Three widows, two daughters and an overwhelming sense of grief occupy the house of the Palwes in Kekat Jalgaon in Paithan, Aurangabad. The house lost all its men―there were three―in the past three years. The Palwe widows, Yashoda, Chandrabhaga and Lakshmibai, and Yashoda's two daughters, Suman, 8, and Sarita, 6, live in a hut without an electricity connection. Even if it had a connection, it would not have been of much use, as the village seldom has supply.

The sun had set and the village was being enveloped by darkness when Sarita whispered: “Mother, I am hungry.” All that Yashoda could do was hug her tightly and cover her mouth. In the dim flickering light of the small kerosene lantern, the vacant stare of the girls was heartrending.

Nanasaheb Palwe, Yashoda's husband, committed suicide last November after the drought, which was the fourth in as many years. His father, Karbhari Palwe, had committed suicide two years earlier and his brother, Dagadu Palwe, had died of some ailment. Yashoda said Nanasaheb had borrowed money from private lenders to pay the labourers who had dug a well under the National Rural Employment Guarantee scheme. “The well didn’t yield water and he did not get the NREGA payment,” she said. Fearing the moneylenders, he committed suicide. Yashoda did not get any compensation from the government because the money was not borrowed from a bank―Nanasaheb’s suicide was treated as 'ineligible'.

Another widow, Kantabai Bankar, 45, lives just opposite the Palwes' hut. Her husband, Hanumant Bankar, hanged himself on a tree in January. He had borrowed money from private lenders to dig a well. His suicide also was 'ineligible' for compensation. “My two sons and I together earn Rs150 a day,” she said. “I don’t know how long we will live.”

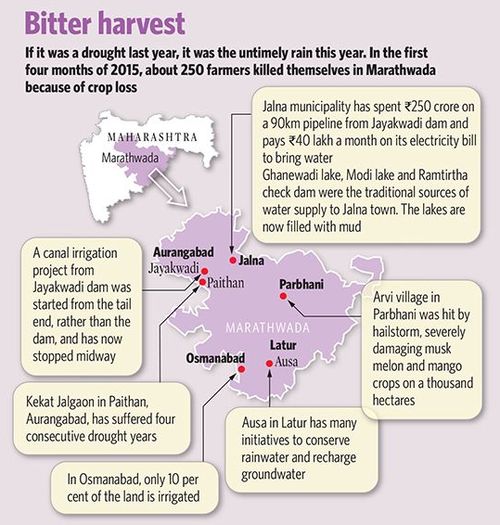

Droughts, hailstorms, untimely rain, lack of irrigation, manmade disasters, corrupt officials, water mafias―there are multiple dimensions to the agrarian crisis in Marathwada. In the first four months of this year, 255 farmers in the region killed themselves. Marathwada had one of the worst droughts in its history last year, and it was lashed by untimely rain and hailstorm in the first four months of 2015. Farmers who had saved some crops in 2014 lost everything in these four months.

“We have been the worst affected and the most neglected,” said Jayaji Suryavanshi, a farmer and activist in Aurangabad. “Despite the claims by the government, no compensation for the untimely rain and hailstorm has reached us.” He said the terms and conditions for compensating farmers for the crop losses and for suicides were beyond comprehension. “We have the least percentage of irrigated land, and politicians from western and northern Maharashtra do not let us get water,” he said.

Even those who had borrowed from banks are not any better off. Omprakash Jawale, 36, of Adgaon Jawle village in Aurangabad, consumed pesticide on March 28. He had planted 600 citrus and sweet lemon trees on two acres, and jowar and cotton on half an acre each. He had borrowed Rs4 lakh from State Bank of Hyderabad to lay a pipeline from a check dam 4km away and sold his house for Rs1.5 lakh to dig a well to store the water from the pipeline. “The well and the check dam dried up and there was hardly any rain. All 600 trees and the crop dried. We were expecting a profit of Rs2.5 lakh,” said Atmaram Jawale, Omprakash's father.

Jayakwadi dam, the largest in Marathwada, is just about 40km from Adgaon Jawle. Work on a Rs220-crore canal irrigation project linked to the dam had started a few years ago. But it was started from the tail end and the work stopped midway. “Had they started making the canal from the dam side, at least 30 villages would have got the water. Now all 70 villages along the canal are dry and thirsty,” said Suryavanshi.

Jalna, a municipality of three lakh people, has spent Rs250 crore on a 90km pipeline from Jayakwadi dam and pays Rs40 lakh a month on electricity bill to pump water for an hour on alternate days. The water shortage is attributed to a lobby in the town. “Jalna has 18 water bottling companies. They have drilled bores to 700 feet deep and ordinary people face severe shortage of water,” said journalist Krishna Tidke.

Ghanewadi lake, Modi lake and Ramtirtha check dam were the traditional sources of water supply to the town for more than 60 years. The lakes are now filled with mud. “Siddhi Vinayak Trust had donated money through the chief minister’s fund to clean these lakes. Ramtirtha check dam was cleaned in 2012, which consequently recharged nearly 3,000 bore wells in the nearby area,” said Tidke.

But the two lakes are still unattended. “Immediately after cleaning the check dam, the water companies bribed officials of the municipality and the irrigation department to not start the cleaning work of the lakes,” said Dhanling Suryavanshi, an activist.

Dnyanoba Pardhe, 45, used his wisdom and knowledge gained from his grandfather to seal his farm with one-foot-high mud dikes and dig small canals from all sides to two wells | Amey Mansabdar

Dnyanoba Pardhe, 45, used his wisdom and knowledge gained from his grandfather to seal his farm with one-foot-high mud dikes and dig small canals from all sides to two wells | Amey Mansabdar

Shah Nawaz, owner of Gemini, one of the oldest water bottling companies in Jalna, has no qualms about admitting that at least ten companies illegally pump water from bore wells drilled 700 feet deep or more. “Legally, we can’t drill below 180 feet; but everybody does it,” he said. It was already 43 degrees Celsius in Jalna, but he wanted the temperature to go up. “Our business suffers when weather is cold and cloudy,” he said. “We suffered badly during the first three months but now it has picked up. I pray that clouds do not come again.”

On the 110km stretch from Jalna to Parbhani, there is not a single patch of agriculture land. Hundreds of blue plastic drums were lined up along the road outside villages. Occasionally, water tankers would come and fill them. Parbhani also has had its share of suicides. Vasant Babar, one of them, hanged himself on a mango tree. The 60-year-old farmer from Sur Pimpri had eight acres where he produced soybean and cotton. He had borrowed Rs45,000 from a society, but lost his entire crop in the drought. Now his two sons work on farms for daily wages in Kolhapur.

“My brother and I are illiterate and don’t know anything but farming,” said Angad, Vasant’s son. His family, he said, ate only on alternate days, as they were not eligible for a below-poverty line ration card because they held more than five acres. “We got Rs1 lakh compensation―Rs30,000 by cheque and Rs70,000 in five-year postal fixed deposit. The chief minister came to our village, but he did not visit us,” said Angad.

A few kilometres from Sur Pimpri village, however, a farmer has found a way to beat the weather. In Bab-hulgaon, Dnyanoba Pardhe, 45, used his wisdom and knowledge gained from his grandfather to seal his farm with one-foot-high mud dikes and dig small canals from all sides to two wells. This helped him save every drop of rainwater. “The agriculture department also helped me. I have been growing bananas, mangoes, sweet lemons and vegetables throughout the year since 2009,” he said.

Pardhe has a net house on half an acre where he produces capsicum. He is building a bigger one on two acres for growing tomatoes. “My son helps me with the SMS services offered by meteorology department and Reuters. I plan my crops accordingly,” he said. Ten other farmers in his village have started following the methods to save water and recharge wells.

Apart from Pardhe's efforts, the projects in Ausa, Latur are the only worthwhile initiatives in Marathwada to conserve rainwater and recharge groundwater. Eighteen villages in Ausa have implemented these initiatives. But they learned the lesson the hard way. Nanasaheb Kadam, 62, a farmer in Selu village, had drilled 28 bore wells on his 18 acres. “I have three bores of 700ft. I spent Rs8 lakh for them, but all are dry,” he said.

The water conservation projects are jointly funded by the government and people. “Farmer leader Pasha Patel got Rs5 lakh from Sanjay Kakade’s MP fund, villagers contributed Rs25 lakh and district collector gave Rs30 lakh,” said Atrinandan Patil, a farmer. He had drilled 13 bore wells on his eight acres. He contributed Rs1 lakh to the water conservation project. “I could do that because my son is a chartered accountant and I am not entirely dependent on agricultural income,” he said.

Precious drop: Villagers in Parbhani keep drums on the roadside. Occasionally, water tankers come and fill them up | Amey Mansabdar

Precious drop: Villagers in Parbhani keep drums on the roadside. Occasionally, water tankers come and fill them up | Amey Mansabdar

Patel attributed the current situation to unsustainable farming methods. “We have paid heavily for pumping out every available drop of water.” he said. “Villages like Matola used to produce 70,000 tonnes of sugarcane a year, but we have not been producing even a kilo in the last 3-4 years.”

It is not just the blind weather that the farmers have to deal with. “A transformer installed on my farm burnt out; an officer asked for Rs15,000 as bribe to fix it. I couldn’t pay the money, he did not replace the transformer and my almost-ready crops on eleven acres died,” said Devidas Madke, a farmer in Moha village.

Few farmers in Osmanabad now grow sugarcane. “Western Maha-rashtra has more than 90 per cent irrigated land and we have less than 10 per cent,” said Nanasaheb Patil, 63, a farmer and activist. “It is unfair to ask us not to grow sugarcane because the government had not done irrigation here. Do they want us to remain poor by growing only low-value crops? Leaders from western Maharashtra want this region to be a desert because they need labour from here.”