Why did Congress vice president Rahul Gandhi choose eastern districts of Uttar Pradesh to launch his mega campaign for 2017 assembly polls? Why did his mother and party president Sonia Gandhi, too, pick Varanasi, in eastern Uttar Pradesh, to hold a road show a couple of months ago to kick-start the Congress campaign?

What compelled the Congress to paradrop former Delhi chief minister Sheila Dikshit in Uttar Pradesh and declare her the chief ministerial candidate?

What pushed the traditionally pro-dalit Bahujan Samaj Party to expel its dalit leader Sanjay Bharti in June for posting anti-Brahmin comments on Facebook?

What made Chief Minister Akhilesh Yadav of the allegedly pro-Muslim Samajwadi Party declare Parashuram Jayanti a public holiday?

Why is the BJP downplaying its new-found dalit card in certain parts of the state?

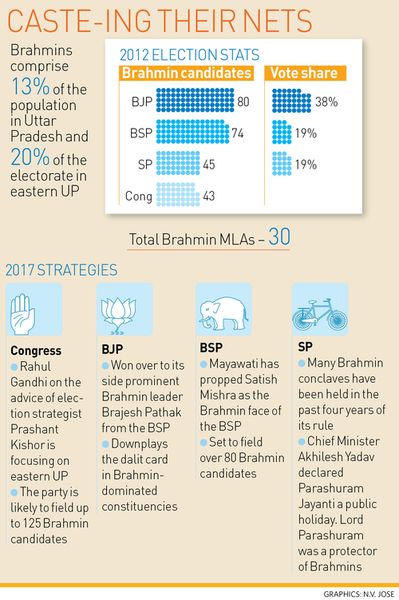

All these questions lead to one answer: the Brahmin vote. The four major political parties in Uttar Pradesh—the Congress, the BJP, the BSP and the Samajwadi Party—are vying to woo the Brahmin community to better their political fortunes in the 2017 polls.

Brahmins—who constitute about 13 per cent of the state’s population—play a crucial role in about 20 parliamentary seats, especially in eastern UP. In fact, all parties organise Brahmin sammelans ahead of elections in this region, where about 20 per cent of the electorate is Brahmin.

The Congress was the early bird. Its first move was to project Sheila Dikshit, a Brahmin, as the chief ministerial candidate. Then, it outsourced its poll campaign to political strategist Prashant Kishor aka PK, a Brahmin who had worked wonders for Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar.

PK believes Brahmins make a natural ally of the Congress and, by consolidating their votes, the party can regain its lost glory in Uttar Pradesh. Thus, the Congress carefully chose Rahul’s road show destinations. In the first leg, he visited many eastern districts of Uttar Pradesh, such as Deoria, Gorakhpur, Gazipur and Azamgarh.

His visit to Ayodhya—after 26 years by any member of the Nehru-Gandhi family—was also a well-planned move. Ayodhya, Varanasi and Allahabad are the sacred cities for Hindus and are regarded as Brahmin strongholds.

At a couple of meetings which PK held with the state Congress leaders, a loud and clear message was sent out: “Go all out to get the Brahmin votes.”

The Congress’s hopes are based on the fact that, in the 2009 general election, when Brahmins sided with the party, it won 21 of 80 Lok Sabha seats in Uttar Pradesh. Congress insiders say the party is likely to field 100 to 125 Brahmin candidates in the assembly election.

“When the Brahmins were with the Congress, it was strong at the national and state levels,” says Rahul Mishra, a Brahmin lawyer from Amethi. “In older days, there were eight to ten Brahmin ministers in the cabinet. Gradually, however, the community started drifting away from the Congress. The party has not made much efforts to bring the state’s Brahmins forward. The experiment of bringing them forward should begin from Amethi [which is Rahul Gandhi’s parliamentary constituency].”

The BSP realised the importance of Brahmin votes in 2007, when its leader Mayawati embraced the upper castes and returned to power, proving predictions wrong.

The shift in the BSP’s stance was a major turnabout—from “Tilak, tarazu aur talwar, inko maro jute chaar (beat the Brahmins, Baniyas and Thakurs with footwear)” to its 2007 slogan “Brahmin shankh bajayega, haathi badta jayega (as the Brahmin blows the conch, the elephant, the BSP’s symbol, will keep marching ahead)”.

Mayawati fielded 89 Brahmin candidates in the assembly election in 2007 and 74 Brahmins in 2012. But the neglect of the community under her rule alienated it from the BSP. Also, many Brahmins alleged that they were being persecuted using the Scheduled Castes/Schedule Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act.

Hence, the BSP’s tally in 2012 plummeted from 206 to 80. In 2013, Mayawati formed Brahmin Bhaichara Samitis (brotherhood committees) to patch up with the Brahmins.

In the 2014 Lok Sabha election, she fielded more Brahmins (21) and Muslim (17) candidates than dalits. All of them lost in the Modi wave. But Mayawati can take heart from the subsequent Bihar and Delhi elections, which showed that the Modi wave did not sway assembly polls.

Mayawati deployed Satish Mishra and Brajesh Pathak (who later joined the BJP), as well as local-level Brahmin leaders to win over the community. And this time, too, the BSP is likely to field a large number of Brahmin candidates.

The ruling Samajwadi Party also has taken several steps to win over the Brahmins, such as declaring Parashuram Jayanti a public holiday, assuring withdrawal of false cases against Brahmins under the SC/ST act, and holding Brahmin conclaves.

At one such conclave, Chief Minister Akhilesh Yadav said, “With your (Brahmins) support, our party won majority in the assembly polls. We want your support in the future, too, so that the party can deliver better results.”

Loud and clear: Tara Chand Pandey, a Brahmin, performing puja at his house in Lucknow. The community members are disgruntled over political parties remembering it only during election time, and is likely to vote for the party that lists solid schemes on its manifesto | Pawan Kumar

Loud and clear: Tara Chand Pandey, a Brahmin, performing puja at his house in Lucknow. The community members are disgruntled over political parties remembering it only during election time, and is likely to vote for the party that lists solid schemes on its manifesto | Pawan Kumar

In the 2012 assembly election, 21 of Samajwadi Party’s 45 Brahmin candidates had won.

Jai Shankar Pandey, a prominent Brahmin leader of the Samajwadi Party in Faizabad (Ayodhya), says, “This community is very flexible. Socialist leader Ram Manohar Lohia used to say that, in politics, the Brahmins should act like manure, with which the have-nots and the downtrodden could bloom. Such was the potential of this community, but, in today’s politics, the parties have neglected it.”

The BJP enjoys solid support from the Brahmins. Its state unit, until recently, was headed by Laxmikant Bajpai, a Brahmin. In April this year, backward caste leader Keshav Prasasd Maurya replaced him.

The BJP certainly does not want its Brahmin vote bank to erode. Thus, it has been downplaying its dalit card in Brahmin-dominated constituencies.

The party has also not projected a chief ministerial candidate. In the BJP circles, it is said if the party president is from a backward community, the chief ministerial candidate would be from an upper caste, more likely a Brahmin.

In 2012 assembly election, the BJP, which had fielded 80 Brahmin candidates, remained the most favoured party of the community, bagging 38 per cent of its votes. There, however, was a vote share dip of 6 per cent, compared with the 2007 assembly election.

“Traditionally, the Brahmins have been with the BJP and they still vote for the BJP in large numbers. So there is no harm in the party wooing the community,” says senior BJP spokesperson Manoj Mishra (who is a Brahmin).

“Brahmins have always enjoyed the prospect of gaining political prominence,” says Vinod Pandey, a Brahmin in Lucknow. “The party that is able to drive home the point that Brahmins are serious players in the 2017 election will win a good number of seats.”