It was my wife's uncle, T.V. Narayanan (Baby mama), who first alerted me to the story. At his home in Bengaluru, he pulled out a faded newspaper cutting with a dateline 8 December, 1892, which stated that Swami Vivekananda had spent the night at the house of a prominent lawyer T.A. Doraiswamy Iyer. “You know,” said Baby mama proudly, “Doraiswamy Iyer was my grandfather.” I resolved that some day I would chronicle this story, for I had heard that Doraiswamy, in addition to being an eminent lawyer, was also a famed musician who had performed at the court of the Maharaja of Cochin. His legal acumen matched his musical genius. He gave classes in music, which were as sought after as his legal advice.

As is well known, Vivekananda undertook a padayatra through the country between 1888 and 1893 to understand the 'soul of India'. He travelled like a wandering monk, completely bereft of material ties. He had among his possessions a kamandalu (water pot), and the books Bhagavad Gita and The Imitation of Christ. Having completed his journey in the north, Vivekananda found himself in Mysore as a guest of the Diwan K. Seshadri Iyer in late 1892. The Diwan arranged for an audience with the Maharaja of Mysore and the latter was very impressed with young Narendra's erudition and eloquence. Vivekananda was travelling as Narendranath―though initiated as a monk by Shri Ramakrishna, he had not yet become a swami. He informed the Maharaja that he had been invited to attend the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago the following year as a delegate. In a way, his padayatra through India was to prepare him for his address in Chicago. The padayatra was also a resolve he had made to Ramakrishna Paramahamsa that he would try and know India better.

The young Narendra was one of Ramakrishna's favourite disciples. Initially a skeptic, he was completely fascinated and converted by Ramakrishna's deep spiritualism. At Mysore, he heard about the deep-rooted caste prejudices and the practice of untouchability in Kerala from other religious leaders. Though caste practices were entrenched in other parts of India that he visited, Vivekananda felt it was a bit extreme in Kerala; he even called it a 'lunatic asylum'. He thought people were mad to practice such kind of discrimination against their fellow men. Vivekananda wanted to observe the social practices in Kerala for himself, but it was not in his itinerary. The Maharaja of Mysore, Chamaraja Wodeyar, solved the dilemma by offering him a railway ticket and a letter of introduction to the Diwan of Cochin. Vivekananda, who had earlier turned down the Maharaja's offer of a ticket to Chicago, accepted.

There are enough accounts of Vivekananda's travels through Kerala. He travelled via Thrissur, Kodungallur, Tripunithura and Ernakulam, moving on to Thiruvananthapuram, Nagercoil and Kanyakumari. At Kanyakumari, no boatman was willing to row him across a turbulent sea to a rocky outcrop and Vivekananda jumped into the sea and swam across. The rest as they say, is history. His three day meditation on the outcrop eventually became the Vivekananda Memorial, which now draws visitors from across the world.

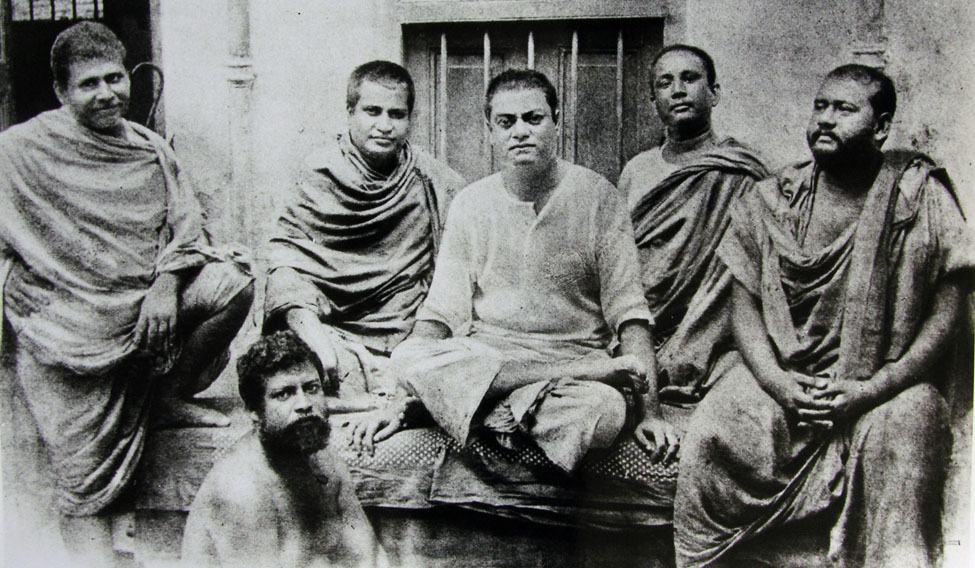

Lawyer and musician Doraiswamy Iyer | courtesy Sridhar Balan

Lawyer and musician Doraiswamy Iyer | courtesy Sridhar Balan

He, along with a handful of followers, found themselves in Ernakulam town on the evening of December 7, 1892. They heard melodious music coming from a house they were passing by. Vivekananda listened, entranced. When he inquired about it to a passerby, it was revealed that the house belonged to a prominent lawyer Doraiswamy Iyer. Who was he? A family account states that he was the son of Appu Bhagvathar, a musician. The same family account states that Bhagvathar died without much wealth, except for a house in Tripunithura, but he had left Doraiswamy a musical legacy. So, Iyer, who was born in 1860, started life as a musician at the age of 12, and nursed a passion for music till he passed away in 1921. He had formal schooling only up to the First Form, but through diligence and hard work, he passed the Pleadership Examination and enrolled in the Bar as a lawyer. His legal practice grew, and he became a prominent member of the Bar. His fame and prosperity grew, but Doraiswamy never forgot his humble origins.

The same family account states that his house 'Saraswati Vilas' was always open. There was always an endless stream of visitors, and one never knew who was passing through or staying. In addition to the numerous support staff, the house always had a stream of legal clients. Disciples would come for music lessons and certificates that would enable them to get jobs as music teachers. Fellow musicians and bhagavathars in town for a concert were warmly welcomed. There were no prominent hotels then, but they would all stay at Saraswati Vilas. Every Saturday at 10am, a large number of women and children from the lowest caste groupings called ullatas, living in the outskirts of the town, would gather by the front verandah. They would be given a traditional offering of oil, followed by rice. Though sometimes the gathering would be unusually large, there would be no jostling or shoving, for they were confident that none among them would be turned away empty-handed.

Doraiswamy was more popularly known in family circles as 'Ooty Appa' due to his annual sojourn in Ooty every summer. It is not known whether he had a house in Ooty or if he merely hired a residence. But nothing distracted 'Ooty Appa' from his music. He was gifted with a rich voice and excelled in the pallavi, with his own improvisations. For his prowess in music, the Maharaja of Cochin presented him with the veera sringala. The gold bangle that marked this distinction was in the family for a number of years. Such was the man whose music stopped Vivekananda and his followers. And what was Doraiswamy singing? He was rendering the Ashtapadi, the immortal composition by the legendary 12th century composer Jayadeva. Jayadeva was an ardent devotee of Krishna. The entire Gita Govinda is in Krishna's praise. The 24 verses of Ashtapadi tell us the story of Radha and Krishna, of love and disappointment, and finally reconciliation and unity. The Ashtapadi is set in eight padas or beats and legend has it that when the great Jayadeva composed it, his wife Padmavati danced to the rhythm. The Ashtapadi has been sung by a number of musicians and both Balamurali Krishna and O.S. Arun have excelled in it. But it was Doraiswamy Iyer who sang it in his inimitable voice that evening. Needless to say, Vivekananda was entranced. Vivekananda was trained in Dhrupad (Hindustani classical) at Ramakrishna's behest and he was a competent pakhavaj player.

After the song ended, Vivekananda entered the house along with his followers. Doraiswamy was visibly startled to see the young yogi. He was even more astounded to hear that Vivekananda wanted him to sing some more! Apparently, Vivekananda too joined the lawyer in performing the Bengali ragas. After the impromptu concert, Doraiswamy requested Vivekananda to stay the night. The next morning, Vivekananda and his entourage went their way. This encounter was apparently widely reported in the Malayalam newspapers of the time. We now also have a mention of this encounter in Shyamali Chowdhury's account of Vivekananda's travels in India. In her account of the travels, now available in published form, Chowdhury records that Vivekananda spent a night at the house of a prominent lawyer Doraiswamy Iyer in Ernakulam, who sang the Ashtapadi. We also have an account of Swami Ramakrishnananda, also a direct disciple of Ramakrishna, visiting Doraiswamy. At the house, the swami told Doraiswamy that his house was now a tirthasthan (holy place). He then traversed all the places where Vivekananda had stood—sitting, sleeping and prostrating at each.

On a visit to Kolkata, I was taken to the Ramakrishna Boy's Home School in Rahara. This had originally started as an orphanage in 1944, but now a full-fledged high school. I was working with the prominent school publisher Ratna Sagar of Delhi then. My Kolkata colleague felt that my visit would help grow the school business and since I spoke Bengali fluently, communication would not be a problem; the headmaster spoke only in that language. The only problem was that he was a monk, more keen on spiritual matters, and would spare only five minutes for a visitor. Undeterred, I entered along with an increasingly nervous colleague and thought I would narrate the Vivekananda story as an ice-breaker. The swami was all attention, and listened intently. After I finished, he was incredulous and wanted to know how I knew all this. Surely, I could not be that old! He relaxed when I told him that Doraiswamy was my wife's great-grandfather. He then proceeded to add a postscript. For years, he said, after Swami Ramakrishnananda paid his respects at Saraswati Vilas, the house had become a pilgrimage spot, a tirthasthan for all monks of Ramakrishna Mission visiting Kerala on their way to Kanyakumari. He asked me whatever had happened to the house and I told him it had been demolished a long while ago. We spent an enjoyable 45 minutes together but regrettably, I still don't know whether we got any business in the school!