Recently, former US president Barack Obama made a very important statement. It is something we women have known for ages, something we have been urging men and the rest of the society to consider more seriously; a message we want all mothers to take to heart, especially while raising little girls.

Obama said, “Elect more female candidates”. Feminists have been urging for this shift for years now—choose more women CEOs, team leaders, managers, and so on. The message is clear. When women are in a position of power, the dynamics change. The atmosphere for women in the work place becomes more conducive. A female boss encourages women to be more vocal about problems in a work place as opposed to when men are in charge, which is often the case. According to research, cases of sexual harassment are less in organisations where there were more women in managerial positions.

Also, strangely, there seems to be a direct relationship when it comes to power and sex. Power in a workplace, and the tendency to harass a female co-worker, is directly proportional to each other. It is you on the high chair. You, the male head of the company, can hire her, fire her, offer her a raise, demote her—then how could she speak up against you, right?

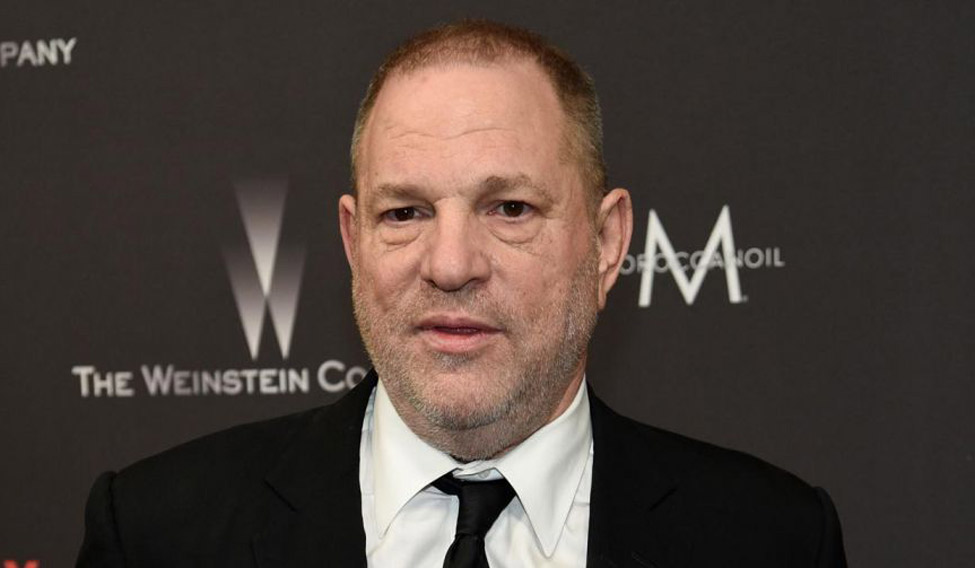

In October this year, about 80 women came out accusing big-time Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein of sexual assault. This gave way to the #MeToo campaign, started by actor Alyssa Milano who wanted to encourage women to come out with their stories, no matter when it happened. Not only did the movement go viral, it gave hordes of women and men courage to speak up about their experiences, bringing to light the gravity of the problem. It gave us a peek into the ugly side of society, where, in so many such cases, the victim was usually blamed. Consider the usual refrains: "She was wearing provocative clothes", "I thought she came on to me", "She was out alone, late at night", "What was she doing alone at a bar, unescorted?". While victim-shaming is a topic for another day, the spotlight, now, should be on men who think they can get away with it.

Post the Weinstein episode, many more men in positions of power were accused of sexual misconduct. Actors like Kevin Spacey and Charlie Sheen, or the many Congressmen and leaders like Al Franken, Trent Franks, John Conyers Jr, Blake Farenthold, Ruben Kihuen, and US President Trump himself came under the hammer! Like television host, comedian and actor Chelsea Handler rightly said at the Bill Maher show last month, the problem was that people did not mind electing a predator, but hesitated in electing someone who has been with one (a predator). While campaigning, Trump conveniently attacked Hillary Clinton for being married to one of the greatest women abusers in the history of politics. On the flip side, Trump himself had a slew of sexual misconduct allegations against him. Trump has been accused by no less than 16 women of sexual misconduct. The situation again puts women in a corner, not the men.

Dana Nessel, the Democratic candidate for Michigan’s attorney general, released a provocative advertisement asking which candidate they trusted most not to show you their private parts in a professional setting? The answer—a candidate that doesn’t have one—implied that they should vote for her. Nessel does make an important point here. Power plays its part in letting men think they can “get away” with mistreating a female colleague.

A few actresses have confided that they have felt Weinstein took them off projects, or asked others to do so, after they refused his sexual advances. Another perpetrator brought to light late November—Matt Lauer, an American television journalist—would use a button under his desk to lock women in his office. Also, his office was so far placed that no one would walk in on him misbehaving with female subordinates. The women who came out to speak against him, chose to speak in anonymity, fearing repercussions for being vocal.

In a research titled Sexual Aggression When Power Is New: Effects of Acute High Power on Chronically Low-Power Individuals, psychologists found that more men and women in power felt that their subordinates were sexually interested in them. It also revealed that men who were feeling powerless over an extended period, but then experience new found authority, are the most likely to sexually harass, compared to other men. Yet, another similar research revealed that people in powerful groups developed empathy deficits that make them less able to read others’ emotions or take their perspectives into consideration. Also, the men in this case tend to erroneously believe that women are more attracted to them than they actually are and they tend to sexualise their work that makes way for behaviour like inappropriate leering and unsolicited touching.

Again, this is not to say that all men in positions of power have corrupt minds when it comes to behaviour towards the opposite sex. But, power does put a blindspot on emotional qualities like empathy that prevents them from making the wrong advances. A cousin's friend recalled the time she was an intern at a reputable star hotel. She was helping out a floor manager at the business centre where the clients were to be served breakfast. She was carrying a jug of water back to the kitchen area, when she stumbled and water drenched her white shirt, rendering it transparent. The floor manager blocked her and tried to brush off the water while all she could do was somehow get away.

“I had no choice but to put my head down and get on with the breakfast service,” she recalls. A colleague of mine confided about how a super boss at her former organisation came on to her verbally by making inappropriate comments like “no one can see through my cabin as the walls are opaque” and “there's even a couch now in my cabin”. It culminated in him openly asking her out, an invitation which she refused. Though he did not pursue her any further, it made her feel uncomfortable about her self-image and work ethic for the rest of the time she worked there.

Coming back to what Obama said, hiring more women at the top—at workplaces and at places of governance—will surely make things better. Things will also change for the better if men take accountability of their actions and women support other women who are contesting for places of power.