It was 15 years ago, and she was just 19 years old. But Bilkis Bano still remembers every moment of that horrifying day. She saw 14 members of her family, including her three-and-a-half-year-old daughter, mother and two sisters, being butchered by a rioting mob near Randhikpur village in Dahod in Gujarat. That she was five months pregnant did not stop them from gang-raping her. They left her unconscious, thinking she would die.

She lived to tell her story, and did not buckle under pressure to stop seeking justice. “There has not been a single day when I did not remember that ill-fated day. I try to keep myself busy,” she told THE WEEK, at an activist friend’s house in Delhi.

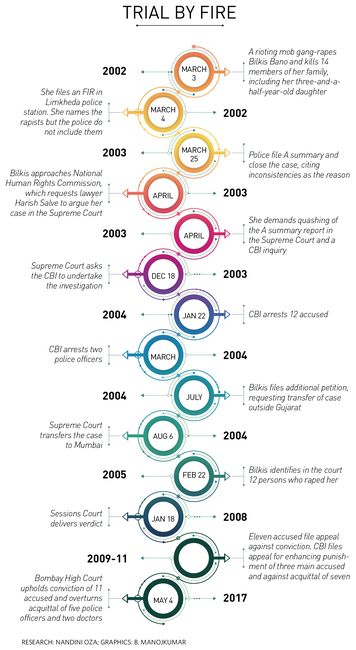

Bilkis, her husband, Yakub, and their five children have been like nomads all these years, changing their house every now and then. On May 4, the Mumbai High Court upheld the conviction of 11 men found guilty of raping her and murdering others, and overturned acquittal of five police officers and two doctors. The policemen and doctors have been charged for tampering with evidence.

“I want to start life afresh,” said Bilkis. The judgment has restored her faith in the judiciary. She was all the more happy about the High Court charging the police officers and doctors. But she does not want to take revenge. “I do not want life for life. I want that they get the stringent of punishments and languish in jail and remember what wrong they did to me and my family,” she said.

Rage of the crowd: A mob runs down a street in Ahmedabad during the post-Godhra riots in 2002 | AFP

Rage of the crowd: A mob runs down a street in Ahmedabad during the post-Godhra riots in 2002 | AFP

About 1,000 people, mostly Muslims, were killed in riots in Gujarat, after a coach of the Sabarmati Express was torched by a mob in Godhra, killing 59 passengers (most of them karsevaks returning from Ayodhya), on February 27, 2002. Bilkis and some members of the family tried to escape from the riot-affected Randhikpur village but were intercepted by a mob. The women were in tribal attire, hoping that nobody would identify them. But the attackers knew them personally. “I used to address the attackers’ fathers as chacha and mama,” she said, holding back tears.

They snatched her daughter from her and banged the child on a rock. They killed everyone on the truck and gang-raped her. And they left her to die. Hours later, though thirsty and hungry, she climbed a hillock and took shelter in a small cave. Later, when she got down to drink water from a hand pump, she saw a police vehicle and got into it.

The threats started right at the police station. “Bilkis was threatened that she would be given a poison injection if she revealed the names of the attackers,” said Yakub, who found her a fortnight later at a relief camp. Yakub and her father and brother survived because they did not leave Randhikpur with the family. “We kept receiving threats. But I did not let this information go to Bilkis or else she would break down,” said Yakub. The threats ranged from “We will see her” to “We will purify the village and not allow Muslims to stay”.

Bilkis has been to Randhikpur only once after the incident, to meet some relatives. She broke down like a child. “I will never forgive the culprits,” she said. “My mother and sisters are no more. They took away their lives.”

Her eldest daughter, born in 2002, wants to become a lawyer. “She says she wants to help the community,” said Bilkis. Two of her daughters have been part of her struggle as the couple took them to hearings and interactions in Mumbai and elsewhere. “We do not discuss the issue. However, children are aware about what their mother had gone through and what was done to the community,” said Yakub.

The children’s education has suffered because of the constant movement of the family. “Every time a new admission is taken, we try not to make our names obvious,” said Yakub. Bilkis’s name has never been given.

Probably, Bilkis will now be able to get over the nightmares that haunted her for years, but the traumatic memories will die only with her. “She would get up in the night and shout,” said Gagan Sethi of Jan Vikas, an Ahmedabad-based non-profit organisation. “There were times when she would say ‘if I smile people would feel as if nothing had happened to me’,” said Sethi.

Yakub said they would not have got justice if the case was tried in Gujarat. Activists from all over the country, who have helped her in the case, had their own mechanisms to keep a watch without affecting her privacy.

Sethi fears that, now that the policemen and doctors have been indicted, it is not safe at the local level. Nonetheless, he said, that the Mumbai High Court verdict had proved that there was a difference between the state and the nation and there was a judiciary that was separate and independent.

Sethi said Bilkis had not been given the compensation meant for rape survivors. The state had announced a compensation of Rs 5 lakh but the Supreme Court had increased it to Rs 10 lakh. “It is not something that we should ask for,” he said.

Yakub had a small-time cattle business. In between he tried to run a grocery store. Now he is back to the cattle business but it is not doing that well because they keep moving from one place to another.

The activists and friends who support Bilkis often say she has a steely resolve. And she acknowledges Yakub’s support in her journey. Not even once did she fear that he would leave her. “I had faith in him. Family members also supported,” she said. “It was no fault of Bilkis,” said Yakub. “It was an attack on the community. They did not attack her. There could have been someone else if she was not there.”

Bilkis tries to make her life as normal as possible. She did not have a formal education, but she learned to read Hindi during the trial. She cooks for her family and watches television with her children. She gets irritated when someone asks questions comparing what happened to her and to the woman who was raped and tortured in a bus in Delhi in 2012. “There is steel in her,” said her activist friend. “Her shutting up says a lot.”