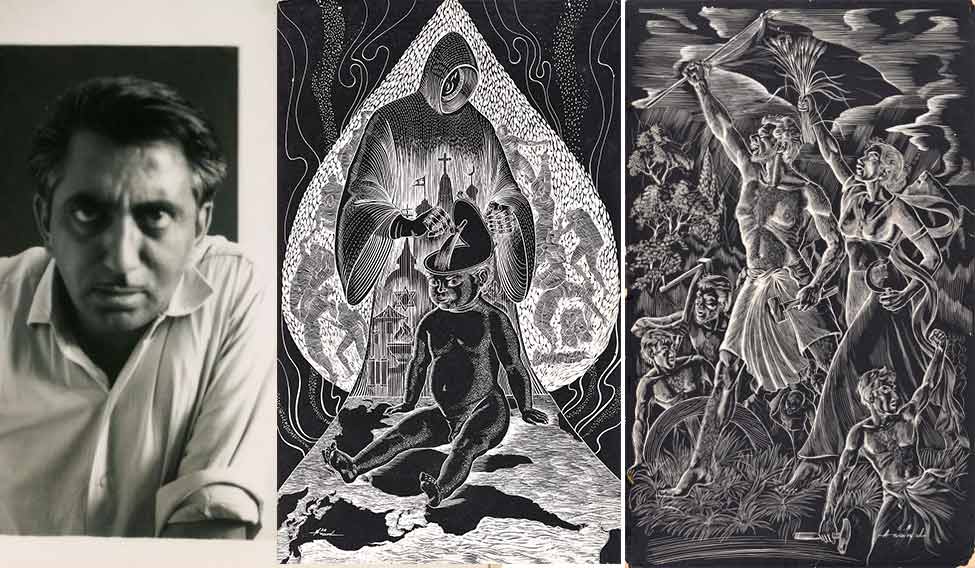

The image, etched on a scratchboard, was enthralling yet provocative. An eagle gouging out the eyes of a meditating Buddha, while a soldier took careful aim at the latter – a damning indictment of the 1960s US invasion of Vietnam.

Signed B.M.Anand. Attached to it was a note by the artist: The eagle of fascism drives its claws into the eye sockets of the compassionate Buddha. The blood drops falling from Buddha’s eyes arise up in a swirling conflagration. The spirit of Asia rebels against outrage on Buddha’s ideals of peace.Held as a collateral project of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2016 by B.M. Anand Foundation, the exhibition Art and Politics of Brij Mohan Anand did exactly what its name suggested—deconstruct one of the most important voices of the post- independence era, who died in relative obscurity.

Brij Mohan Anand (1928-1986) was born in Amritsar, nine years after his brother Madan Mohan was martyred in the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. Orphaned at the age of 14, he dropped out of school. He lived through tumultuous times in his teenage years and bore witness to the declaration of independence and the gory partition of India. Says curator Shruthi Isaac, “He never went to an art school. He was someone who learned by travelling, sketching the common man. His scratchboard images could be seen as a distillation of his initial sketches. It gives an insight into the artist's mind that he used this medium — tough, uncompromising and certainly unconventional.”

His scratchboard images from 1950s to mid 1970s are an unparalleled social and political commentary of the times, a narrative of strident dissent that eluded most of his contemporaries like M.F. Husain, S.H. Raza and F.N. Souza. Was it the adolescent helplessness which mutated into a fire of defiant rebelliousness and aversion to authority that characterised his works?

In 1955, he presented a painting in protest to Soviet premier Nikolai Bulganin and Communist Party first secretary Nikita Khruschev on their visit to New Delhi. The government reacted by revoking his passport. In 1972, he mailed New Year greeting cards to heads of state and embassies in India — a reproduction of his scratchboard work Stop Burning Asia. The painting, a protest against the US war in Vietnam, portrayed a Red Indian setting fire to Asia while death for the west lurked around the corner.

In other works like Who Does Modern Art Serve (1956), Anand critiques the art establishment for rampant commercialisation, profit motive and inaccessibility to the toiling classes. His Feudalism and Imperialism (1960) and Cultural Indoctrination (1961)decried imperialism, colonialism and Western intervention in Asia.

Says his biographer Aditi Anand: “There is no doubt that the events which marked his life played an important role in shaping his artistic sensibilities. From the bitter family legacy of Jallianwala Bagh massacre to the trauma of partition and the post-independence realpolitik of Congress and Communist party mandates, he recognised the self-deception, vanity of power and complicity of elites through which it was exercised.”

As author Jeet Thayil writes in his award winning book Narcopolis,“We honour the dead by repeating their names.” What was the treatment meted out to Anand after his death? Aditi says no information of Brij Mohan Anand was available in the public domain when she first ventured on the project to journal his life. Says Aditi, “There was this event in 1947, when he earned the displeasure of Sheikh Abdullah in Kashmir over displaying nude paintings at an exhibition. We tried to confirm the incident, but there was no information in the Kashmir archives. We finally managed to trace a 90-year-old Kashmiri artist who was present at the spot. Through the years, we managed to garner information by tracking people who had worked with him, known him and those who were present at the same place as him. We even called upon an erstwhile landlord of his. In 1974, Anand was about to present a painting to Indira Gandhi in protest against the Pokhran nuclear tests. We have not yet been able to track it down. We filed an RTI with the PMO, as any present that the prime minister or president recieves will have to be entered into a ledger and stored safely. But no luck.”

What made him descend into near-complete anonymity after his death? Did his paintings (like Who Does Modern Art Serve) irk the art establishment? Was he marginalised because he challenged the dominant narrative at the time?

“In the book, we hypothesise that it could be one of the reasons. Or it could also be that he did not want his art to be exhibited, in line with his utter abhorrence of commercialisation,” says Aditi.

What were his artistic influences? Researcher Dr Grant Pooke writes that, unlike his contemporaries who looked to the west for validation, Anand, “gazed to the Soviet and Occidental exemplars. The presence of an expatriate community, aside from Anand's own communist sympathies, may account for aspects of soviet socialist realism.”

Pooke says that his acquaintance with Russian artist Nicholas Roerich may have exposed Anand to the vernacular Russian art forms.

One interesting aspect about Anand's work: He never wanted anyone else to interpret his work and a printed note of his artistic vision always accompanied his sketches. Sample the literature that accompanies Feudalism and Imperialism: The ghost of feudalism and imperialism, wearing religious garb, opens out the skull of a child, takes out his brain and substitutes filth instead, creating clime for germination of servility and crime.