Rueil-Malmaison in the Paris suburbs is where Joséphine met Napoléon, and nurtured her beloved rose garden. Not far from their château lies Rue des Géraniums, prettily named but with its dull grey concrete apartments housing many struggling migrant families.

It is a dozen kilometres west of Paris. As time goes by, N’Golo Kanté, one of nine children born to immigrants from Mali, might become the most famous son, and among the richest people to come out of Rueil-Malmaison.

He no longer lives there. And Kanté is definitely no delicate flower.

Yet, in a game where his 1.69m, 68kg frame makes him the lightweight on the field, he is on the threshold of making history. Last season, he was the midfield dynamo driving Leicester City to astonish the world by winning the English Premier League. This season, he does a similar job for a Chelsea side that is racing towards the title.

The last regular first team player to win back-to-back championships for different clubs in England was Eric Cantona. But Leeds United was in the old First Division when Cantona led it in 1991-92, and he then won the first Premier League with Manchester United the next season.

Cantona and Kanté are French. They crossed the English Channel to earn fame and fortune in the league of mercenaries. The EPL, like the Indian Premier League, is a magnet for diversity. In its 25 years, England’s top soccer league has attracted players from 106 lands. And, since every man votes in the player of the year poll, it is hardly surprising that the last home-grown winner was Wayne Rooney, back in 2010.

Cantona won with two of the all-time big spenders. Kanté wows his peers from a different perspective. He energised the Leicester upstarts; now he is among Chelsea’s acclaimed stars. Only the blue that both teams wear is the same.

In the presumption of wealth, power and class, Chelsea is expected to challenge for titles. Leicester had reached above its station to be EPL champion at 5,000 to 1. The bookmakers will not be caught out again, at least not where N’Golo Kanté is concerned. They make him such a short-odds favourite to win footballer of the year in England that a punter would have to lay out 12 pounds to win just one back from the bookie.

Players of all sides talk admiringly of Kanté. When Canal+ television in France cornered Kanté and suggested he was sure to receive the honour, he demurred: “It would be something beautiful, but quite a few players in the Premier League deserve this award—in my team alone, Eden Hazard, Diego Costa and David Luiz, for example.”

He probably meant it. Having risen from an amateur in the ninth grade of French football for Boulogne reserve team six years ago to a place in the national side during the past 12 months, he regards his role as a workhorse, an artisan rather than artiste.

Kanté turned 26 on March 29, and strives to replicate his national team coach Didier Deschamps, who captained France to win the 1998 World Cup. His current Chelsea coach, Antonio Conte, captained Juventus to be Italian champion five times, and was runner up with Italy at a World Cup and a Euro finals.

Captains of industry, both. Deschamps was famously disparaged by Cantona. ‘King Eric’ fumed when he was dropped by France, and scorned Deschamps as a “water carrier”, meaning a player of perspiration not inspiration. Conte, similarly, was adored as a workman in Italy’s cause. And, now that Conte and Deschamps select Kanté for club and country, they see themselves in the young Frenchman.

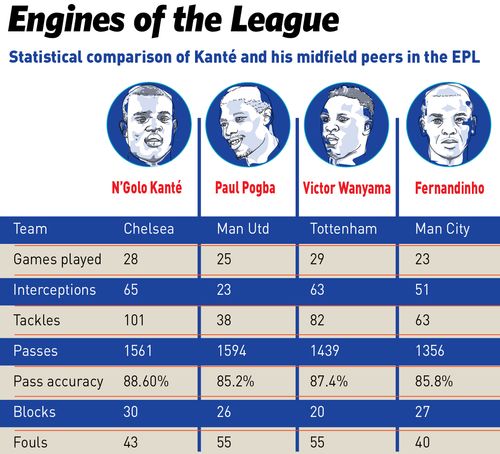

Statistics show that, week after week, Kanté covers more ground, wins more tackles, makes more interceptions, and gives more accurate passes than most midfielders. Up to the end of March, Kanté made 269 tackles—more than any other player in France, England, Germany, Italy or Spain over the past two seasons.

Only two midfield providers in the top five European leagues compare for consistency. One is Real Madrid’s Toni Kroos, the other is Paul Pogba, who cost Manchester United almost £100 million to buy. At 1.91m, Pogba dwarfs Kanté when they stride out side by side for France. But he doesn’t dominate the little fellow when Chelsea plays, and beats, United.

Sure, Eden Hazard, with his quick-silver acceleration, his balance and his goals, can lift sport close to the art of dance. But ‘water-carrying’ also plays a valuable role—a selfless one in gathering the ball and then distributing it. Hazard speaks in awe of Kanté: “I think sometimes when I’m on the pitch I see him twice. One on the left, one on the right. I think he plays with a twin.”

But where does his talent come from, and how was it hidden until Kanté was 23?

For answers, you must go to the Paris suburbs from where other second generation immigrants, including Thierry Henry, emerged playing street football. They often blossom rather late in life, compared to the teenagers who are fast tracked through club academies in Europe or plucked from Africa or South America while still in embryo.

To date, Kanté seldom speaks for himself or about himself. He arrives at training, works as hard as he does in games, and quietly slips away to his apartment, where he lives alone in leafy upmarket Surrey.

It was ever thus in his life. At age eight, playing among boys three years his senior, he joined Suresnes. “He was half the size of the others,” recalls Pierre Ville, the head coach at Suresnes. “But when he started to play, he outclassed them all. He is so extraordinary, he has a balancing effect.”

Kanté spent 11 years at that first club. Coaches admit that they seldom knew what he was feeling inside. His father died when he was 11, but the family still lives in that apartment.

Andy King, a midfield colleague at Leicester, observed that the key to Kanté is a combination of anticipation and instant control of the ball. “If I, or anyone else, tackles someone, the ball ricochets away,” said King. “But if he tackles, the ball sticks to his foot. Or, if you smash the ball at me, it rebounds. Smash it to him, and it seems to hit him and land at his foot, and then he runs away with it.”

King isn’t the first to notice it. People in the Rueil-Malmaison and Suresnes area knew well enough that the teams played differently and were better balanced, when Kanté was on the pitch. And, maybe 50 more spectators would gravitate to the parks where the games took place.

Where there is even a small crowd, there usually are professional scouts eyeing up the talent. The biggest club in France, Paris Saint-Germain, plays at Parc des Princes, just across the river Seine where Kanté was born. The people at Suresnes will tell you that it was not just PSG, but Lorient, Rennes, Sochaux and other first division clubs that looked at Kanté without seeing his worth.

At 19, almost beyond the age of senior recruitment, Kanté did move across the river. He joined Boulogne’s reserves and then moved again to FC Caen where he helped them to secure promotion, to Ligue 1.

From there, Leicester’s top scout Steve Walsh spotted what France overlooked: That size mattered less than Kanté’s energy, desire, and willingness to serve the teams he plays for.

Caen paid nothing for him, and made £5.6 million profit by shipping him across the Channel. Leicester drafted a £32.5 million buy-out clause into his contract, allowing Chelsea to pay the sum that, it seems, has transferred the Premier League title with Kanté from Leicester to London.

His mode of transport at Boulogne was a child’s scooter. He completed his studies in accountancy there. At Caen, two hours north of Paris by train, he bought his first car, a second-hand Renault. At Chelsea, his shiny white Mini Cooper nestles in the car park alongside the Mercs, Porsches, Range Rovers and Bentleys of his colleagues.

Former Chelsea defender Frenchman Frank Leboeuf sums up Kanté this way: “He’s an incredible soldier, a warrior, an essential player to Chelsea and to France. He has neither the personality nor the calibre of a leader. [But] he will get you the ball 8,00,000 times every game, and give it to the offensive players in the team.”

Essential, yet humble.The embodiment of a team player who is about to be recognised by his peers as the best among them over the season.