In the scenic mountains north of Manali, at an elevation of 1,189m, lies the small village of Burua. If the weather is clear, one can spot paragliders in the sky, against a lush green backdrop. And, the snow-capped mountains are a skier’s delight.

“That is ‘commando’ Roshan’s house,” says a villager, pointing to the most beautiful bungalow in the village. Roshan Thakur lives there with his wife, Ram Dai, and his children, Himanshu and Aanchal, who regularly participate in international skiing championships.

Thakur, who got the nickname ‘commando’ after a short stint with the Indo Tibetan Border Police, is the secretary of the National Winter Games Federation. “We get around two metres of snow and everybody in the village skis mainly for entertainment, not competition,” says Thakur, who started with wooden skis. “After we realised that plastic had better sliding properties, we ripped plastic off buckets and attached it to our wooden skis,” says Thakur.

In 1978, he won the bronze in the National Games “on borrowed skis”, which landed him a job with the ITBP. “That was a message to the youth of Burua, and they got serious about skiing,” says Thakur. Earlier, most Indian participants in international skiing events were from Kashmir or the Army. Today, Thakur’s and his sister’s children are regulars in international skiing competitions. “Burua kids are now participating in international championships because this is our home game and it is our advantage. If somebody from Delhi comes here, he won’t be able to even walk in the snow,” says Thakur.

Adventure tourism started in Manali only after 1989, when violence erupted in Kashmir and tourism there came to a standstill. “In Kashmir, skiing attracted several tourists because of Gulmarg’s excellent skiing slopes and better facilities such as air connectivity. People from Bombay would just fly there for training, which wasn’t possible here. Our skiing slopes are equally good, but other facilities need to be improved,” says Thakur.

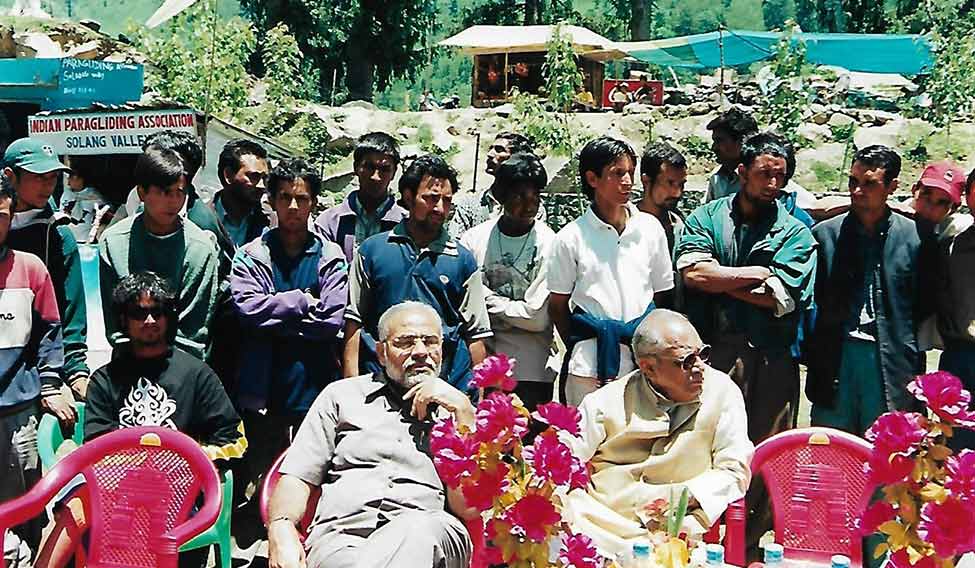

After spending a couple of years in ITBP, Thakur turned his attention towards skiing and paragliding. He started paragliding after convincing a foreigner who had come to Burua to sell his equipment for Rs 13,000. Thakur, who has a C certificate from the NCC’s air wing, says he has completed 150 flights, the durations ranging from one minute to 10 minutes. He became so famous that Narendra Modi had sought his guidance to try paragliding. Modi used to accompany former prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee on his trips to Manali. On those occasions, he would travel up to Burua for paragliding. “Modiji bade tagde adventurous hain [Modiji is highly adventurous],” says Thakur. “He would say, ‘Chalo bhai, gliding karte hain [Let us go gliding],’ and since 1997—when he came here for the first time—he has returned a few times,” says Thakur. “Today, 90 per cent of paragliding pilots are from my village because they followed me. They make Rs 5,000 to Rs 10,000 a day,” he says.

Hira Lal with his mother | Sanjay Ahlawat

Hira Lal with his mother | Sanjay Ahlawat

Thakur’s son Himanshu is an Olympian. The 23-year-old started skiing at the age of nine. After participating in the Sochi Winter Olympics in 2014, he has now qualified for three events in the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, South Korea. His younger sister, Aanchal, has participated in nearly 60 International Skiing Federation (FIS) races and also in the first Youth Winter Olympics held in Innsbruck, Austria, in 2012. Both are undergraduate students at DAV College, Chandigarh. “Our exams always clash with the national championships, but our parents leave the decision to us,” says Aanchal. Their cousins Varsha and Hira Lal are also international skiers. Hira Lal, 37, has participated in the Olympics, Asian Games and world championships, starting from the 2006 Winter Olympics in Torino, Italy. Although he still participates in international events, Hira Lal says he is “almost retired”, and has turned his attention to coaching. Together, the four cousins represented India in the World Skiing Championship in Schladming, Austria, in 2013; in Colorado, USA, in 2015 and in St. Moritz, Switzerland, this year. Another cousin, Saurabh Thakur, a Class XII student from Manali, participated in the 2016 Youth Winter Olympic Games in Lillehammer, Norway.

“Skiing is not a priority for our leaders, nor do they have any knowledge about the sport,” says Thakur. “We need ropeways and snow-grooming machines. We have natural mountains, but we may need to cut a slope slightly or move a tree, which are minor things. If we get those done, we can develop facilities for future generations and have international events right here. If winter tourism develops, locals, too, will prosper.”

“Earlier, we held so many competitions in Gulaba [near Manali], now we can’t do so because the National Green Tribunal stopped it. So, for practice, we have to go to Europe,” says Hira Lal. In Burua, too, training is not so easy, according to Aanchal. “For training, we need hard snow, but it is warmer here, and the snow melts and gets soft. So, we can only do four to five rounds. After that, it turns into a water–ski event,” she says.

To train for the upcoming Olympics, they are planning to go to Europe from June to December. “Training abroad isn’t cheap,” says Hira Lal. “The fight begins even before we board our flights. Each skier travels with around 80kg of equipment, and most airlines have a problem with that.” Then, there are fitness issues. Aanchal says foreign athletes are very tall and follow different diets. “Our diets are that of a normal sportsman.”

A file picture of Narendra Modi in Manali.

A file picture of Narendra Modi in Manali.

According to Hira Lal, the Indian skiers follow a strict training regimen while abroad. “We wake up at 6am. The ski lift starts at 8am and we have to go and place the markers in minus 30 degrees Celsius, wearing thin clothes. Practice is from 8am to 8pm and we break only for lunch.”

He says foreigners differ in their preparation compared with Indians. “They start training their kids when they are as young as two years. By the time those kids are 17 or 18, they start winning gold medals. They practice for nine months a year and have two or three coaches each, who charge nearly ¤500-600 a day,” says Hira Lal. “India can definitely participate in international championships, but most of the time we do it with our own money. To win medals, we need to train like foreigners and with them. For that, we need money, almost Rs 1 crore for each season. Only then will we get medals.”

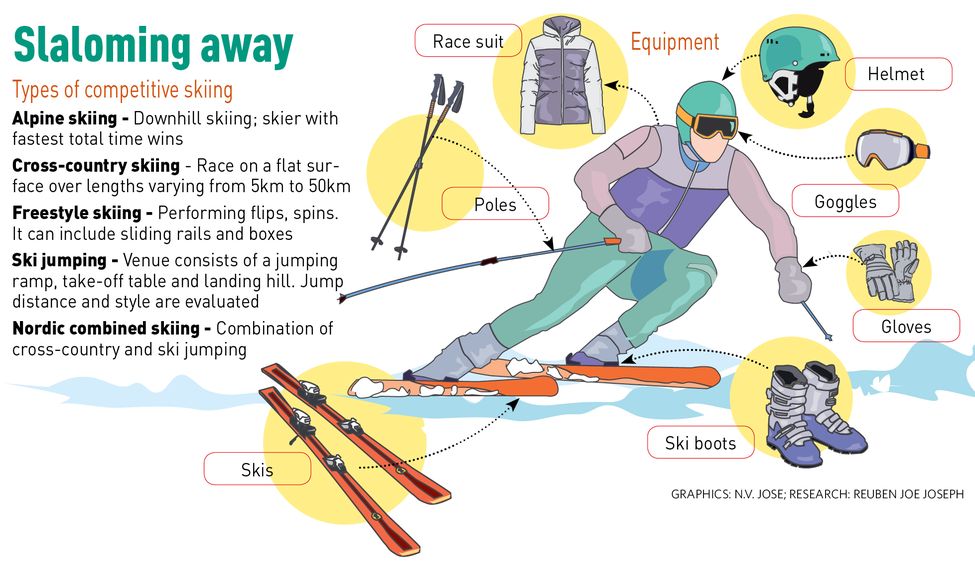

Aanchal says skiers need to be sponsored by the government, instead of the FIS. “We need equipment such as skis, ski boots, gloves, helmet, goggles, socks and waxing kits. Also, the government needs to understand that it needs to keep ready at least 10 people, not just one, to win medals,” says Aanchal.

Getting a ski resort would be a big help, according to Hira Lal. “Moreover, it would be nice if winners of international championships are offered jobs, because an athlete’s life is for barely four to six years. After all, you cannot play all your life.” Thakur, too, dreams about converting Manali into a winter resort of international standards. “We get 35,000 tourists a day. Almost 99 per cent of them are crazy about snow, and they just want to touch snow and it’s paisa vasool for them,” he says. “If we can convert this craze into winter tourism, we can achieve a great deal, like countries such as Austria, which are so heavily dependent on skiing.”

Two years ago, the president of one of Austria’s biggest skiing resorts stayed with Thakur for a week. “After surveying the place, he gave a preliminary report saying we had everything required. All that we needed to develop are some basic facilities, which would set the ball rolling for some great winter and adventure tourism.”