This is no cock and bull story. It dates back to the Indus Valley civilisation. Picture this: a herd of cattle is grazing lazily, followed by herders, holding long sticks having a piece of white cloth at the end. Suddenly, a wild bull comes charging. A young herder chases the bull, hops on to its hump, holding it by its horns, and finally tames it. This becomes a regular affair.

Over a period of time, this taming of the bull became a sport—‘Eru Thazhuvuthal’ or embracing the bull—demonstrating heroism and valour. During the Nayak dynasty rule in the 16th-17th century, it came to be known as Jallikattu, as coins, called jalli or salli in Tamil, wrapped in a piece of cloth were tied (kattu) to the horns of the bulls. The bull tamer who untied the knot would get the coins as prize. Soon, the cloth tied to the horns was replaced with bright ribbons and the tamers were given trophies instead of coins.

As the sport became a tradition and acquired a cultural identity, villagers started rearing bulls exclusively for the sport and equated them with gods. That is why, during the Pongal festival, when the sport is usually held, the koyil kaalai (temple bull) is the first bull to come through the vaadi vasal (the entrance). It would have a free run on the ground as a mark of respect to the village and its deity.

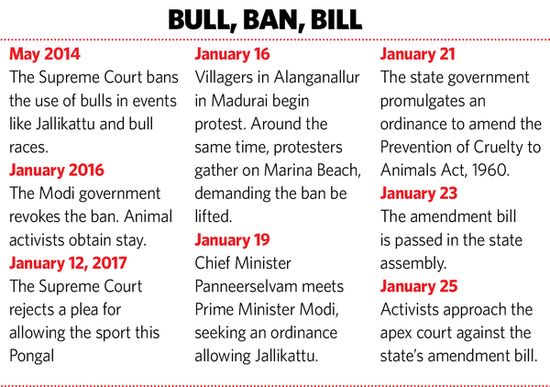

For decades, Jallikattu had a free run in Tamil Nadu. But in the last few years, the ancient sport has sparked a raging debate, with one side highlighting cruelty towards animals and danger to spectators, and the other upholding culture and tradition. A few days after Pongal this year, a few hundred people gathered on Chennai’s Marina Beach in support of Jallikattu and triggered a mass movement across the state within 24 hours. For nearly a week, the beach became home to protesters from all walks of life. They demanded that the 2014 Supreme Court ban on Jallikattu be lifted and the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960, be amended to exclude bulls from the list of performing animals. The police, too, encouraged the supporters, even as slogans against the Union government, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Tamil Nadu Chief Minister O. Panneerselvam and the ruling AIADMK rent the air. Schools and colleges were closed. Traders called for a day-long hartal.

The protests, though political in nature, had no political affiliations. Politicians were barred from the venue—from DMK leader M.K. Stalin to Pattali Makkal Katchi’s Dr Anbumani Ramadoss. But political leaders found ways to stay relevant. Panneerselvam called on Modi to discuss the protests and the possibility of issuing an ordinance to allow Jallikattu. A day later, AIADMK MPs went to Delhi, seeking an appointment with Modi. The prime minister did not meet them, and they instead met the president. In Tamil Nadu, the AIADMK’s new general secretary V.K. Sasikala extended her support to the movement. The DMK was out on the roads, engaging in rail roko, and raising slogans in favour of the protesters.

Finally on January 21, the state government promulgated an ordinance for conducting Jallikattu. Panneerselvam assured the people that the government would intro-duce a bill to replace the ordinance

in the current session of the assembly. But protesters refused to relent.

When Panneerselvam went to Alanganallur in his home district Madurai, where the sport first became popular, he was denied entry. Meanwhile, the protests turned violent. Roads were blocked and vehicles set on fire. And, the policemen turned their lathis on them.

The entire protest, say political observers, was instigated by the power centres within the AIADMK to defame Panneerselvam and to channel hatred against the Union government. “There were protests last year, too. We all saw Union minister Pon Radhakrishnan and others bat for Jallikattu last year. But the protests died down as usual. This time it reached a new high only because of the indirect support from unexpected circles,” said a senior journalist.

A lawyer saw the agitation as a tactical move by the Centre to make government enact a law. The PCA Act is a Central law. Since the Supreme Court had twice disallowed Jallikattu in 2014 and 2016 and owing to its adverse experience of ordinances, the Modi government did not want to take a chance, the lawyer said.

On January 23, the state government, with powers available under the concurrent list, chose to introduce a bill to amend the parent law. While tabling the bill in the assembly, Panneerselvam said, “With this bill all hurdles to Jallikattu have been removed.” The bill will become a law once the president approves it.

“All possible grounds of assault found in the PCA Act have been addressed in the state’s amendment bill,” said retired High Court Justice Hari Paranthaman. “It takes care of the list of prohibited animals part and specific exemptions for using bulls in Jallikattu. It also says using the bulls for jallikattu doesn’t amount to cruelty.”

The state bill inserted Section 2(dd) in the Central act to define Jallikattu as “an event involving bulls conducted with a view to follow tradition and culture”. It also added a provision to Section 3 to empower the state to frame rules for conduct of Jallikattu. Clause (f) inserted to section 11(3) of the act states that Jallikattu cannot cause cruelty to bulls.

The protests were called off. But the question is whether the bill will sustain judicial scrutiny. The DMK regime had brought in a Jallikattu regulation act in 2009, which was challenged by animal rights activists and later struck down by the Supreme Court in 2014. In 2016, activists challenged the court after the Union government’s circular allowing the use of bulls in Jallikattu. The Supreme Court stayed the notification. On January 25, activists moved the court against the state’s amendment bill. Looks like the Jallikattu controversy would rage on.