Jyothi Reddy still remembers yearning for the puris and aloo curry at a shop on her way to school. She could never afford it. “That smell is still in my memory,” she says, with a laugh. “Now, when I can buy as many puris as I want from the best of restaurants, I am avoiding oil!”

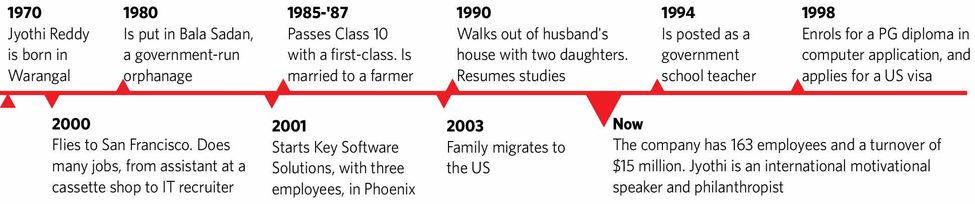

Jyothi Reddy’s life is a story of turnarounds. It is a story of turning adversity on its head. Once a farmhand in a small village in Warangal in undivided Andhra Pradesh, she is now CEO of Key Software Solutions, Phoenix, USA.

With five mouths to feed, her parents, Venkat Reddy and Saraswathi, kept their sons at home in Warangal and sent the daughters to the government-run Bala Sadan orphanage.

Her younger sister, Lakshmi, ran back home. “If I, too, had returned home, my father would have harassed my mother,” says Jyothi.

Her five years in the orphanage were nightmarish. There were sleepless nights and food-less days. Lying on the ground gave her bad bouts of skin rashes. And the frequent sighting of worms in the daily rava upma nauseated her.

The only memories she cherishes are magician Samala Venu’s visits on Children's Day. “He would give us chocolates and blankets,” recalls Jyothi. “I used to think that, I, too, would someday give chocolates to orphan children.” Now she celebrates Children's Day and her birthdays sharing a 100kg cake at orphanages.

Jyothi never met her parents during her five years at the orphanage. During summer holidays, she would stay at the superintendent Vatsala Devi’s house and help her with household chores. “She took good care of me, and I used to call her ‘amma’. Her daughter was a doctor, and I, too, wanted to be known as Dr Jyothi Reddy,” she says. “Now, I have registered to do a PhD on women's empowerment in rural areas. I might still realise my dream!”

She passed Class 10 with a first class, and returned home in 1985. A rude jolt awaited her. Her father had fixed her marriage to Sami Reddy, a farmer, who was 10 years older than her.

“I got married on March 3, 1985, and had my first daughter, Bina, on the same date next year, and then Bindu on the same date in 1987,” says Jyothi.

She did farm labour on her husband's two acres, but was not allowed to sell even “a handful of the groundnuts” she harvested. So, she worked on another farm, too, for a daily wage of Rs5. “I was just 18, and there were times when I did not have even 25 paise to buy milk for my girls,” she says. “I used to sell empty liquor bottles at 5 paise each to buy milk.”

By 1988, Jyothi was depressed.

She once walked towards an open well with her elder daughter. Fortunately, the younger girl's wailing pulled her back.

She was also attracted to Naxalism, which was at its peak in that region during that time. “I wanted to take revenge on the unjust system,” she says. But, again, the thought of her children pulled her back.

Then came the turning point. Jyothi landed a job as an adult education teacher at the Nehru Yuva Kendra, on a monthly pay of Rs120. Then she joined another project as a National Service Volunteer, for Rs190 a month.

“At times, I had to travel by even lorries to reach home. But, whenever I reached home a little late, I would be grilled. I used to wonder why I had to answer the stupid questions when I had been struggling to feed my daughters,” she says.

In 1990, Jyothi walked out of the house with her children. All she had was Rs110 clutched in her palm and a few utensils and clothes in a shoulder bag. She went to Hanamkonda on the outskirts of Warangal, and rented a room for Rs60 a month.

A friend, who ran a tailoring shop, offered to pay her one rupee for stitching a petticoat. “I stitched about 15 pieces a day,” she says.

She resumed studies through the B.R. Ambedkar Open University.After graduation, Jyothi got posted as a special teacher in Ameenpeta village, a two-hour train ride from Warangal. While the salary was $398, she had to spend nearly Rs600 on her travel.

“It was a government job and I could not leave it,” she says. “I was street-smart. I managed to procure saris on credit and sold them in trains at a profit of Rs20 a piece. That made up for my losses.”

In 1994, she was posted as a regular teacher in Parkal mandal of Warangal, on a salary of Rs2,700 a month. By then, she had registered for master's in sociology.

The Parkal school had few students, as most parents in the area sent their children to a private school. Jyothi formed a parents' committee and encouraged them to send their children to the government school. The village sarpanch, Nalla Janardhan Reddy, donated two acres and sanctioned a new school building.

Giving back: Jyothi at an orphanage in Warangal, her hometown.

Giving back: Jyothi at an orphanage in Warangal, her hometown.

Now, the private school has been shut down. And there are 275 students and 16 teachers at the government school. Jyothi brought about this change in four years.

By then, she was promoted as a mandal girl child development officer. Her husband, too, moved to Warangal and took up a small-time job.

That's when a cousin, Jaya, came down from the US. Impressed with Jaya akka's style, Jyothi wondered aloud whether she, too, could go to the US. “You are aggressive and you can survive in the US, but I cannot help you,” was the reply.

The terse response was enough for Jyothi. In 1998, she applied for a passport and did a PG diploma in computer application.

In two years, she enrolled her daughters in a residential school and flew to San Francisco, with $1,000 in hand. There was no one to receive her. “I got the shock of my life. All people looked seven feet tall. I did not know how to use a pay phone. It took me half an hour to muster courage and call a known family,” she says. “They picked me up two hours later and said they would accommodate me for just a week.”

There were 40 families known to Jyothi, but none was willing to support her. She, however, was told she could find a job in New Jersey. She took a train to New Jersey, and found a job at a cassette shop, which paid her $5 per hour. The shop was 5km away from her paying-guest accommodation, so she would walk both ways to save on bus fare.

That’s when an acquaintance, who knew her as a teacher, asked her why she was doing a petty job when her field was IT. He told her about a job opening as an IT recruiter, at a monthly salary of $1,000. Jyothi extended her visa and shifted to South Carolina, where she would be trained on the job.

“I did not understand their English. I would put the phone down when they spoke to me,” she says. “I decided to improve my English, and started reading the Bible, which was free! Those notes are still with me.”

Today, while travelling across the world to deliver motivational speeches, Jyothi recalls those days. “Change is possible, but we have to try,” she says.

She mastered English and started recruiting people. Soon, Virginia-based software company ICSA offered her a job with a salary of $5,000, and free food and stay.

After completing a course in quality assurance testing, she went to Phoenix for an interview. She failed to make the cut, but fell in love with the place, as the weather reminded her of Warangal. Then, she made a quick trip home and consulted the priest at her favourite Shiva temple. He advised her to do trading.

“All I knew was software. On October 26, 2001, I started Key Software Solutions with three employees,” she says. Now, Jyothi has 163 employees and the company boasts a turnover of $15 million.

In the first year, there was no income. So Jyothi worked part-time as a babysitter. “It was good money [$16 per hour] and good food,” she says.

By 2003, her husband and daughters also migrated to the US. The daughters completed their engineering course and now work in the software sector. Both are married, too. “We still live together and, when I am not travelling, I cook for all and we eat together,” says Jyothi.

Jyothi has not forgotten the children of Warangal. She picks two Class 10 toppers from the district and gives them cash awards. She gifts other deserving students clothes, bags and material they would need for intermediate education. She also sponsors a home for special children.

“There are 3.6 crore orphans in India and I want to find a solution for them,” says Jyothi. She interacts with NGOs, government agencies and socio-political leaders to evolve better ways of empowering orphans. She has held discussions with a host of dignitaries, including former president A.P.J. Abdul Kalam (whom she calls her “mentor”), President Pranab Mukherjee, social activist Anna Hazare and Union HRD Minister Smriti Irani.

Her autobiography, Yet, I am Not Defeated, has been published in English, Telugu and Kannada. A biography of her's is titled `No Condition Is Permanent’.

The maxim of her life, Jyothi says, is simple: “If you have shakti, no shakti can stop you.”