Ammu, Velutha, Estha and Rahel—characters immortalised by Arundhati Roy in her masterpiece novel God of Small Things. Roy also introduced to the world another star character—Kerala's river Meenachil— that anchored the story set in the village of Aymanam. Beyond books, Roy's Meenachil which once served as the lifeline of many people had been facing a slow death over the years—its tributaries choked by pollution, sand mining and encroachments. Thanks to a bunch of river warriors, the river is now getting a fresh lease of life. A unique people's movement is on a mission to rejuvenate the river—cleaning and relinking it with its tributaries Meenanthara and Kodoor in Kerala's Kottayam district.

What started as a small group's voluntary initiative has now grown into a multi-faceted green project which will inspire many more such movements across the country. As a well-deserved recognition, the project won this year's Bhagirath Prayaas Samman, an award constituted to recognise initiatives for river conservation.

Birth of a movement

In June, Green Fraternity, an NGO, made an attempt to clean and rejuvenate Meenanthara river —a 5km long tributary of the Meenachil river which was almost dead due to pollution. Meenanthara river, which was once the trade route from Kottayam town to eastern Kerala, had also served as an ideal breeding ground for more than 70 varieties of fishes. Now, aquatic diversity was drastically affected and thousands of acres of paddy fields in the basin turned barren. Grease floated on the water, and an epidemic loomed over those who lived near the river. Many rivulets connecting Meenachil to Meenanthara river had turned dry as illegal sand mining had altered the route of of the Meenachil river.

New lifeline: Excavators and JCBs were used for the rejuvenation of capped rivulets and streams | River restoration campaign

New lifeline: Excavators and JCBs were used for the rejuvenation of capped rivulets and streams | River restoration campaign

Despite multiple complaints to authorities, the only action they took was to put a sign board warning people of contracting rat fever lest they step into the water, said Dr Jacob George, president of Green Fraternity. Disappointed with this response, the NGO decided to take up the task on their own. “Our green army of six volunteer worked for two continues weeks to clean the river,” said George. The lion-share of the expense for this effort was met from George's pension. As the clean-up progressed, George and his team realised they had a herculean task at hand—all their efforts would turn futile if the pollution inflow from the Meenachil river was not addressed. Such a massive project could not be funded from their kitty, and they approached advocate K. Anilkumar, an environmentalist and a local politician. From there, the project transformed into a public-funded mass movement, and Anilkumar helped connect the efforts of people with the different government departments. “On August 16, six of us made a journey in a small boat to study the issues in detail,” said Anilkumar. “Based on that route identified, a puzhanadattham (river trail) of around 300 people was organised to raise awareness among the public. We inspected the places where the river was encroached upon and narrowed down.”

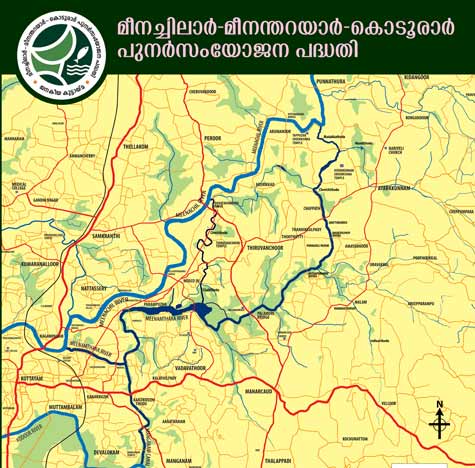

George and team are not the first to have taken note of Meenachil's plight. In fact, the river's rejuvenation efforts date back to over a decade. When the current project was at the crossroads, looking for a new direction and a solution, Kottayam Nattukoottam, a centre for cultural and heritage centre's studies about the original river routes came to the rescue. Bringing back river basin agriculture and sustaining continuous water flow in the river was the only way forward. “The clean up and restoration of the old water route by re-linking the Meenachil river with its tributaries—Meenanthara and Kodoor rivers, and rejuvenating the dead rivulets would bring back agriculture,” said Rajiv Pallikonam, secretary of Kottayam Nattukoottam. Pallikonam prepared a detailed map of the full river restoration-relinking plan using Google earth images. The relinking project was presented at a seminar held in Kottayam on August 28, where Thomas Isaac, Kerala finance minister, was present. The project proposed the possibility that if the relinking is happening, then, lot of barren paddy fields could be restored with agriculture, the fish breeding in the Meenanthara river will be rejuvenated, flooding of the Meenachil during rainy season will be checked, drinking water facilities will be facilitated and overall ecological balance of the region will be restored. Also, the future possibility of heritage inland water route tourism was also presented. All these came as add-ons with solving the pollution problem.

The river relinking map

The river relinking map

The restoration of old water routes was not easy as it was on paper. The overall effort required to clean up and revive more than 40km of canals, streams and rivulets. In many places, the river was encroached upon. The cleaning of Amayannoor Arraattukadavu (idol immersion ghat) was decided as the inaugural activity. But, September 10 saw a more aggressive start by a gathering of more than 200 volunteers—a rivulet was cut through an encroached and landfilled plot in Kottathilparambil. The idea was loud and clear—the collective was daring to challenge any blocks in achieving the goal. The group's activities were met with suspicion from the local people at first. But soon as water started flowing through the once dead rivulets, more and more people started joining the activities and donated money for the cause. Various nature clubs, environmentalists, professionals, resident associations and members of different political parties joined the effort. In certain places, residents even donated the land for widening the flow of water bodies.

“The state government is supporting us from the start itself,” said Rajiv. The irrigation department has allocated a Rs 2 lakh budget for preparation of a detailed project report which have an estimate of Rs 2.5 crore. The department is also seeking the possibilities of lift irrigation in different areas. The agricultural department has sanctioned a fund of Rs 1.5 crore for resuming agriculture in the river basin. The revenue department came up with a plan to check the boundaries of public rivulets and streams. Also, in order to protect the rivulets and streams of the three rivers, a comprehensive project under the three-tier panchayat system utilising the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act programme was launched on November 1. Another project to cover and protect the entire stretch of Meenachil river with coir garment has been approved and Rs 9.82 crore allocated, which will be first of its kind project in Kerala.

Besides reviving the river, the most significant achievement is that agriculture is making a comeback to more than 1,100 acres of fallow paddy fields in the river basin. Inaugurating the re-cultivation of paddy field, Agriculture minister V.S. SunilKumar said: “This project is setting a great model to the entire country—a unique model of people-government cooperation for the protection of nature. And rightly, the state government will take this project as a model project for the Haritha Kerala Mission.”