Investigations by the CBI and the Enforcement Directorate into allegations of money laundering against industrialist Vijay Mallya and former Maharashtra deputy chief minister Chhagan Bhujbal have brought a number of “suitcase companies” under the scanner. According to the ED, these bogus companies, which only exist on paper, were used to carry out a web of transactions that helped obfuscate the money trail.

THE WEEK accessed documents that revealed that Mallya used 22 bogus companies to siphon off part of the Rs 900 crore he borrowed from IDBI Bank on behalf of Kingfisher Airlines Ltd, of which he was chairman. According to an ED official, Mallya broke laws by failing to use the money for the purpose for which it was borrowed. “He is suspected to have been primarily instrumental in the diversion and laundering of funds,” said the official.

Bhujbal, too, is alleged to have used several suitcase companies to carry out a maze of transactions to launder as much as Rs 870 crore. According to the ED, these companies were set up by his nephew Sameer Bhujbal with the help of chartered accountants. Documents with THE WEEK list six private limited companies—Shub Chintak, Sudhalak Traders, Nirniddhi Consultants, Sepia Ventures, Unisys Softwares and Holding Industries and Scan Infrastructure—as suitcase companies that were used to launder crores.

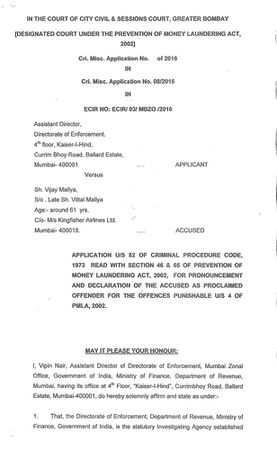

The ED application filed in court requesting that he be declared a “proclaimed offender” under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002.

The ED application filed in court requesting that he be declared a “proclaimed offender” under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002.

Interestingly, these companies are just a few of the several hundred suitcase companies managed by Jagdish Prasad Purohit, a 60-year-old lawyer based in Mumbai. ED officials said Purohit routed the money through his Kolkata-based suitcase companies and that his share of the sum laundered was Rs 46.5 crore. He, along with Bhujbal, was arrested last year, but is currently out on bail.

“Purohit was Bhujbal’s single-most influential accomplice in money laundering,” an ED official involved in the investigation told THE WEEK. “He was involved in all three sequential elements [in money laundering] and had help from shadowy operators.”

The ‘placement’, which ED officials call the first “sequential element” in the laundering process, happens when an illegally obtained sum is deposited or ‘placed’ in a bank. Next, the money is ‘layered’ through random transactions. This is where suitcase companies come into play. It is through them that a complex series of interconnected transactions are carried out. The money is routed through several accounts, companies and, often, countries. It may also change its ‘form’, if the operators choose to buy assets like real estate or yachts. ‘Integration’ is the final stage, whereby the money or asset is made to appear legitimate.

ALL IT TAKES to create a bogus company is a sheaf of documents that can fit into a suitcase and a finance professional who is willing to take the risk of setting up a company to launder money. As is stipulated by law, all companies are required to register with the registrar of companies under the ministry of corporate affairs. But chartered accountants can help set up a company in a way that it is helmed by directors who are not the actual owners of the company. The company need not even have a genuine address or office infrastructure.

A group of such suitcase companies may act as intermediaries between two genuine companies to create a complex web of transactions. For instance, company A and G could be real entities with an established track record. But, instead of A paying a sum to G directly, the money is routed through companies B, C, D, E and F, which could all be dummy entities. These dummy companies can then be used to perform multiple transactions between themselves, in a way that money moves back and forth in the form of equity purchase at unreasonably high premiums, debt issuance, capital funding and so on. By the time the money reaches company G, it would be a fraction of the amount originally transferred by company A, and the mishmash of transactions between suitcase companies would have made auditing difficult.

“One company is never enough,” said Manoj Jain, a Mumbai-based chartered accountant. “You need to have several to rotate your money and create a maze of transactions. And you rotate the money to decrease your tax liabilities.”

In the dock: Bhujbal allegedly laundered Rs 870 crore with the help of suitcase companies | Janak Bhat

In the dock: Bhujbal allegedly laundered Rs 870 crore with the help of suitcase companies | Janak Bhat

Suitcase companies are set up for the benefit of people who have amassed wealth disproportionate to their known income. Experts say such companies “pass off as finance, investment or technology companies” whose area of operations is often difficult to map. They accept unaccounted money and give it an air of legitimacy by bringing it back to their books of account by disguising it as loan or share capital.

In business parlance, such processes are called ‘accommodation entries’. According to the ED, Purohit’s Kolkata-based “employees” offered “one-stop solutions” to those who wanted to legitimise their unaccounted assets. “Purohit also offered banking and accounting services, and legal and income tax-related advice,” said an ED official.

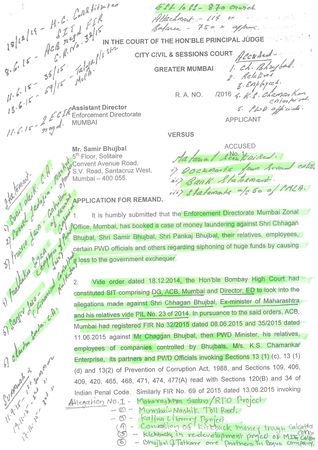

The remand application filed by the ED, which lists the shady transactions carried out by companies controlled by him.

The remand application filed by the ED, which lists the shady transactions carried out by companies controlled by him.

Documents with THE WEEK show that Purohit’s Kumaon Engineering Private Ltd paid the Bhujbals Rs 40 crore. Bank account statements of various companies controlled by the Bhujbals have revealed that nine companies paid them sums ranging from Rs 5 crore to Rs 40 crore. One document says that a chartered accountant called Chandra Shekhar Sarda set up two suitcase companies, “and arranged payments of Rs 10.24 crore and Rs 15.78 crore in the bank account of Parvesh Contructions Pvt Ltd [a company owned by the Bhujbals] in the guise of share purchase at high premium”.

“Often, these dubious entities floated shares, took money from the people and then just disappeared,” said Paranjoy Guha Thakurta, editor of Economic and Political Weekly and an expert on corporate affairs. “For the past several decades, high net-worth individuals, companies and promoters of companies have been using these illegal entities to either avoid paying taxes or launder money.”

SINCE THE LATE 1980s, Kolkata has been the hub of finance professionals who float suitcase companies for a fee. “Those days [late eighties], the volume of business in Kolkata was low,” said Jain. “Regular audit work, too, was scarce. This prompted unscrupulous chartered accountants to create and operate dummy companies, by way of providing fake accommodation entries against commission.”

A trader in the city who is familiar with such operators said chartered accountants who set up suitcase companies get as much as 10 per cent of the amount they help ‘accommodate’—which is “ten times the money [in terms of commission] they would otherwise have made from regular, clean audit work”.

No wonder that Kolkata’s decline as an industrial hub has not affected the boom in the number of chartered accountants practising there. “Take a walk down Bentinck Street, the area around Paradise Cinema, and you can see CA firms that are in the business of providing accommodation entries,” said the trader.

THE ED IS proceeding against Mallya and Bhujbal under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002. But, according to ED director Karnal Singh, not a single conviction has happened in cases related to the PMLA.

According to Union revenue secretary Hasmukh Adhia, the ED investigated 372 such cases last year. But charge-sheets were filed in just 79. “There is always a time lag between the filing of charge-sheet, prosecution and actual conviction by the court. The ED is trying to bridge that gap,” Adhia told THE WEEK.

S. Gurumurthy, chartered accountant and commentator on economic affairs, said there should be a consolidated approach on the part of the government agencies to rein in suitcase companies. “Activities of all listed companies should be monitored by Securities and Exchange Board of India, whereas the unlisted ones, which mostly do not make use of public funds, should come under a separate regulatory watchdog,” he said. “There is an urgent need to not permit one-person companies, since the very mechanism to launder funds is used by all and sundry.”