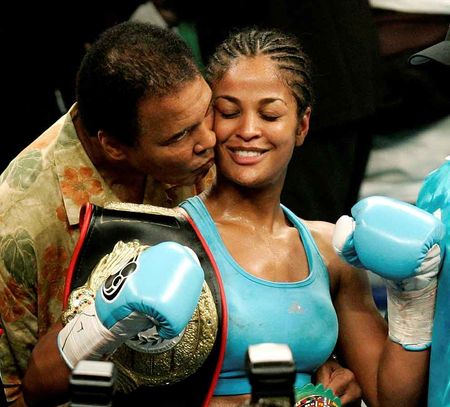

An affair with Veronica Porsche, a stunning teenage model whom he took to President Marcos’s house while in Manila, was the immediate cause of Ali’s second divorce. Porsche and Ali stayed married for nine years, producing two daughters: Laila, a professional boxer, and Hana.

Ali’s fourth and final marriage was to Yolanda “Lonnie” Williams, a childhood friend, from Louisville, who also converted to Islam. They adopted a baby son, Asaad Amin. As Ali aged and his Parkinson’s advanced, there were unsubstantiated stories that he was being neglected and that his remaining fortune would not pass to his children.

We'll miss you: Ali kisses his daughter, Laila, 38, who was an American professional boxer

We'll miss you: Ali kisses his daughter, Laila, 38, who was an American professional boxer

Muhammad Jr (b 1972), who is unemployed in Chicago, claimed that he was prevented by his stepmother from getting through to his father. Whatever the truth of these allegations, Ali became something of a recluse as he entered his seventies, though he still made occasional public appearances. Against her father’s advice, Laila (b 1977) enjoyed a successful career as a female boxer, retiring undefeated and starring with the wrestler Hulk Hogan in American Gladiators; Rasheda (b 1970), is a media spokeswoman, fundraiser and president of RAW Dreams, Las Vegas; her twin sister Jamillah worked in the office of the former Illinois secretary of state before marrying an ex-boxer-turned lawyer; Maryum (b 1968) is a social worker, active in gang prevention in Los Angeles; Miya (b 1972), whose mother had an affair with Ali in New York, is a former model; Hana is a teacher and poet; Khaliah (b 1974), another whose mother had an affair with Ali, has written about her weight problems, while Ali’s adopted son Asaad (b 1991) has had an intermittent career playing professional baseball.

Before becoming incapacitated by his illness, Ali devoted a lot of his time to various charitable projects and was received by a number of world leaders, most notably Nelson Mandela. He undertook goodwill missions to Afghanistan and North Korea, took medical supplies to Cuba and travelled to Iraq to secure the release of 15 US hostages before the first Gulf war. In 2005, in recognition of his lifetime achievement, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by George W Bush.

In his last years, the Ali shuffle caught up with him. The one- time Adonis was reduced to a shambling wreck, struggling for breath, able to speak only haltingly, his thoughts coming from a long way off. Yet even in his darkest moments, the dignity and the determination shone through. As a man as much as a fighter he retired undefeated.

His death arrived without fuss or protest. Incapacitated by his illness, Ali slipped in and out of consciousness and died in hospital in Phoenix, Arizona, his preferred home in recent years.

Ali always knew the end would come. All boxing people realised that evening came and night fell, he said. “We all lose sometimes. We all grow old. We all die... when I’m gone, boxing will be nuthin’ again.”

The Times/The Interview People

1960: Wins Olympic light-heavyweight gold medal in Rome at age 18

1964: Wins first heavyweight title at age 22

1971: Loses to Joe Frazier, heavyweight champion

1974: Ali beats Frazier

1975: Beats Frazier again. Ali says the fight is the closest he had come to death

1981: Loses his final match to Trevor Berbick, a Jamaican Canadian boxer

Visits Delhi in the mid-seventies on Rajiv Gandhi ’s request. Fights Indian heavyweight champion Kaur Singh in an exhibition match.

Visits Chennai in 1980. Takes part in an exhibition match against heavyweight champion Jimmy Ellis at Nehru Stadium.

Visits Kerala in 1989 to know more about Kalaripayattu, which he was introduced to by A. Moosa Haji, veteran practitioner of the martial art form.

Visits Kolkata in 1990 on an invitation from a football club and floats magic tricks.