One does a whole painting for one peach and people think just the opposite—that particular peach is but a detail.

Pablo Picasso

The closer I looked, the more it unravelled itself, layer by layer, line by line. The obvious appeared at first glance, the not-so-obvious waited to be discovered by the watchful eye.

The illustration had caught my wandering eye the moment I stepped into artist Bara Bhaskaran's 'Amazing Museum' at Aspinwall House which is part of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2016.One of his drawings—titled Amazing Museum IV—encapsulated everything that touched his soul in Bihar while covering the state assembly elections in 2015, along with noted Malayalam author N.S. Madhavan, for THE WEEK magazine where Bhaskaran is illustrator.

He remembers being overawed by the sight he saw when he got down from his car on the Mahatma Gandhi Setu—one of the longest river bridges in Asia—connecting Patna and Hajipur. “The river Ganga stretched out in front of me like the sea. I asked myself, 'Is it possible for me to reproduce the splendour of the majestic river on a piece of 120cmX240cm paper?',” he reminisces. But he did, in his own inimitable way.

And it did not stop at the Ganga. The fertile floodplains followed. “The flooded river might cause the people in the region much distress, but I realised it is, actually, a boon in disguise because of the mineral-rich silt it leaves behind,” says Bhaskaran. The thatched huts, dusty lanes, lazing cows, dung cakes, and chulhas transport you to the village life beyond the fertile fields. While the kushti match reminds you of the traditional sport and the pehelwans, the sight of a man being whipped gives you a rude insight into the exploitation and abuse of the lower classes. Buddhism, too, makes its presence felt in the Amazing Museum IV, in the form of inscriptions. Human figures—the sons and daughters of the soil—peek out from thousands of ink strokes, all of which took him half a year to complete. “Drawing a landscape is not merely reproducing what you see on to the canvas. It involves understanding the history of the land, its present and its soul,” he says.

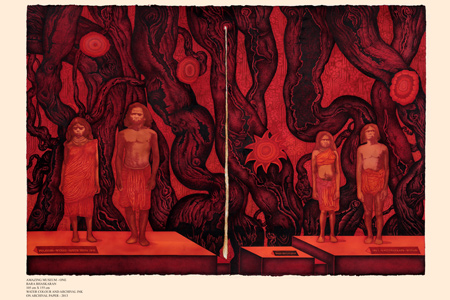

Amazing Museum One

Amazing Museum One

Be it Bihar or Kasaragod in Kerala, where Bhaskaran was born, or Wayanad, where he spent years working on a biography of tribal leader C.K. Janu, it is the land, the marginalised sections of society and their everyday struggles that have always attracted him. Perhaps, that explains his 'Amazing Museum One', which shows two tribal couples being 'exhibited', or, should we say, up for sale. It might well be an ode to the slave market of Wayanad in the olden days.

The past always had a haunting presence in Bhaskaran's works. That, coupled with his keen sense of observation, brings to life people, places and objects that have long been forgotten and would not be found in history books or tourism brochures. The collection of some of his illustrations, for instance, titled Amazing Museum V, is a testament to his eye for the seemingly unimportant beings around us. The visual travelogue, which spans 12 years, has been published as a column titled Ente Keralam Rekhakal (My Kerala Chronicles) in the Malayalam literary magazine Bhashaposhini since 2000. There are also illustrations from Adukkala (Kitchen), a series of illustrated writings on kitchens and cuisine of Kerala.

It is Bhaskaran's assemblage of stories from different places that has always impressed Bose Krishnamachari, president of Kochi Biennale Foundation. “He [Bhaskaran] brings multiple thoughts, multiple stories, in the form of a narration. What I like is the way he depicts history through people and places, using the elements embedded in these locations. “For instance, his illustrated writings on food... how it is cultivated, how it originated, its taste... beautifully convey the experience to the reader,” says Krishnamachari, whose association with Bhaskaran goes back many years. Bhaskaran was part of 'Everything'—a group show by 12 Indian artists—held at Willem Baars Projects, Amsterdam, in 2008, which was curated by Krishnamachari.

“There is an overwhelming presence of children, women and the poor in Bara’s visual history,” wrote K.T. Rammohan, dean, School of Social Sciences, MG University. I remembered his words, as elderly women, shy teenagers and weary prostitutes looked down on me from the frames mounted on the walls. Among them, I noticed an illustration of a printing press. “That's painter Raja Ravi Varma's press, which is in a Manipal museum now. Its historical value is immense—it 'humanised' the Hindu gods; it brought the gods out from the dark confines of the sanctum sanctorum on to the walls of houses,” explains Bhaskaran.

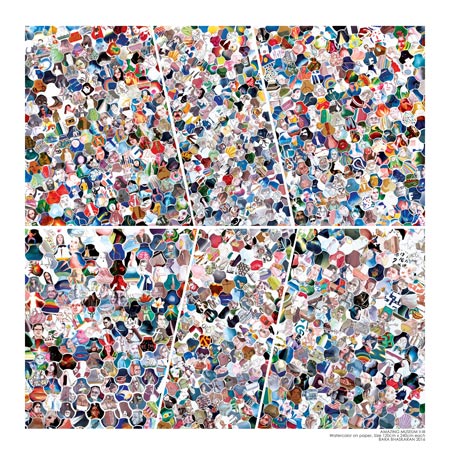

Amazing Museum II-III

Amazing Museum II-III

From Raja Ravi Varma's press, we moved on to a printing press closer home. The innermost room housed a mosaic of illustrations—titled Amazing Museum II-III—Bhaskaran did for columns that appeared in THE WEEK magazine. There was Manmohan Singh smiling meekly, Smriti Irani looking thoughtful, Khushwant Singh looking ancient (was he ever young?), a drum here, a noose there, a steaming cup of tea.... “The topics of the columns ranged from politics to art, literature, music, sports, society and what not. In print, these illustrations were complemented by text. So, here I have tried to emphasise that art can manifest itself in many forms, irrespective of the medium where it appears,” he says.

These “little tiles” appealed to Sudarshan Shetty—curator of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2016—the most, among Bhaskaran's works at the biennale. “It is like jigsaw puzzle of the complexities he sees around him... a larger social commentary on things, be it political, or a larger picture of the world view that he presents to us,” says Shetty.

“Why the interlocked format?” I asked Bhaskaran. “I talk about the soil, about roots... interlocking bricks hide the soil and bury the roots. It was not so in earlier times. The format has a meaning here...,” Bhaskaran replies with a Cheshire cat-like grin, leaving the sentence hanging mid-air.

As I looked around me, Picasso whispered into my ears, “Painting is a blind man’s profession. He paints not what he sees, but what he feels, what he tells himself about what he has seen.” Standing in that whitewashed, strategically-lit room, I watched in awe what the artist's eye had murmured to his soul.