John Reardon was about to fly to Malawi for a post-college stint with the Peace Corps when his phone rang. It was Sotheby’s senior vice president and doyenne of watches Daryn Schnipper. The auction house was recruiting personnel for its watch department, she told Reardon. Was he interested?

Reardon never made it to Malawi. In 1997, two weeks after graduating from Rhode Island’s Providence College, he started his new job working for Schnipper at Sotheby’s US headquarters on New York’s Upper East Side. Now, at age 42, Reardon is the international head of the watch department at Christie’s, the world’s biggest watch-auction house. How did he get what is, one might argue, the most important job in the vintage-watch world? What is that job like? We met with Reardon to find out.

His choice of career was due, in large part, to a happy accident: he was born and raised in Bristol, Conn., the heart of what is in effect clock country. Bristol and many nearby towns were home to a small army of 19th and 20th century clock companies—Waterbury Clock Co., Seth Thomas, E. Ingraham, Sessions and many others.

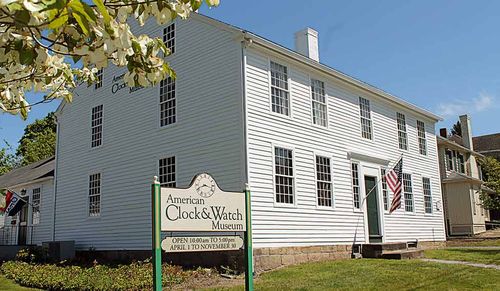

Reardon’s interest in horology stemmed from a visit to the American Clock & Watch Museum in Bristol, Conn.

Reardon’s interest in horology stemmed from a visit to the American Clock & Watch Museum in Bristol, Conn.

Bristol is also the home of the American Clock & Watch Museum. Reardon visited the museum for the first time as a teenager and met its venerable curator, Dana Blackwell. Reardon was smitten by the museum’s thousands of American-made timepieces and, under the tutelage of Blackwell and his successor, Stuart Mitchell, learned clockmaking. Throughout high school he did volunteer work for the museum. “Then I very quickly found out I could clean clocks and actually make money,” he says. He set up a workshop in the basement of his family’s house. Into it flowed a steady stream of 19th-century, Connecticut-made clocks, more than Reardon could handle. He spent as much time as possible at the bench, continuing the work all through college. He also worked for the Willard House and Clock Museum, in North Grafton, Mass., and, in a very different vein, the Providence-based Speidel, where, as an intern, he helped design watch straps.

Reardon was having a blast with his creaky old clocks, but they were just a hobby. He wanted to make a difference in the world. As he approached graduation, he signed up for the Peace Corps. But the call from Schnipper, who had heard about Reardon’s horological bent from his mentor Blackwell, was a siren’s song.

In his early days at Sotheby’s, Reardon cataloged the most famous Patek Philippe ever, the Graves Supercomplication.

In his early days at Sotheby’s, Reardon cataloged the most famous Patek Philippe ever, the Graves Supercomplication.

Reardon’s job at Sotheby’s included cataloging timepieces that would go up for auction: researching their technical features and provenance, determining their condition and estimating their prices. “I look back at it very fondly; as a cataloger you’re alone with the piece, working sometimes into the wee hours of the morning,” he recalls. In the 1990s, far less information was available online than can be found today, and researchers relied on books and, even more importantly, on watch experts. What you knew depended a lot on whom you knew, Reardon says. “You had to find the most knowledgeable people in the world to assist you. There weren’t schools to go to, so you had to find your own expertise.” Over the years, Reardon nurtured relationships with a network of watch savants such as the prominent collector Winthrop Kellogg Edey (he left 21 clocks and watches to the Frick Collection in New York when he died in 1999). “I went to see him once a week; I would show him timepieces and we would talk about them.”

The first catalog he worked on featured Rolex ephemera such as vintage store displays. His ephemera phase was, well, ephemeral. Reardon soon began cataloging watches by Patek Philippe, including the most famous Patek Philippe of all time, the Henry Graves Supercomplication, which would bring $11 million when it went on the block in December 1999. It was the most expensive timepiece ever sold at auction. (In November 2014, Sotheby’s auctioned it off again, this time for $24 million.)

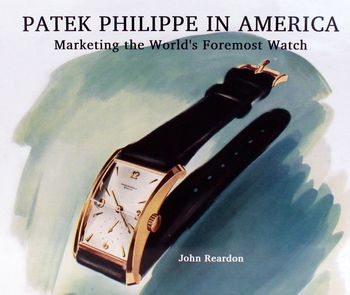

Reardon collects Patek Philippe print ads, which provided the basis for his 2008 book about the brand’s history in the U.S.

Reardon collects Patek Philippe print ads, which provided the basis for his 2008 book about the brand’s history in the U.S.

Patek Philippe became his passion. “It was really at this point that it embraced me and to this day Patek Philippe is everything for me,” he says. He likes the brand not just for its technical prowess and its fine workmanship, but for its history of tribulation, which began with Antoine Norbert de Patek’s battle to establish the company in the mid-19th century. (De Patek’s trials included one particularly vexing trip to the U.S., where his watches were almost stolen and he was stranded for days on a boat that ran aground.) He is intrigued by the fact that, until 1989, when Patek unveiled its famous Caliber 89 and auctioned it off for 4.95 million Swiss francs at a sale marking the company’s sesquicentennial, the brand was widely under-appreciated. “After 1989, it’s a different story line. Up until then, it was a constant struggle,” he says. Lastly, he likes the way Patek’s watches look, both outside and inside. “The beauty and the aesthetic really resonates with me,” he says. (Of the six wristwatches he owns – he has many American pocketwatches − four are Patek Philippes. During the interview he wears his favorite, a yellow-gold Reference 2525 from 1951.)

Such was his admiration for the brand that, in 2001, when Patek Philippe called him to ask if he were interested in working there, he at first thought it was a prank by someone aware of his obsession. “It was like a dream come true. I basically said, ‘Sign me up.’” (As it turned out, getting the job wasn’t that simple. He faced four months of interviews before he landed it.) His job at Patek was to meet with retailers all over the U.S. to balance their stocks and train their personnel on how to present Patek Philippe watches to their best advantage.

Reardon liked the job but there was one problem: he missed the world of vintage watches. To scratch his vintage-watch itch, he started to write, in his spare time, a book called Patek Philippe in America: Marketing the World’s Foremost Watch. It tells the story of the brand in this country, beginning with de Patek’s travels here and ending in the late 1980s. It does so primarily through the use of Patek Philippe advertisements, which Reardon has been buying on ebay since the 1990s. (The subtitle The World’s Foremost Watch was an advertising tagline the company used in the 1950s.)

Dial and movement of Patek Philippe’s Ethan Allen grand complication

Dial and movement of Patek Philippe’s Ethan Allen grand complication

“I started obsessively collecting every print Patek Philippe ad that came up, not just in the US but from all around the world. Now I have a collection of more than 1,000 ads,” he says. They are a treasure trove of information. “They’re the best primary source for learning about watches because the ads show pieces that are unpolished and untouched. They show the historical context in which the watches were presented, with original prices in many instances, how the watches were sold and in many cases where they were sold.” As a Patek employee, Reardon had access to its historical records. (He made the most of it. The book contains such background color as a 1930s map of the US showing the zigzag route one of the company’s salesmen followed while calling on retailers.) He also got a huge assist from former US CEO Werner Sonn, who began working for the company in 1939 and hence had unrivaled knowledge of its doings in this market. Sonn put Reardon in touch with people all over the world who gave him useful information about the brand’s history.

Christie’s US headquarters at Rockefeller Center

Christie’s US headquarters at Rockefeller Center

But the book didn’t quite quench his thirst for vintage, so after nearly a decade at Patek he returned to that world: not at an auction house but at the Betteridge jewelry store in Greenwich, Conn. His job was director of vintage and estate watches. He stayed there a year.

It was one of the hardest of his life, he says. Reardon loved fine timepieces and was in awe of the painstaking craftsmanship required to make them. He was fascinated by provenance and by history. All that was shoved into the background when he entered the nitty-gritty world of retail. “They don’t mean much when you’re trying to sell a watch,” he says. “A lot of the romance of watches was put aside for me. It was about the reality of the business.”

To find watches to sell, he traveled to shows around the country organized by the International Watch and Jewelry Guild. “They’re the Wild West of timepieces,” Reardon says of the shows. Thousands of vintage watches are laid out on exhibitors’ tables, which are arranged row after row in a giant open room. “It’s the unregulated commodity trading floor of the industry. There is zero romance. Nothing matters except the dollars and the watches and the only thing that separates you from the rest is knowledge,” he says. “It was the school of hard knocks to work the show circuit. There’s nothing glamorous about it.”

For all that, he’s glad he got to see the vintage-watch scene from another vantage point. “It was fascinating to see how this part of the industry works, … where supply and demand are everything.” And cruising the aisles at the IWJG shows did yield some gratifying surprises. “You still have the moment when you find some extraordinary piece, or when you find a watch you’ve been looking for, or learn something you’ve never known before. That’s why we all do this.” The “adrenaline-powered treasure hunt,” as he calls it, is what it’s all about.

Surprise star: the Pearl of Bahrain sold for $437,000 in December 2015. Its estimate was $10,000 to $15,000.

Surprise star: the Pearl of Bahrain sold for $437,000 in December 2015. Its estimate was $10,000 to $15,000.

In 2011, sotheby’s asked him to return, as the head of its watch department in the U.S. He stayed for nearly two years. His knowledge of the watch industry was much broader than it had been when he left, he says, thanks to his time at Patek Philippe and at Betteridge. “With that knowledge and those relationships, I was able to have a very successful time, my second time at Sotheby’s.”

Rival Christie’s took note: it hired him in 2013 as head of its watch department in New York. The following three years were a roller coaster ride, Reardon says. First came the resignation of his boss, Aurel Bacs, international head of watches. Bacs is a star in the watch-auction world: it was under him that Christie’s had become the world leader in watch sales. Its watch sales rose from $8 million to $126 million in the decade Bacs was there. His departure to form a consulting company, Bacs & Russo, with his wife, Livia Russo, also a watch specialist at Christie’s, rocked the watch-auction world. (Bacs and Russo have an agreement with the Phillips auction house to work for its newly re-established watch department.)

Then, in late 2013, in the wake of Bacs’s departure, came Christie’s appointment of Reardon and Sam Hines, the auction house’s watch chief in Hong Kong, as international co-heads for the watch department. In 2015, Hines moved to Phillips, as international head of watches. (Unlike Bacs and Russo, who are outside consultants, Hines is employed directly by Phillips.)

After Hines left, Reardon found himself alone in the top job. “At that point, I inherited something I didn’t expect, the helm of the world’s number one auction house,” he says.

As helmsman, he manages a staff of 20 watch specialists in New York, Hong Kong, Geneva and Dubai and oversees Christie’s eight annual live watch auctions and its online auctions (there were also eight of these this year). Reardon is an enthusiastic proponent of online auctions, which vastly broaden the number of potential buyers. And because there are no space limitations in online catalogs, as there are in print ones, the auction house can present more information and photos. This increases buyers’ confidence, Reardon believes. “We’re starting to see with our digital sales, prices that are higher than what we see with our [print] catalog,” he says. The future will be completely digital.”

Lastly, Reardon is in charge of private sales, of which there are two types. In one, a customer contacts Christie’s requesting a particular watch, and Reardon or another watch specialist finds it for him. In the other, handled through Christie’s Watch Shop, Christie’s posts watches for sale with fixed prices. Private sales are the fastest growing category of sales for the watch department, Reardon says. (He won’t divulge Christie’s watch department sales or the respective portions provided by live auctions, online auctions and private sales.)

His favorite part of the job is still the hunt, especially for what he calls “hero” lots around which he can build a sale. (Reardon isn’t an auctioneer; he leaves that to Thomas Perazzi, Christie’s head of watches in Geneva.) Each morning he clicks through the fresh crop of e-mails that has sprouted up in his in box since the day before. “You see things worth a few hundred dollars, and then you come to something worth half a million dollars. That’s when we jump on a plane and go to see the person to discuss it.” He also does estate appraisals, picking through the contents of safe deposit boxes. Sometimes the boxes yield amazing surprises: extremely valuable watches, in mint condition, that he didn’t even know existed. “After we do our research and see the archives we find out that yes, it’s the real deal. These discoveries make everyone in the office cheer.”

Thanks to his stint at Patek Philippe, he has a wish list of Patek pieces he would love to get his hands on. “I had the opportunity to see a lot of great pieces, ones that had been handed down from generation to generation. Many of these pieces will not come to market. But just knowing they exist, really unique references with really unique retail signatures, in unbelievable condition … it’s fun knowing they’re out there,” he says. “And sometimes conditions change. Prices can reach a level that makes it easier to part with Grandpa’s watch.”

Once in a while a hero lot walks right through his door. “I love it when people come in and say, ‘I have my great-grandfather’s watch. It has all these buttons on it. We don’t know what it does.’ And your eyes light up.”

One fantastically valuable watch that just “walked in the door,” so to speak (actually, the consignor phoned about it) was last December’s Pearl of Bahrain, a Patek Philippe time-only Reference 2573 wristwatch made in 1958. The watch gets its name from the tiny natural seed pearls that serve as hour markers, believed to have been harvested off the coast of Bahrain. It was a gift from a Bahraini emir to an American businessman. Neither its consignor nor Christie’s had expected much of it: the watch had a presale estimate of $10,000 to $15,000. It brought $437,000 following a scene of manic bidding in which the saleroom’s phone banks were busier than Reardon had ever seen them. “It could have been an Impressionist or contemporary art sale,” he says. The fact that the watch was fresh to market, very rare (Christie’s research suggests it is the only extant Patek Philippe with the original pearls), in mint condition and a symbol of a friendship between a Middle Eastern royal and an American, captured bidders’ imaginations, Reardon says.

The real heart-stopping finds are watches with unusual, or, better yet, one-of-a-kind features linked to interesting provenance and technical distinction. One such watch is a 1903-’04 Patek Philippe pocketwatch that Christie’s auctioned in December. It’s a grand complication, with split-seconds chronograph, minute repeater and perpetual calendar. The watch was commissioned by a Louisiana woman named Carrie Belle Carter as a gift for her husband, a homeopath named Ethan George Allen. Allen had gotten rich selling herbal medicines. That’s the key to the watch’s most obviously unorthodox feature: seven of the watch’s hour markers are designed with a botanical motif, with plant roots spelling out “Allen” and forming the initials “C.B.C.” The watch’s movement is inscribed with the names of both Carrie Belle Carter and Patek Philippe. Reardon had for years heard rumors of the watch’s existence; they were confirmed when he saw it for himself (he won’t say where).

Story Time

Reardon is a history buff and lover of watch stories. No wonder he thinks a collector’s watches should tell a tale. He champions what he calls a “vertical” approach to collecting, in which the collector buys watches around a particular theme with the intent of painting as complete a picture of it as possible. Do it right, and you will have what amounts to a “wearable museum,” he says.

If your theme is, for instance, Patek Philippe perpetual calendar chronographs, you would start with Reference 1518. “Then you go to the 2499 and through the various series and then you get all the way to the modern production equivalent. This enables a collector to tell the history in a way they would not be able to do if they just collected 1518s. It’s a way to show the evolution of the design and the technical evolution from caliber to caliber. And it allows collectors to have pieces they can wear along with the pieces they leave locked away.”

The important part, he says, is knowing where you’re going and creating a road map to get there. Don’t rush, he says. “Part of it is being patient and being ready to pounce when you find the right watch. I think I spend more time telling collectors not to buy watches than to buy them,” he says.

Whatever you do, he says, don’t collect as an investment. “This is not a good idea,” Reardon says. When a potential collector tells him he wants to collect watches to make money, he tells them, “Get a mutual fund instead.” His warning to them: any novice who thinks he can game the vintage-watch market is bound to lose.

For more stories visit WatchTime India