The brutal murder of a 15-year-old schoolgirl had unleashed massive protests across Maharashtra last year. The repercussions are felt even now. Her body was found on July 13 at Kopardi village in Ahmednagar district. She had been stripped and thrashed. Her arms were dislocated at the shoulders.

Kopardi lies in the drought-prone Karjat taluka. The village’s 470 homes have 2,200 people. Most residents belong to the Maratha caste, and a majority are from the Sudrik clan. She, too, was a Sudrik. Dalits have around 12 homes in the village. The accused—Jitendra alias Pappu Shinde, Santosh Bhawal and Nitin Bhailume—came from these homes. Two of them worked in a brick kiln owned by the victim’s cousins.

Once details of the crime hit headlines, rage spread across the state. Maratha youth poured out their anger on social media. Soon, politicians came calling at Kopardi. The rage led to consolidation of the Marathas, who form almost 38 per cent of the state’s population. Politicians were stunned when nearly three lakh Marathas came together for a silent rally in Aurangabad. They demanded a fast trial and death penalty for the accused. They also demanded reservation for Marathas and amendments to the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act.

The polarisation of the Marathas and the dalits took on scary proportions. “[There was] a lot of venom on social media. The 2016 Nashik riots were a result of this vicious polarisation and hatred,” said Vinay Kate, a dalit scholar.

The house of the victim’s grandparents | Niranjan Takle

The house of the victim’s grandparents | Niranjan Takle

Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis told the state assembly that special public prosecutor Ujjwal Nikam would handle the case. The government was banking on Nikam’s star value to douse the flame.

Eighty-nine days after the crime, the Ahmednagar district court heard the case. THE WEEK accessed copies of the first information report, the chargesheet, forensic reports and witness statements. Quite a few things didn’t add up. The following excerpt from the FIR has been edited for clarity:

The victim, who was studying in Class 9, was ill on July 12 and 13. So, she did not attend school. At 6:30pm on July 13, her mother asked her to fetch some spices from her grandparents’ house, around one kilometre from their house. The victim cycled over, placed the bag of spices on her bicycle carrier and started for home. The three accused allegedly stopped her beside an open field, around 150ft from her grandparents’ house. They assaulted her brutally, raped and murdered her. Then, they dragged her body for 150ft, across the road, to a field diagonally opposite her grandfather’s house. At this point, Shivram Gorakh Sudrik, 23, a cousin of the victim, spotted them.

Shivram’s statement says he saw Pappu Shinde standing near a neem tree between 7pm and 7:15pm. Shinde ran away when Shivram called out. Then, Shivram went to the tree and saw the victim lying there, naked and motionless. By then, the victim’s mother and elder sister, too, reached the spot. Shivram said he ran after Shinde, but the latter gave him the slip.

Carrying a burden: Babulal Shinde, father of accused Pappu Shinde | Niranjan Takle

Carrying a burden: Babulal Shinde, father of accused Pappu Shinde | Niranjan Takle

Lawyer Balasaheb Khopade, a Maratha, is walking a tightrope by representing Bhailume, the third accused. The retired public prosecutor voluntarily took up the case. “My inner voice asked me to take this up to save the grace of the Maratha community,” he said. The lack of evidence convinced him, he said.

“Shivram Sudrik does not even mention the presence of accused No 2 and No 3 in the complaint,” Khopade said. “This itself shows that everything was fabricated later to frame others.” The supplementary statement—filed on the same day as the complaint—also does not mention the other accused. It shows the incident happened between 6:45pm and 7:15pm. “So, it happened in just 30 minutes? The alleged abduction, assault, rape, murder and relocation of the body...?” asked Khopade.

THE WEEK visited the alleged crime site, near the house of Lalasaheb ‘Bapu’ Sudrik, the victim’s grandfather. “Her grandparents were at home, but they did not hear or see anything, although this entire stretch is an open field,” said Rekha Sudrik, the victim’s mother.

The contradictions in statements are stark. For example, Rekha deposed in court that her husband was working in a field when the murder happened. She told THE WEEK that he was at the hotel he runs—Hotel Garwa in Karjat.

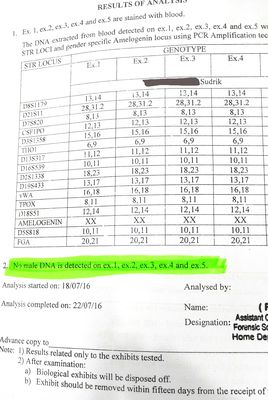

The forensic report, which says no male DNA was detected on exhibits from the crime scene.

The forensic report, which says no male DNA was detected on exhibits from the crime scene.

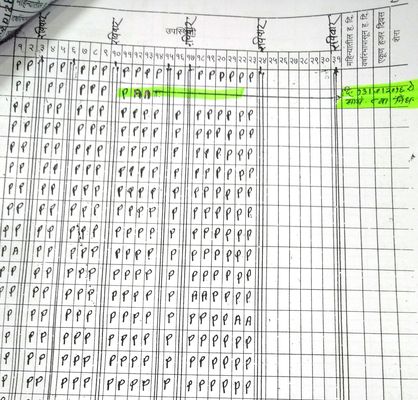

The attendance sheets of the victim’s class also threw up some questions. “I pointed out to the court that the page for June has ‘90’ printed on the top right, but there is no page number for July,” said Khopade. “And, the attendance markings on July 12 and 13 look like ‘P’ was overwritten to make it look like an ‘A’. The teacher denied the charge, but he did admit to writing: ‘Died at 8pm on the 13th July’. It is important to note that he even wrote the timing of her death. That’s why I called it fabricated evidence.”

The Karjat Police Station’s diary entry about the incident said: “Lalasaheb Sudrik of Kopardi village in Karjat taluka called at 9:40pm and said that someone had killed his 16-year-old granddaughter. And he hung up.” Khopade said, “The complainant and victim’s mother allegedly saw Pappu Shinde at 7.15pm. Why was the call made at 9.40pm and why did he say that ‘someone’ killed his daughter?”

THE WEEK has copies of the forensic reports and the postmortem report. “Surprisingly, the postmortem report mentions that Pappu Shinde killed the victim,” said Khopade. “Why did the doctor find it necessary to mention it?”

The forensic report also mentions that the jaw patterns of accused 2 and 3 do not match with the bite marks on the victim’s body. The forensic department did not find vaginal fluid on the clothes of the accused. It also said that there was “no trace of semen”. The reports also mentioned that “no male DNA was detected” on exhibits provided from the body and the crime scene.

Prosecution witnesses talked of having seen the accused on a new, blue TVS motorcycle on July 13. It was allegedly parked close to the crime scene. A few witnesses said that Shinde bought the bike three days before the crime. Laxmibai Sudrik, the victim’s grandmother, said: “A grandson of our cousin had lent Rs 80,000 to Pappu Shinde to buy the bike as he was working in his brick kiln.” THE WEEK has a copy of the invoice of the bike, dated July 14, a day after the crime, which said the bike was sold to Shinde. Form 20—a prescribed regional transport office form for registering a vehicle—had signatures of Shinde, but did not mention the engine and the chassis number, a mandatory requirement for registering any vehicle. Khopade said, “A daily-wage labourer working in a seasonal brick kiln gets a hand loan to buy a bike. The bike gets sold to him one day after the crime date. This is fabrication.”

The victim’s school attendance sheet. Defence lawyer Balasaheb Khopade says the Ps (present) for July 12 and 13 have been altered to look like As (absent).

The victim’s school attendance sheet. Defence lawyer Balasaheb Khopade says the Ps (present) for July 12 and 13 have been altered to look like As (absent).

THE WEEK also met Babulal Shinde, father of Pappu Shinde, in Shedgaon village. “I had gone to Pandharpur Yatra and my wife, daughter-in-law and Pappu were at home,” he said. Pappu, he said, used to have liquor at Bapu Sudrik’s place, and was friendly with the girl. “Pappu has told us that he was drinking in Bapu Sudrik’s open yard when he heard the wailing and shouting. He got scared, started running in the drunken state and fell down a few times. But, he doesn’t remember anything after that,” said Babulal.

He added that Santosh Bhawal, accused no 2, used to live in the brick kiln itself and never joined Pappu for drinking, while Nitin Bhailume, accused no 3 and their relative, had gone out and barely returned to their house when Sudrik’s men came and started beating him. “I don’t know who really killed the girl, but innocents shouldn’t be made scapegoats,” said Babulal.

When asked about the case, prosecutor Ujjwal Nikam told THE WEEK: “The trial is going on. I will be closing my examination of witnesses soon. The investigation officer’s witness statement is to be recorded. The defence also has a list of witnesses to examine. So far, this is the status.”

THE WEEK also talked to P.B. Sawant, former Supreme Court judge, who said, “I don’t think such evidence will stand the trial.”

The issue, meanwhile, has become highly sensitive. Four Maratha youths from Beed district tried to attack the accused on court premises on one of the trial dates in April. The accused and their families live in fear, while the Marathas are anxious to see the accused get capital punishment.