On June 17, Abhinav Bindra left his sprawling farmhouse in Zirakpur, nearly 15 kilometres from Chandigarh, after what he termed as his “last ever training result at his home range”. The numbers were highly impressive: Bindra had scored 634.6 points (out of the maximum achievable aggregate of 709), with 57 inner tens (shots at the innermost ring of the shooting target). His mother, Babli, had the printout of the result framed.

Bindra, who won gold in the 10m air rifle event at the 2008 Beijing Olympics, left his home as an Olympic medal hopeful, and will return as a retired athlete. The Rio Olympics, which begins in August, will be his last. And Bindra, in his last lap of preparations, is sparing no effort to make it memorable.

He has 51 days and four stops (Baku, Hanover, Serbia and Dortmund) before his event in Rio. His schedule is packed—travel, practise, compete, fine-tune the rifle, and keep his body and mind in the right state. Come August 8, and he will be taking aim to do what no air rifle shooter has ever done before—become an Olympic champion for the second time.

Before he left, THE WEEK got an exclusive peek into his high-intensity training regime at his home range in Zirakpur. Every day, he would be in his shooting range before 9am, getting ready to take aim. The range is located behind the house and faces a kitchen garden lined with pots of flowers and vegetables. The Rio 2016 logo is painted on the white door.

As you enter, your eyes first take in all the photo-frames that adorn the sidewalls and the wall at the back, and then fall on three sets of shooting suits—jackets and trousers, blue and off-white in colour, draped on three chairs. There is a plush, two-seat leather sofa, table, and wooden mirror on wheels, roughly 6x5ft, that is positioned alongside the wall on the right for the shooter to check his posture and position from any one of the three shooting lanes in the range.

The walls of the range are painted green. Each of the three lanes, numbered 27, 28 and 29, has its own rifle stand and electronic target scoring system. A printer on the far left gives Bindra’s scoresheets after every session. Next to the mirror on the right is a table on which rifle parts, tools, pliers, sighters, bolt knobs, stationery and glue are laid out neatly.

Pictures from the historic Beijing Olympics gold medal win on August 11, 2008, and messages from president Pratibha Patil and prime minister Manmohan Singh cabled to the Indian ambassador to China on that day are displayed, as are monograms of all milestone international events Bindra took part in from 1999 to 2006. On the right wall is a big frame of the paper targets he shot at the famous Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs ahead of the 2004 Athens Olympics. Other framed photos show him winning gold at the 2006 World Championship in Zagreb and receiving the Rajiv Gandhi Khel Ratna award in 2001. The photographs are so many that you lose count.

On the wall on the far side, atop the target on the central lane, is the Rio 2016 logo. Bindra said he got the range recreated to resemble the Olympic Shooting Centre in Rio. He had visited the range in April for the test event organised by the International Shooting Sport Federation. “I shot a lot on the range,” he said. “I trained the most among all there…. The Rio range is nice.”

He zipped up his shooting suit, put on his visors and gloves, and took position. For the next hour and a half, there was the silence of Bindra taking stance—his body still, trigger pressed and his back in that awkward position that puts intense pressure on the spinal cord. And the silence was punctuated by the noise of shots being fired. Sixty shots were fired, each one registering on the scoring system. At the end of the session, he took the printout of the score.

Gauging from Bindra’s reaction, it was not a bad day of practice. Not that there have not been bad days. He has trained hard throughout his two-decade-long career, and his back and body have borne the brunt of it. He now divides his time between training at his home and with his coaches, Gaby Buhlmann and Heinz Reinkemeier, at their Dortmund range.

Bindra having lunch with his family at home | Arvind Jain

Bindra having lunch with his family at home | Arvind Jain

“If I have a bad day, I go back to the range four times a day and train,” he said. “Otherwise, I can’t sleep. A couple of weeks ago, I finished training at 9pm; my last session started at 7.30pm. In some ways, when things are not going well, which happens, then I just can’t let go. I have come to terms with that; that is the way I am.”

With the practice over, Bindra took a ten-minute break. “My focus is more on the body,” he said. “In some aspects, it is easier [to train] here…. The facilities and access to experts, sports medicine and doctors are much more here.”

The memory of the 2012 London Olympics, which came after his history-making performance in Beijing, still haunts him—he had returned empty-handed. By the time of the 2014 Asian Games in Incheon, Bindra had announced that he would soon be looking at shooting as a hobby.

His determination to succeed, perhaps, saw him through the tough times. In May last year, he qualified for Rio by winning a quota in the Munich World Cup. Getting a year to prepare for the Olympics has helped. “Not the training part, [but] the mindset,” he said. “There is a lot of stress to qualify because, in shooting, the opportunities to qualify are quite limited. Competition is very high. You don’t want to leave it till the very end.”

He adopts a different approach to prepare for each Olympics. He became an Olympian in Sydney in 2000, as an 18-year-old; Rio 2016 is his fifth Olympics. This time, the training has been different, and harder. “The situation demanded that I work harder,” he said. “My body needed a lot of work since last year. I would say I have a good foundation, and I am in good shape and generally shooting well.”

Each Olympics has been a journey of self discovery for Bindra, 34. Each time, he has sought and found a reason to not merely compete, but also win. He won gold in 2008, because he had lost in 2004 and was ‘needy’ for a medal. He believes he missed out in London 2012, because he wanted to win but was not needy enough. This time, the gnawing need has resurfaced.

“This [preparation for] Olympics has been needy and painful; except, the pain threshold is better, so I don’t mind the pain,” he said. “I have tried to simplify a few things, and I try not to be extremely complicated about a few things. There are a few complicated things in the way I manage my body. There is a complete science behind it. From the shooting point of view, when the body is in a good state, shooting is more easier. It is simpler to execute good shots.”

Details matter a lot to Bindra, so much so that Digpal Singh Ranawat, his trainer, physiologist, strength conditioning coach and travel companion, calls him a half scientist. “It is easier to train for dynamic sports; there is no limit to the gains you can make there,” said Ranawat, as he worked on Bindra. “Shooting is a very intense sport. It is an extreme sport. In the gym, we do very precise work.”

Bindra’s aim is to ensure that his body and mind are in the best possible shape as he lands in Rio. He believes he experimented less ahead of London 2012. To overcome his fear of heights, he had climbed a 60ft pole in Germany before Beijing 2008 and skydived before London 2012. “There is no magic formula that I can follow and win,” said Bindra. “There are lots of factors which will come into play, but I am not aware of right now. The goal is to be awake to those challenges and fight hard to overcome them.”

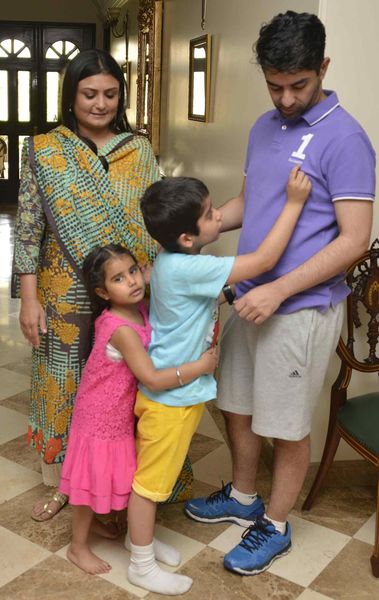

He appeared relaxed after his morning session. We were in the house, and his sister Divya and her children had come from Gurgaon.

Family first: Bindra with his sister Divya and her children | Arvind Jain

Family first: Bindra with his sister Divya and her children | Arvind Jain

The living room is a treasure trove by itself—all the medals he has won so far are neatly framed and hung on the wall. The biggest one, the Olympic gold, stands apart in a wooden cabinet alongside the gold rifle gifted to him by his rifle maker, Walther.

Determined to the point of being obsessive and thoughtful to the point of being analytical, Bindra is up to experimenting again—he is pushing the limits of fitness and learning the science behind the body and mind. “There are certain reasons for that,” he said. “I am an analytical person. Shooting itself is a very monotonous and repetitive activity. So, to make things more interesting, I keep my brain stimulated, and end up doing other things in an attempt to improve.”

Post Beijing 2008, he took a year and half to figure out what to do next. In fact, he even consulted a palmist. After London 2012, he spent months undergoing sessions with Delhi-based hypnotist and healer Radhika Kawlra Singh to figure out what went wrong.

Bindra’s personal gym can easily be the envy of the most advanced gymnasiums in the country. When they are travelling, Bindra and his trainer carry a machine called GMS, an electric muscle stimulator which is not yet available for other Indian athletes. Bindra does a 20-minute session twice a week on it. “One session of GMS is equal to two to three hours of weight training,” said Ranawat.

There is the “slosh pipe”, a pipe filled with water that is used to build body balance and control. Then there is the electrode suit, which records fitness-related data and targets specific muscles that require stimulation. Little wonder that the shooting fraternity acknowledges Bindra as India’s only professional shooter.

Bindra is not just preparing harder this time, but has also become more open to distractions. His niece and nephew ventured into the range and watched him train. Agastya, his nephew, wants to be a shooter like his uncle.

At the lunch table, the Bindra family—his father, Apjit, Babli and Divya—passionately talks about India’s preparations for Rio, the medal hopefuls and the problems sportspersons face. His parents are keen to travel to Rio and see their son lead the Indian contingent as its flag-bearer.

Last time, Bindra had declined to be the flag-bearer. “When I went to London, I was more closed. I declined to carry the flag, as I felt it won’t be good for me. When London got over, I thought maybe I should have gone to the opening ceremony,” said Bindra. “This time, I was planning to go to the opening ceremony in Rio anyway. I am an old horse now. A little bit of motivation can help me.”

He agreed to become a goodwill ambassador for Rio on request of the Indian Olympic Association, which was criticised for selecting actor Salman Khan first. After his appointment, Bindra sent motivational letters to every Rio-bound Indian athlete. He reached Baku days ahead of the ISSF World Cup, and went to cheer boxers who were struggling to qualify for Olympics at the last Olympic qualifier.

“It is a positive distraction. The ISSF work (Bindra is chairman of the athletes committee) is something I enjoy doing,” said Bindra. “Regarding the goodwill ambassador thing, I have not been assigned a role; I assigned a role to myself—sending letters to every athlete. I cannot do much more to be frank.”

Both sports and future cannot be scripted. But one thing Bindra is certain about is his retirement date—August 9. “This is my last games for sure. August 8 is the competition. I have had this clarity since months, a year, or maybe more…. I am very much at peace with it,” he said. “It has taken me a while to get to this point. If you look back, I wanted to quit after Beijing. It has taken me eight years to come to this point, where I can actually let go.”