Growing up, there were no libraries in Malayalam writer Perumbadavam Sreedharan’s village. But he was a voracious reader, relentless in his pursuit of books. On an occasion, he came across a book that fascinated him—Crime and Punishment, written by a Russian author named Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821-1881). Could he borrow it? The owner was unwilling. “Why?” he was asked. “What would you know about a book like this? You won’t understand it.”

Sreedharan was crestfallen. As he started to leave, the man agreed to part with his book—on one condition. “If you can return the book by tomorrow evening, you can have it,” he said. Back home, Sreedharan burnt the midnight oil. By the time the first rays of the sun touched the ground, he had fallen head-over-heels in love with a writer from a distant land, whom he had never heard of in his life. “I don’t even remember how he looked,” says Sreedharan, in conversation with THE WEEK. “But I can never forget him.”

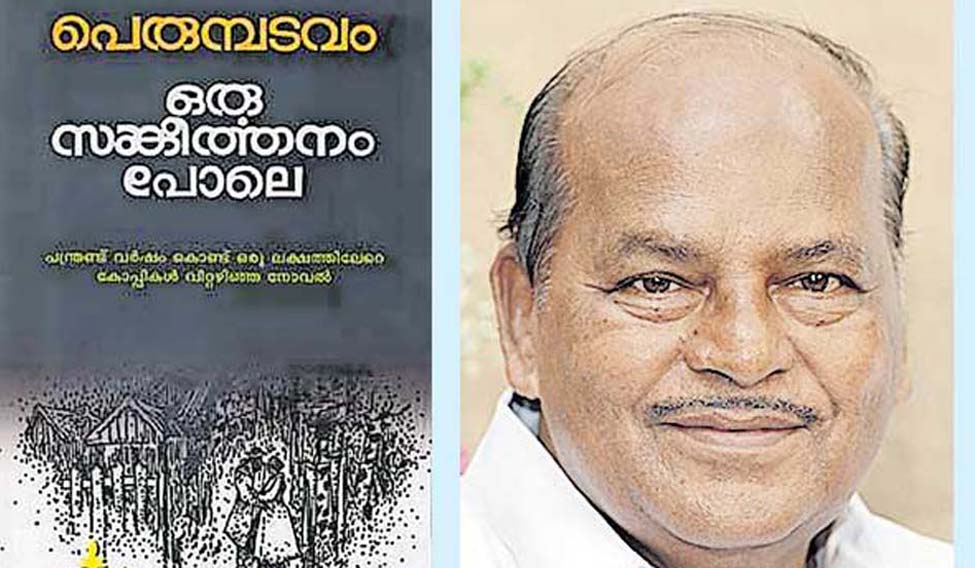

Several decades later, Sreedharan would go on to pen a book about Dostoevsky, called Oru Sangeerthanam Pole, which was released in 1993 and went on to become one of the most popular books ever written in Malayalam. In 1996, Sreedharan was awarded the prestigious Vayalar Award for the book.

In a way, the tribute was deliciously contrapuntal. Realism was the soul of Dostoevsky’s works. Take the case of his iconic Crime and Punishment: every bridge, road and path traversed by protagonist/antagonist ‘Rodya’ Raskolnikov—the handsome, tortured youngster who oscillated between supreme intellectual self-detachment (obsessed with his own ‘extraordinary’ self) and the pits of obsequiousness—had a mirror image in the underbellies of St Petersburg. It took 730 steps, wrote Dostoevsky, for Raskolnikov to reach the doorsteps of the old pawnbroker from his own dilapidated lodgings. “Even today, you can walk the route he followed and count the number of steps,” writes Professor Virginia P. Morris in her extensive, eponymous analysis of Crime and Punishment. For his part, Sreedharan had never been to Russia. But, sitting half a world away, he reanimated the writer and the promised land of St Petersburg with an intimacy that betrayed otherwise.

On December 2, Kerala Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan launched the 100th edition of the book—one of the final surviving relics of the overarching Soviet influence in the state in the 1960s and 70s that shaped the perspectives and sensibilities of generations of youngsters. It was an era of the Soviet soft power—the hedge against hostile Western overtures—in all its glory. Packets and stacks of heavily subsidised Soviet literature showered down from the heavens. For the younger ones, there were the glossy, colourful magazines—ones like Misha, Soviet Land, Sputnik—offering a peek into a brave new world that seemed just out of reach. Then there were the siren songs of the Russian authors—Tolstoy, Chekhov, Pushkin among many others—that became household names, making their way into everything from your favourite salon to your friendly, neighbourhood vegetable vendor. Sreedharan says there was a profound influence of Russian writers in the Kerala of the ‘60s and ‘70s. “There were those like Edappally Karunakaran Menon who translated the works of Soviet authors,” he says. “The credit of popularising Soviet literature in India largely goes to Progress Publishers [a Moscow-based Soviet publisher founded in 1931].”

Cover page of Perumbadavam Sreedharan's 'Oru Sankeerthanam Pole' | via Manoramaonline

Cover page of Perumbadavam Sreedharan's 'Oru Sankeerthanam Pole' | via Manoramaonline

But, for Kerala, the tallest among all was Maxim Gorky—in every way, a regalia of ‘Soviet invasion’ of the tiny tropical state. His works—a subtle blend of romanticism and searing critique of the status quo that inflamed the minds of the youth—became a mainstay of India's freedom movement. Mahatma Gandhi, who was a great admirer of authors like Tolstoy and Gorky, once wrote about the latter: "There is no other writer in Europe that is as great a champion of people's rights".

In Kerala, the author's works were ubiquitous, and his influence—indelible. Says K.R. Meera, the award winning author of Aarachar (Hangwoman), “In the fifth grade, when I won a prize in an extempore competition, one of my mother’s colleagues gifted me a copy of Amma [the Malayalam translation of Mother, the story of a proletarian revolution set in a factory in Russia]. The book changed my perspective and outlook in life. It brought me out of my upper middle class cocoon and showed me that there was a whole wide world out there. As someone born in the 70s, I grew up with those magazines and books—the Soviet Union’s most significant contributions to Kerala,” she says.

According to CPI(M) MP M.B. Rajesh, the Soviet literature played a huge role in moulding the Malayali’s cultural and predominantly leftist mindset. It also coincided with a period of renaissance in the state of Kerala, marked by a rise in literacy and rapid spread of education. "When I was young, I remember that my family had subscribed to Soviet Land. A lot of children in Kerala are named Natasha, after a character in Gorky’s Mother. Russian names became very common in the state, in part due to the aftermath of October Revolution. For me, personally, it was Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer’s travelogue of his journey through Soviet Union that planted the desire to some day visit Moscow myself.”

Then there was the near-universal relatability that characterised most Soviet translations. As many books have chronicled, Gorky’s hard life experiences influenced both authors like Kesavadev—who passed through similar tribulations—and the progressive writers from more privileged backgrounds like Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai. And it is exactly this factor that prompted—nay, compelled—Perumbadavam Sreedharan to recreate his tortured muse, based on what little information he had. To capture the writer’s stormy life, and his complex temperament, was no easy task. Dostoevsky was arrested in 1849 (Tsarist Russia), sentenced to Siberian prison camp, escaped the noose by the skin of his neck, and led a life that was ravaged by ill-health, alchohol and gambling addiction.

Soviet propaganda poster | Wikimedia Commons

Soviet propaganda poster | Wikimedia Commons

Just as difficult to interpret was his relationship with his stenographer Anna Snitkina, which becomes the premise of Perumbadavam’s book. As the story goes, while Dostoevsky was writing a book called The Gambler, he made a deal with his publisher. He would have to hand over the rights to all his works to the publisher unless he could finish the book by a specific date. As the deadline was fast approaching, he hired a stenographer called Anna to help him. Anna was only 20 or so when he was 45 but she understood him—his volatile temperament, his insouciant spirit and his despondent moods—better than anyone else. When the publisher tried to change the terms of the deal to appropriate the writer’s works, it was she who took the manuscript to a police inspector to try to get his help. The inspector asked Anna who she was to come to the aid of the writer. Without thinking, she replied: “I’m his wife.” That’s when she realised that she was in love with the writer.

“That story moved me more than anything else. We [me and Dostoevsky] have both experienced poverty,” says Perumbadavam. “I was born poor and he was led to it through his experiences. Writing the book was more a revelation than a conscious decision. It was almost like falling into a pit. There was an inevitability to it.”

“Perumbadavam’s book can be read as a Russian book that originated from that country,” says Meera. “It was a major example of how cultures intermingled at that time.”

With the passing years, the Kerala readers have established a sense of ownership over their favourite writers. As the adage in the state goes: “Dostoevsky and Marquez [Gabriel Garcia] are one of us. They are Malayaalis.”