On a pleasant evening, Prakriti was having an intense conversation with her 22-year-old daughter Roma. “I was telling her that it is high time she took some psychiatric help as she was slipping into depression,” recounts Prakriti, who lives in Pune. But in the middle of the conversation, Roma suddenly got up from the chair, went to her room and locked herself up.

A few minutes later Prakriti heard a sound from Roma’s room. Thinking that her upset daughter might have banged some furniture, Prakriti told her to calm down. “I let her be, thinking that she will, perhaps, sleep on it and wake up just fine,” says Prakriti. But even after hours when Roma didn’t open the door, at about 11pm, Prakriti broke it open to find her daughter hanging from the ceiling fan.

“I still don’t know why she took such an extreme step,” says Prakriti. “And, it is this ambiguity that made coming to terms with the loss so difficult. Perhaps, she put a lot of pressure on herself when she couldn’t crack the IIM entrance thrice, despite being a good student.”

Roma’s story is not an exception. It is an indicator of a deeper issue confronting the Indian youth today. Blame it on the youngsters’ inability to strike a balance between tradition and modernity or a mismatch between aspiration and reality, suicide is no longer a rare occurrence but an epidemic that has this generation in its grip. Compounding the problem is the social stigma attached to mental illnesses.

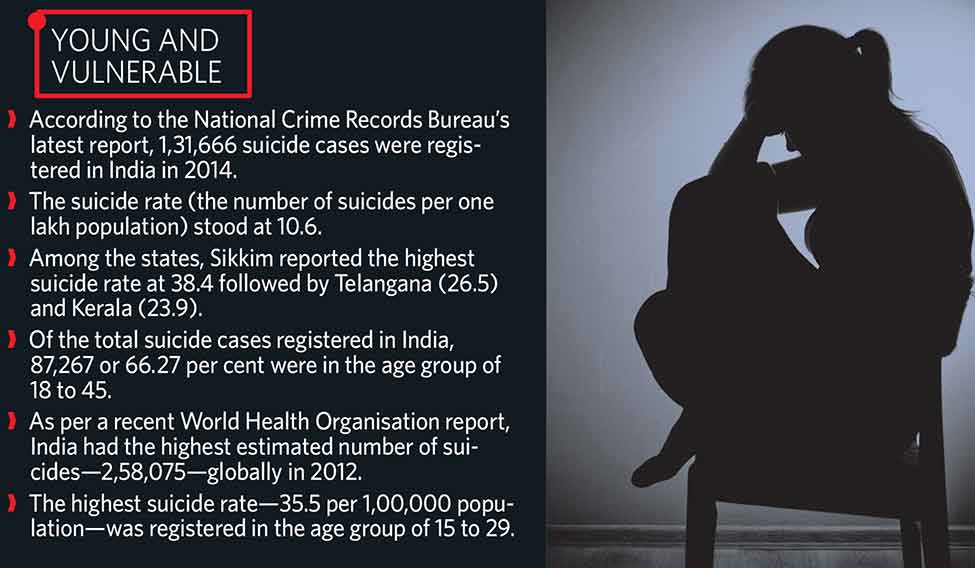

According to the National Crime Records Bureau’s latest report titled ‘Suicides in India’, 1,31,666 suicide cases were registered in India in 2014. The suicide rate (the number of suicides per one lakh population) was 10.6. Among the states, Sikkim reported the highest suicide rate at 38.4 followed by Telangana at 26.5 and Kerala at 23.9. Of the total suicide cases registered in India, a shocking 87,267 or 66.27 per cent were in the age group of 18 to 45 years.

As per a recent World Health Organisation report, India registered the highest estimated number of suicides—2,58,075—globally in 2012. And, the highest suicide rate—35.5 per 1,00,000 population—was registered among youngsters in the age group of 15 to 29 years.

What is worrying is that it is the same age group that has access to the best technology, information, lifestyle, opportunities, and has witnessed maximum socio-economic growth in comparison with the previous generations. Besides, this generation is seen as taking the country forward both socially and economically and allowing it to reap its demographic dividend. So what is it that makes them vulnerable?

This generation has high aspirations and believes in instant gratification, says Johnson Thomas, founder of Aasra, a Pune-based non-government organisation that runs a crisis intervention centre and a suicide prevention helpline. The lingering inequality, poverty and unemployment, too, play a part.

Jobs were a big problem in the last decade. According to the latest economic survey, India created 59.9 million jobs between 1999-2000 and 2004-05. However, between 2004-05 and 2009-10, just 1.1 million new jobs were created. And, between 2009-10 and 2011-12, the numbers went up to 13.9 million. The findings, initially flagged by India’s National Sample Survey Office, gave rise to a debate known as jobless growth.

“When youngsters don’t get what they want, many find it difficult to handle failure and the stark realities of life, and take the easy way out—suicide,” says Thomas. “I call it the aspiration-reality gap.”

Some dub it as an escapist and impulsive behaviour, too. Those attempting suicide are well aware that it is not a remedy for any of their problems, writes Malayalam poet and activist Sugathakumari in the prologue to the book Kerala on Suicide Point. The book, by Dr Siby Mathews, looks at the socio-economic aspect of the high suicide rate in ‘God’s Own Country’. “It is an effort to escape from crisis and difficulties like loneliness and bereavement of loved ones. Dejected and defeated, he knives himself, hangs himself, poisons himself or sets himself afire,” she writes.

Over-protective urban parenting has also boosted the trend, says Thomas. While most parents teach their children the importance of winning, they fail to train them to accept failure with grace. “Not conditioned to experience failure, when faced with it, many don’t know how to respond and slip into depression,” says Thomas.

Hyderabad-based Sujata of OneLife, a non-profit organisation that runs a crisis intervention centre and suicide helpline, however, holds societal changes and growing dependence on technology equally responsible for the growing suicide cases.

Because of rapid urbanisation and development, the Indian society is witnessing changes like increasing emphasis on individual preferences, growing number of double income families, disintegration of the joint family system and greater reliance on technology, she says. “Hectic work schedules and long commuting hours in metro cities restrain parents from spending enough time with children,” says Sujata. “This is where technology creeps in. While people seem connected 24x7 through the internet, hardly any meaningful conversation takes place.”

Diminishing warmth in relationships and social bonds is making this generation distressed. “Even though the older generation had to face struggles in almost every sphere of life, they found happiness, comfort and solace by having a heart-to-heart conversation with family and friends,” says Bobby Zachariah, chief executive officer of Connecting, a Pune-based non-government organisation. “City life has robbed us all of this.” In the absence of these stress-busters and emotional cushions, people gravitate towards material possessions to fill the emotional void. “But it is temporary, and is followed by loneliness and distress in the long run,” he says.

Torn between traditions and modernity, the youth today may find it difficult to connect with the elders. Perhaps that is why when 19-year-old Dhanajay’s parents continued putting pressure on him to get into the best college and scolded him for being indecisive, he attempted suicide by consuming poison. “Elders think life is easy for today’s youth,” says Heena, Dhanajay's elder sister. “But what they don’t realise is while the quality of life has improved, it has become more complex and competition has become tougher, too.”

Heena spoke to Dhanajay to know why he took the extreme step. “He told me that he wasn’t distressed,” she says. “But when he realised that my parents were simply not ready to understand his problems and point of view, he took the step to simply grab their attention and threaten them to a certain extent.”

While the common perception is that women are more prone to depression than men, studies reveal that more men commit suicide. Of 87,267 suicide cases reported last year, 58,002 were men.

The WHO report reveals the same thing. Of 2,58,075 suicide cases registered in 2012 in India, 1,58,098 were men. So, why are men more prone to suicide? Women are more likely to seek help “because they are more comfortable and open about sharing their feelings”, says Zachariah, whose helpline receives at least 100 calls a day. “Likewise, suicide attempts made by men are more fatal than women.”

The clichéd forms of masculinity like showing self-restraint and being macho are killing men, says Thomas. “We operate in a society where men are taught to suppress their feelings,” he says. “Showing emotions or talking about one’s problems is considered to be a sign of weakness. This kind of male identity is cemented at a young age.”

It makes reaching out for help harder for men, as ‘rules of masculinity’ stop them from opening up and seeking help. “To top it all, our society doesn’t look at mental illness as a disease. So, it is accompanied by a sense of shame of not deserving help, which makes matters worse,” says Seeba Bhojani, a coordinator at Connecting.

Changing societal attitude towards people battling psychological distress by creating awareness about mental illnesses, preventive measures and cure is the only way to curb the menace, writes Mathews, who is chief information commissioner at Kerala State Information Commission, in Kerala on Suicide Point. “It is possible to avert a vast majority of suicides, if only a benevolent hand is offered willingly to help them at the right time from slipping into the dark abyss of untimely death,” he writes.

“Otherwise the demographic dividend will turn into a nightmare,” says Thomas. The government plans to train more than 500 million people by 2022 under its national skill mission. A change in the attitude of the youngsters would help India reap demographic dividend as 50 per cent of the country’s 1.2 billion population is below age 25.

(Some names have been changed.)