"Where do you live?"

"I belonged to Old Man Carver away in the woods. He made me."

"You've got funny eyes — and funny hair too."

"The old man made holes in my wooden head and then pushed blue beads into the holes" says the nodding man. "He made my hair out of bits of fur from his cat's back."

"Why have you run away?"

"Because it's so lonely with Old Man Carver ... and he's carving a lion now. I don't like lions ... I want to live with lots of people.”

This is how the first book in Enid Blyton’s Noddy series—Noddy Goes to Toyland—opens, recording a conversation between Big Ears and Noddy. I remember reading the stories of the little wooden boy with the nodding head whilst lying curled up on the bed in my third standard dormitory. Those were lonely days when I first joined boarding school. But Noddy let me escape to Toyland in his red and yellow car. I went on many adventures with him, Big Ears, Tessie Bear and Bumpy Dog.

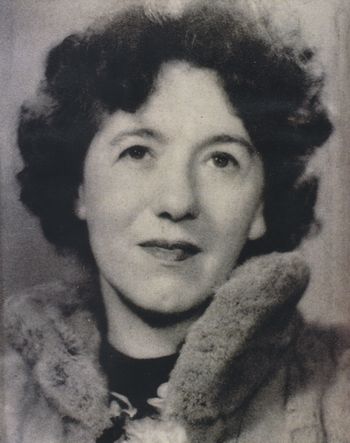

Of course, those days, Blyton was nothing but a loopy name scrolled on the covers of all my favourite books. I never gave a thought to what kind of woman she might be but if I had, I would probably have imagined a homely dame with her salt and pepper hair tied into a tight bun, typing away by the window of a charming English cottage overlooking a garden of periwinkles and lilies. If I had, I would have missed the mark by a wide margin. In reality, Blyton was a hard-headed woman with short hair and sharp features; there was nothing ‘homely’ about her or her life.

She was born in East Dulwich, South London, on August 11, 1897 and spent her childhood in Kent. Her life was latticed with many traumatic events, from the separation of her parents when she was young to her unhappy marriage to Hugh Alexander Pollock, who later became an alcoholic. Her first book, a collection of poems called Child Whispers, was published in 1922.

She was, reportedly, obsessed with her career and routinely cruel to her two daughters and Pollock. Still, her life was extraordinary in other ways. Lindsay Shapero, who wrote the screenplay of the 2009 BBC film Enid based on her life, said: “"It's true, she was certainly a terrible mother, but in other ways she was ahead of her time. She was an advocate of disabled children's rights, for example, and a working mother trying to balance her private and professional life." In the early 1960s, she was diagnosed with dementia. In 1967, her second husband, Kenneth Fraser Darrell Waters, died of renal failure, which was, for her, a heavy blow. Her health deteriorated and on November 28, 1968, she died in her sleep at the age of 71.

Blyton was a prolific writer who wrote between 6,000 and 10,000 words a day. She never planned her stories but sat at the typewriter and let her imagination steer the plot forward. “I shut my eyes for a few minutes, with my portable typewriter on my knee – and I make my mind a blank and wait – and then, as clearly as I would see real children, my characters stand before me in my mind’s eye… The first sentence comes straight into my mind, I don’t have to think of it – I don’t have to think of anything,” she said. Her writing was certainly aided by her photographic memory. “My imagination,” she wrote, “contains all the things I have ever seen or heard, things my conscious mind has long forgotten … I don’t think that I use anything I have not seen or experienced. I don’t think I could.”

Blyton never aspired to literary grandeur. Her style of writing was characterised by what one children’s writer called “aesthetic anaemia”. But her world of fairy folk, enchanted woods, faraway trees, lacrosse, ginger beer and exotic places like Kirrin Island and Smuggler’s Top held an infinite fascination for children. To this day, when I hear of buttered scones or gurgling brooks I think of the Blyton books of my childhood. But her influence was not just a cosmetic one. Perhaps I’ll never be able to measure how much of my psyche was impacted by her stories. She taught me to imagine my way into the adult I became.