I was waiting outside the gates of the Apollo Hospital in Chennai talking to my sources and media friends on the night of December 5 when the hospital issued a statement announcing the demise of chief minister Jayalalithaa Jayaram. Even though I had been expecting the announcement, when I actually received it, it shook me for a second from head to foot. My blood pressure shot up, and I felt sad for her as a woman. I had seen her at close quarters early in my career and I had experienced her charm as well as her ruthlessness.

I had started my career in 1999 as a cub reporter at a regional TV channel that was on air for just three months. One day I accompanied a senior reporter to Kundrathur on the outskirts of Chennai, where Jayalalithaa’s auditor K. Rajashekaran lay in a bed in a small room. His hands and an eye were swathed in bandages and there were bruises and swellings all over his body. He had allegedly been beaten with footwear and a stick by two woman and a man, who had forcibly made him sign on stamp papers. I was shocked, but it made me read up on the AIADMK and its leaders.

When the TV channel closed down, I went back to Coimbatore to join my father’s small business. But not long afterwards, I was back in journalism: I had joined another channel in Chennai. I was too raw to be assigned political reporting, but I made it a point to accompany my seniors whenever Jayalalithaa appeared in the special court, opposite the Madras port then, in Parrys Corner. Every time she arrived, high drama would unfold. Women ran alongside her car, hitching their saris above their knees and screaming slogans in praise of her. The words puratchi thalaivi (revolutionary leader) rent the air. I remember her alighting from the car on February 2, 2000, clad in a light green sari. She was accompanied by her close aide Sasikala, who was in a dark green sari. We were waiting with our beta cameras and long microphones in our hand, and were pushed back into a corner by the long ropes held by her hefty private security men.

And after an hour, she came out with a grim face, with anger in her eyes, and she refused to comment. Special judge V. Radhakrishnan had convicted her in the Pleasant Stay hotel case. Her party men were milling around. The moment she got back into the car, we all started running but I did not know why. I ran more than a kilometre from the special court till the state secretariat on Beach Road. There I stopped and saw my senior reporter, and learnt that AIADMK cadres had gone berserk on hearing of her conviction in the case. Violence broke out across the state, and three agriculture college girls were burnt alive in a bus, about which I read the next day.

Yet, in February 2001, I joined Jayalalithaa’s TV channel, Jaya TV. The assembly elections were months away, and at the job interview the only question that was put to me was about the prospects of the two Dravidian parties. Without hesitation I said, “AIADMK will come back to power with a massive mandate, and the Congress and G.K. Moopanar’s Tamil Maanila Congress and Dr S. Ramadoss’s Pattali Makkal Katchi will be with her.” I got the job and I cut my teeth as a political reporter in the election campaign in 2001. And I was reporting for Jayalalithaa and about Jayalalithaa. I had to report what she spoke and how the party men received her and hailed her, and how cheering crowds waited for her for hours. But I liked it.

On May 14, she won absolute majority, with 147 MLAs. This was the first time I went inside her Poes Garden residence—even though the Jaya TV office was in an adjacent building, I had never had the opportunity to be within her swanky residence. As a reporter, I had always stood with the rest of the media outside the gates. And on May 14, she was on the portico, accepting greetings from her party men and her well-wishers. I saw VVIPs with bouquets and gifts waiting to meet her in a line that was at least half a kilometre long. Some people fell flat at her feet. But, somehow this victory of hers inspired me as a young woman in her early 20s. I told one of my colleagues, “Wow! She is superb. See men falling at her feet.” I had turned her fan.

Late in the evening, she set out in a convoy to the party office for a meeting of the MLAs and then went to the Raj Bhavan to meet the Governor and hand over the letter of support from her MLAs. I was in the convoy, in a car in front of the chief minister’s posh car. I felt joyous. The cheering crowd made me feel what it is being a chief minister. From the Raj Bhavan she went straight to the state secretariat and signed a file in green ink. And then, the press conference. My first experience covering a chief minister’s press conference. She said, “You all wrote me off. I have come back.” I liked it.

And then, almost every day I was in her convoy, reporting all her events, public meetings and appointments. A month after she was sworn in as chief minister, the editorial staff from Jaya TV had a special appointment with her. She had the courtesy to thank even people like me for our contribution, in the way of TV coverage, that helped her come back to power. She spoke at length with the news anchors and the editor. I was standing right behind her and just listening. She sounded very soft, all her words were measured. She was all smiles. Clad in a light lavender sari draped around the shoulders, she looked beautiful even though she did not wear any ornaments. After 20 minutes it was time to pose for pictures. I chose to stay away. But she called out to me, “Pappa,” meaning baby, “come stand next to me.” I was so taken in. From next day all my colleagues at Jaya TV started making fun calling me “Pappa”.

In September 2001, she had to step down as chief minister on being convicted in the TANSI land deal case. I witnessed the tense moments in front of the Poes Garden gates. Names of several MLAs like Uppiliyapuram Saroja, who was one of the ministers, did the rounds as likely chief ministers. Jayalalithaa’s choice was O. Panneerselvam. She then went back to court in appeal in the case. On December 4, 2001, when the High Court acquitted her, I ate not two or three, but twenty laddus, offered by the party men. Her convoy was out there in front of the Jaya TV gates. I got into the convoy to travel with her. As she went to the Vadivudaiamman temple in Thiruvottiyur, near Chennai, I was there to take an exclusive sound bite. She was happy and so was I. By this time I had become a hardcore Jayalalithaa loyalist.

I covered her by-election campaign in Andipatti for more than 15 days. Thanga Thamizhselvan, the MLA from Andipatti, had resigned for her to contest to the assembly and come back as chief minister. On lean days when she took off and there was no campaign meeting scheduled, I, with my team of camera persons, watched movies sitting on the mud floor in old theatres in Kambam near Andipatti.

She came back to power and her first day in office was a Sunday. The scribes were waiting near the portico in the secretariat. I was also there. NDTV’s Jennifer Arul, after congratulating Jayalalithaa on her victory, asked the first question: “How would you describe your comeback and what do you feel?” When Jayalalithaa answered her, I asked her to repeat it in Tamil. She said, “Come forward, put your question, I will reply.”

In December 2003, the AIADMK was chalking out strategies for the Lok Sabha polls due in 2004. As our convoy reached the Vijay Sesh Mahal in Vadapalani, now the popular Green Park hotel, I alighted from the slowly moving Jaya TV vehicle, the microphone in hand. Her car stopped. She was all smiles, and beside her was Sasikala. She saw me running and she asked me, “What is your name?” As I said “Lakshmi” she smiled as if in appreciation of my doing my job. I felt like I was on cloud nine.

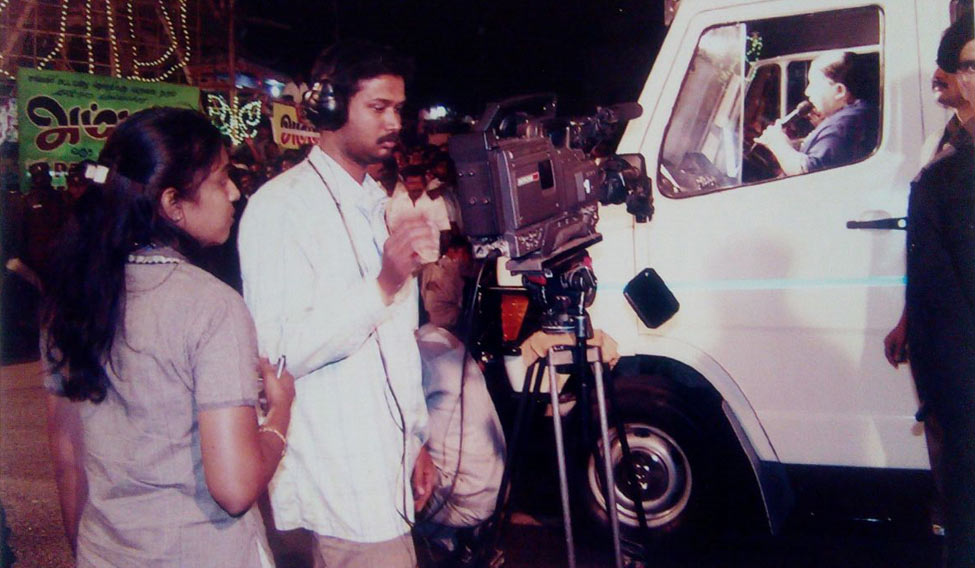

Lakshmi (left) during a shoot with the Jaya TV team in Salem ahead of the 2004 Lok Sabha elections

Lakshmi (left) during a shoot with the Jaya TV team in Salem ahead of the 2004 Lok Sabha elections

On Sunday, December 26, 2004, when the tsunami struck the coast of Tamil Nadu, she was out at work at 8am. I, too, was there, holding the microphone before her car, calling her “Ma’am. Ma’am” . She stopped the car, and said, “It is a devastation. The government is for the people.” I had to give the video cassette to my colleagues in the office, and then go with her in the convoy. It was a full-fledged but brief interview. My second one with her. As she paused, I shouted to my camera person, “Take out the cassette.” She looked at me, gave a minute for me to hand over the cassette to my colleague waiting near the office gate. Then I went on to report about her meeting the affected people in Nagapattinam, Cuddalore and other places.

In January 2005, I sought an appointment with her so that I could give her my wedding invitation and seek her blessings. I had sent a letter through one of her secretaries for the appointment. Just as I was waiting to be called, came the bad news. On January 11, I was called by my top boss in Jaya TV and told that Jayalalithaa had asked me to go. I asked why. A detailed mobile bill was on his table, which showed that I was talking to my friends in the rival Sun TV now and then. I still remember the mobile number: 984007044. I left my Jaya TV ID card, accreditation card and sim card on his table and walked out. I tried meeting Jayalalithaa as I wanted to know the exact reason for sacking me. It took me months to digest it. By then I was married and my husband’s support helped me deal with the misery. I found another job as a journalist.

In May 2006, Jayalalithaa lost badly to the DMK in the assembly elections. Her party won just 61 seats and she lost power. A press conference was called at her party headquarters in the evening. I was there in the front row. When I asked a question, she deliberately ignored it. Her face was red, her eyes were smouldering in anger. The press conference was quickly over. She was in a dark green colour sari and I was in a green salwar. As she got up from the chair and walked out after the presser, she looked at me and said, “Betrayer. Are you back? Mahalingam, don’t let this girl inside here after.” She then said something menacing that I don’t want to report. Before I could reply, she walked off. One of the senior journalists who had been covering the AIADMK for decades consoled me, told me not to dispute with her and that things would change.

Yes, things changed. In 2011, she was back in power. After the first press conference at the state secretariat, I went in to greet her, she remembered me. “Lakshmi,” she said. She was all smiles as she greeted me. She had changed and forgotten everything. But, I did not and I may not be able to. After that in these 10 years I have covered many of her events and press conferences. But not with the same admiration or attachment I had felt for her during my Jaya TV days. Even when she was in hospital, I felt a sense of detachment I as reported on her health. I felt no emotions, except for that single second after I got the hospital press release that announced her death. Yes, she is dead. She will not come back. But, her style and smartness and her anger against me definitely helped me evolve as a journalist in these 17 years.