Prime Minister Narendra Modi has once again rekindled the Jawaharlal Nehru vs Sardar Patel debate when he squarely blamed the first prime minister for the entire Kashmir issue. “The whole of Kashmir would have been with India if Patel was allowed to become the first prime minister,” said Modi in his recent speech in Lok Sabha.

It was not the first time that Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party questioned Nehru's political legacy. During his campaign for the Parliament elections in 2014, Modi had claimed that India would have been served better if Patel (instead of Nehru) was the prime minister after independence.

Modi's latest dig at Nehru has, as expected, drew sharp reactions from the grand old party which rebuked the prime minister's “total ignorance” on India's partition. Quoting history texts and documents, they were quick to remind the prime minister that Patel was the first and strongest among the Congress leaders to support the British plan to divide India.

However, how much does the Congress argument that both the leaders worked together as “comrades” hold water? Historians have attested to the political rivalry that existed between the two statesmen, especially during the immediate months after the independence.

Being the tallest leaders of the Congress party, Nehru and Patel were the only contenders to the post of Congress president in 1946, a stature which would naturally pave way for the prime ministership after independence. As the provincial committees of the party remained divided in their choice, the final decision lay with Gandhi, who preferred Nehru over Patel as the party chief.

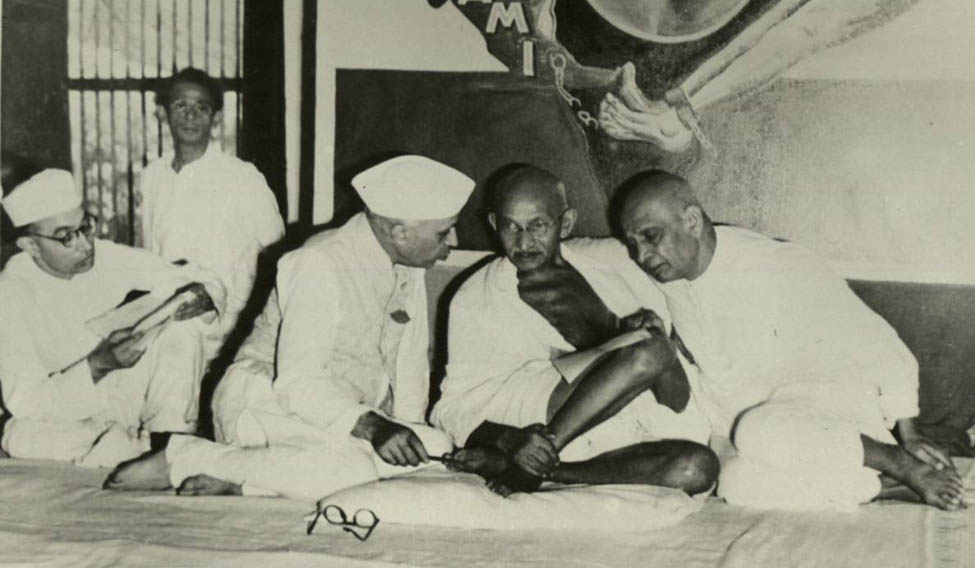

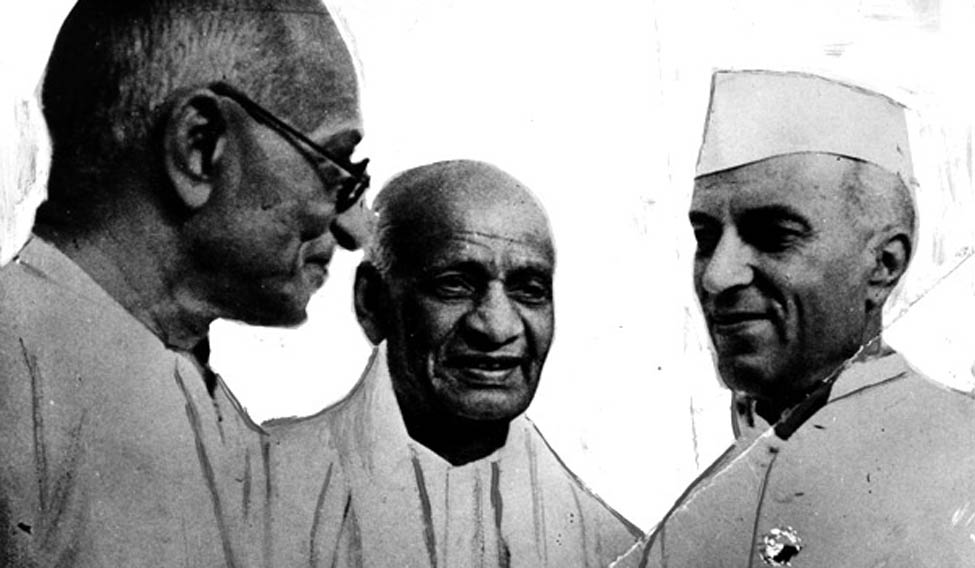

(From left to right) Mahatma Gandhi, Sardar Patel and Jawaharlal Nehru | Wikimedia Commons

(From left to right) Mahatma Gandhi, Sardar Patel and Jawaharlal Nehru | Wikimedia Commons

Gandhi had his own reasons to choose Nehru. As Sankar Ghose claims in his book, Jawaharlal Nehru, a Biography, Nehru had differed with Gandhi in theory, but followed him in action. Unlike Patel, Nehru had a greater influence on different sections of the society. Moreover, Gandhi thought the secular ideals would be safe in the hands of Nehru. “By choosing Nehru, Gandhi chose a person whose outlook on the Hindu-Muslim question, economic matters and international affairs was broader than that of Patel,” Ghose writes.

Post independence, Nehru became the prime minister and Patel his deputy. They showed a mutual bonhomie for the next couple of months, but were again headed for a break up. By December 1947, Patel was on the verge of submitting his resignation, claims Ghose in his book. Both of them shot off letters to Gandhi complaining about each other, Patel's main complaint being Nehru's intervention in his ministry.

Ghose writes that Gandhi, while fully approving Nehru's secular policy of protecting the minorities, was discontent over Patel's approach to Muslims. During the Delhi riot, a section of ministers led by Patel was opposed to giving protection to Muslims in Delhi as Hindus and Sikhs were being forcibly driven out of Pakistan. According to Ghose, when the new government refused to release the Rs 55 crore to Pakistan under the partition agreement, Gandhi, with tears in his eyes, told Patel: “You are not the Patel I knew once.”

Gandhi launched a fast on January 13, 1948 for the restoration of peace in Delhi that had witnessed a Hindu-Muslim riot. That was the first time Gandhi had launched a major fast without informing Patel, and it was also rumoured that the fast was directed against Patel's “anti-Muslim” attitude.

When the Nehru-Patel cold war reached its peak, it was expected that Gandhi would ask one of them to resign. He, however, discussed the matter with Mountbatten. This would have infuriated Patel, who had almost made up his mind to break up with Nehru. Ghose in his book quotes Patel as having told his confidants: “Nehru had lost his head, he would not stand the nonsense anymore, and that the old man (Gandhi) has gone senile. He wants Mountbatten to bring Jawahar and me together.”

Patel had a meeting with Gandhi on January 30, where the former is said to have lost his temper while talking about Nehru. Gandhi assured him that he would discuss all issues in the evening prayer meeting. But destiny had its way. On the way to the prayer ground, Gandhi was shot dead by Nathuram Godse, a Hindu fanatic.

Ghose writes: “Beside Gandhi's body, Mountbatten told them (Nehru and Patel) that Gandhi's last wish was to bring them together and keep them friends. Nehru and Patel nodded and embraced each other.”