Paris’s agonising evening is turning into a security nightmare. In a few days, about 120 presidents and prime ministers, thousands of delegates, 3,000 journalists and more than 20,000 environmental activists—they include a few anarchists—will arrive in Paris to meet at Le Bourget Parc d’Espositions, 10 miles from the city, and discuss climate change and the future of the earth.

Securing the 120-odd VVIPs is the least of the French authorities’ worries. “Security at UN climate conferences is always tight,” said UN Climate Change Secretariat spokesperson Nick Nuttall. “But, understandably, it will be even tighter for Paris.” VIP movement will be tightly controlled and the spots where they converge will be tightly secured. “Paris has hosted several summits; the authorities here know how to handle summit security,” said an Indian diplomat. “The worry is about the others whose movement cannot be regulated.”

Already, the press and NGO accreditations have been closed—well before the announced deadlines. Yet, border control officials and intelligence officers are not sure if any of the murder-minded ones has already obtained visa in the guise of a mediaman or an environment activist.

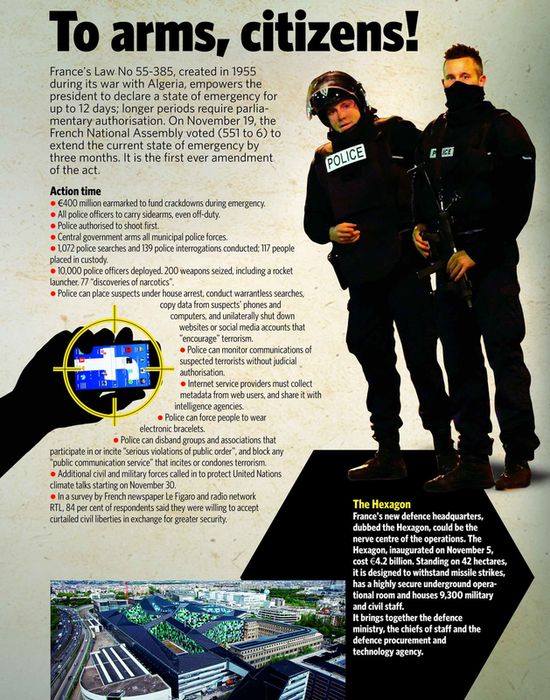

On President Francois Hollande’s request, the French parliament has passed laws that would enable authorities to intercept communications, raid houses without notice any time of the day or night, and even without a warrant, for the next three months. Hollande has permitted the police to hire 5,000 more officers, 2,500 judicial investigators and 1,000 customs officers. But all these will take time, say security experts. “These measures will be operational in five years’ time,” Bernard Squarcini, former chief of France’s intelligence agency, has been quoted in the French media. “In the meantime, what do we do?”

Even after the summit, France will need to be vigilant. At least 20,000 more troops will have to be mobilised so as to keep 10,000 more on constant patrolling and guard duties in the next few months. Hollande is also deferring an earlier announced plan to cut the military’s strength by 2.3 lakh. Defence spending will be hiked from 3.8 billion euros to 4 billion euros.

Identifying the threat as having emanated from the caliphate of terror styling itself as Islamic State or Daesh which holds territory in parts of Syria and Iraq, Hollande has despatched 12 fighter jets to strike at its military targets. Aircraft-carrier Charles de Gaulle was despatched from Toulon to patrol the eastern Mediterranean, and there could be further strikes by the 20 carrier-based aircraft. The air force claims to have taken out a few tactical targets, but has failed to explain the significance of the targets to the French public. After about a week of starting the military action, armed forces chief Pierre de Villiers admitted candidly: “There will be no military victory against Daesh in the short term. In the military, we are used to the long term, but people want fast results. In Syria and Iraq, we are in the heart of that paradox. Everybody knows that in the end this conflict will be resolved through diplomatic and political channels.”

The problem is that France does not have the military capability to engage in a prolonged war in distant lands, let alone to defeat the enemy and hold the territory that he now holds. The country is already engaged in three wars. In Operation Sentinel, about 10,000 troops are guarding sensitive targets, especially synagogues, churches and mosques since the Charlie Hebdo attacks of January 2015. Another 3,000 troops are deployed in the anti-terrorism Operation Barkhane spread across France’s five former African colonies, Mali, Mauritania, Burkina Faso, Niger and Chad. Now another 1,000 are engaged in the current operations in Syria and Iraq, though no ground troops are involved. According to de Villiers, some 34,000 soldiers are currently deployed in France and abroad on active duty.

The French economy also would not be able to sustain more operations. By declaring that “France is at war” Hollande is hoping to invoke a clause in the European Union defence protocol which obliges other member-states to provide military aid in the event of a member-state being attacked by an outside enemy. But, given the recent euro crisis fomented by a budget crisis in Greece, it is doubtful how much the others, save perhaps Germany, can commit. And, a German domination of the European Union has been what France and Britain have been resisting.

For the time being, the terrorist attacks have helped bring the mutually squabbling European states together. Many had even thought that the European Union was on the verge of a break-up. Economists have been predicting a return of the debt crisis, and there were fears that Portugal and Britain might walk out of the union by next year. France, faced with economic stagnation and joblessness, and led by socialist Hollande, has been resisting economic reforms that the European central bank was asking for.

So, to prosecute the war, France needs stronger-armed and stronger-willed allies than any of the fellow-Europeans. There are two, the US and Russia, and they have been launching air strikes on Islamic State targets, but the two are building their own coalitions and pulling in opposite directions. The US believes that President Bashar el-Assad of Syria is the fountainhead of all the evil in the west Asian region and needs to be eliminated, whereas Russia believes that he is the last guarantor of stability in the region and needs to protected and promoted.

In other words, while Obama believes that Assad is the problem in the region, Putin thinks that Assad is part of the solution. While Saudi Arabia and Turkey agree with the US, and have been funding and arming the anti-Assad rebels in Syria, Iran and Russia have been arming Assad and helping him put down the rebels. Both camps have been wooing France after the November 13 attacks and France can’t decide who to join. The tussle reached the stage of a flare-up last Tuesday when a Turkish F-16 shot down a Russian Sukhoi-24, alleging that it had strayed deliberately into Turkish airspace, whereas Russia claimed that their plane had stayed in Syrian airspace, pounding at IS targets.

France had been following the US line, particularly in the wake of the Crimean conflict. Last year, France cancelled a Russian order for four Mistral helicopter carriers—and thus lost 1.2 billion euros—protesting against Putin’s militarism against Ukraine over Crimea. But, in the middle east, France was a little more ambivalent. Though France had, along with the US, the UK, Germany, Turkey and Saudi Arabia, denounced Russian jets targeting the Syrian rebels, Hollande is now said to be having second thoughts.

“We have followed a certain path since the Crimean conflict and the sale of Mistrals,” said Brigadier-General Jean-Vincent Brisset, research director at the International Relations and Strategy Institute, indicating that it might change. The strongest signal about a French change of mind has been the post-November 13 tactical military collaboration between the Russian and the French air forces in striking at IS targets in Raqqa. Encouraged, Putin has despatched a detachment of warships into the Mediterranean to team up with the French carrier, Charles de Gaulle.

All the same, the French are being careful not to be taken into a close Russian strategic embrace. Even after speaking to Russian military general staff on phone, de Villiers denied that there was “at this stage any coordination of strikes or identification of targets in consultation with the Russians, even if we have the same enemy, Daesh.”

But the Russians are at their persuasive best. As if to demonstrate that he would back his words with fire, Putin also ordered cruise missile attacks on IS targets in Raqqa—in a close copy of the US style of attacking continental targets with maritime firepower—within three days of the Paris attacks. The strikes almost looked like a follow-up volley immediately after half a squadron of French jets hit the same array of targets.

These signs of a Franco-Russian tie-up have unnerved Washington. Calling France America’s oldest ally (a reference to the services rendered by the legendary French general Marquis de Lafayette to George Washington in defeating the English army of Lord Cornwallis in the final battles of the American war of independence), Barack Obama dispatched not only Secretary of State John Kerry but also a clutch of influential senators like John McCain to Paris.

While the rest of the world sees France being caught in a cleft-stick situation, many in France believe that this could also be an opportunity for France to emerge again as the moderating force in the western coalition as it had during the Cold War. During the Cold War, France had always pursued a softer and more independent line from NATO, towards the eastern adversary. Now, French foreign ministry officials see a repeat of history. They point to Hollande’s trips to Washington and Moscow this week as part of an attempt to bring about a meeting of minds between the two. In his address to the French National Assembly, Hollande has called for a “large and singular coalition” among “all who can rally help to fight the terrorist army.”

French officials have even started claiming that their persuasion is working on the Russians. Five days after the Paris strikes, Defence Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian claimed that Russia had “shifted” its position in the middle east, and was now bombing IS targets and not just anti-Assad rebels.

The French also know that they cannot go the whole hog with the Russians. For one, the US and the western allies control most of the intelligence regarding the movement and activities of Islamic radicals not only in and out of the middle east but across Europe and even the rest of the world. Any attempt at neutralising the threat within French or European territory would need intensive and extensive intelligence sharing with the US and the rest of the western world.

And, then, there are the vestiges of the old colonies to worry about, as was demonstrated by the Mali attack a week later. The French military was involved in operations in Mali a year ago, and there still are more than 7,000 French citizens in Mali. Security experts in Paris view the attack on the hotel in Mali essentially as a follow-up attack on targets which hurt the French. The Americans still wield far higher influence in these regions than the Russians.

Thus a Russo-American rapprochement is what France desires; and that is what the world, too, desires.